Workshopping Edinburgh

By Minou Arjomand

The theme of the Edinburgh International

Festival this year was "Oceans Apart": an exploration of relationships

between the Old World and the New. I travelled to Edinburgh as

the New World's sole delegate at a workshop program held parallel

with the festival. This workshop was part of the Deutsche Bank

Foundation's "Akademie Musiktheater Heute," a two-year series

of workshops for young professionals in opera (composers, directors,

conductors, dramaturgs, set designers, and--as the Germans call

them--Kulturmanagers). An American, I was there as a

dramaturg. All of the other fellows lived in German-speaking European

countries; most were born in Germany.

Shuttling back and forth to various workshops

over the past few years, it has struck me that the salient differences

across the Atlantic weren't so much in the theater itself, but

in how people talk about and evaluate theater. One difference

was brilliantly articulated by the conductor Pinchas Steinberg

during a workshop at the Teatro Real in Madrid this June. Referring

to musicians, Steinberg said that in his 40 years of experience

there had been one major difference between American and European

orchestras. When American instrumentalists encounter a passage

they have difficulty playing, they always play softer. When Europeans

do, they play as loudly as they can. The observation runs counter

to the stereotype of American brashness and volume, yet it was

borne out for me in all of our workshop sessions.

During many of our discussions, the level

of vitriol and frequency of interruptions were on par with Tea

Party town halls, even though the stakes of the arguments often

seemed petty. This hostility may have come in part from the rigidly

hierarchical structures of German opera houses, perhaps in part

from the doom that tended to hover over our conversations about

the future of opera with German directors. When I applied to the

program, I was asked to write an essay about how to save opera

from its current "crisis" (the nature of the crisis was unspecified).

After we saw his production of Samuel Beckett and Morton Feldman's

opera Neither, Peter Mussbach told us: "I really don't

know what your generation is going to be able to do that hasn't

already been done: in a sense, I think that my production of Neither

really shows that we have come to the end of new possibilities

for theater."

On our first full day in Edinburgh we met

with Jonathan Mills, current director of the Edinburgh International

Festival. Mills immediately launched into a well-rehearsed presentation

of his interests in risk-taking and creative innovation. Along

the way he mentioned that his current thinking about the social

role of art was influenced by reading a book about neuroscience.

At this, a round-faced German dramaturg wearing a lavender and

green striped tie and a violet v-neck sweater interrupted him

mid-sentence: "You say that you are interested in taking

risks. Yet now you mention that you have been reading a book about

neuroscience."

The dramaturg, paused, scoffed, and paused

again as though to drive his jibe home, "And yeah, this sort of

positivist thinking, and especially neuroscience is very trendy

right now. But obviously we can all agree that it represents a

reactionary position, and not a very risky one. So, my question

would be that I'd like to hear more about your programming choices

and how they reflect risk."

He leaned back in his chair, manifestly

pleased with himself. Although Mills seemed as mystified about

the substance of the dramaturg's complaint as the rest of us,

the timbre of the comment left no doubt that it was intended as

a crippling insult. A quick hair sweep to the right, and Jonathan

Mills countered that programming a John Adams opera as the festival's

opening number was very risky indeed, and began to talk about

the project.

The dramaturg interrupted again: "Oh yeah,

the Christmas Oratorio, right?" Smirk.

"No." To be fair to the dramaturg,

it was, in fact, a Christmas Oratorio: El Niño, billed

in the program as giving "new life" to "the miracle of the nativity."

I was stunned when later that day, the same dramaturg remarked

to me that he was impressed by Mills and found his presentation

pretty convincing, on the whole. I couldn't imagine how the dramaturg

would address someone he didn't respect.

***

In Ill Fares the Land, Tony Judt

argues that we have forgotten how to ask questions. In the political

arena we no longer ask whether our actions are just, we ask for

the capital risk involved; we don't ask what a good society entails,

we ask about profit margins.

Something is profoundly wrong with the

way we live today … We know what things cost but have no idea

what they are worth. We no longer ask of a judicial ruling or

a legislative act: Is it good? Is it fair? Is it just? Is it

right? Will it help bring about a better society or a better

world? Those used to be the political questions, even if they

invited no easy answers. We must learn once again to pose them.

During our workshops, I grew discouraged

about our ability to ask questions about theater as well. Rather

than asking if the theater makes us and our societies better,

we Deutsche Bank fellows would ask: Is it new? Is it radical?

Does it look like it was produced without the intention of being

a commercial success? To his credit, Jonathan Mills did begin

our workshop by throwing out some of the right questions for a

festival director: What is a festival? How does it relate to its

social context? What does it mean to the community of audience-members?

But he raised all of these questions rhetorically. And once he

brought up risk, he had a difficult time trying to turn the conversation

away from risk as the sine qua non of respectable programming.

Part of the reason that questions about

social good were almost entirely absent from our hours of discussion

about contemporary theater may be that it was taken for granted.

State sponsorship of art has never been seriously questioned in

the countries where most of the fellows study and work. While

the public support of art in Germany would be a dream to many

of us in the States, it may also lead to a certain complacency

on the part of young artists who are not called upon to justify

their work in social terms. At the same time, it is hard to speculate

about what a parallel program with American fellows would be like:

avant-garde opera practice is hardly among the priorities of government

spending or corporate philanthropy in the United States.

In some ways, the twin theater festivals

in Edinburgh represent the funding models from each side of the

Atlantic. The Edinburgh International Festival and the Edinburgh

Fringe Festival were both born in 1947, when the homes of Europe's

other major festivals--Munich, Salzburg, Bayreuth--fallowed in

moral as well as physical decay. These former sites of European

artistic pilgrimage had spent a decade as vehicles for Nazi propaganda.

Half a century after the cities were rebuilt, the festivals haven't

recovered from their pasts. Hans Neuenfels's famous production

of Die Fledermaus at Salzburg sent its 200 euro-a-seat

paying audience into a tizzy by portraying them on stage as cocaine-snorting

Nazis. In the 2007 Bayreuth festival, Wagner's great-granddaughter

Katharine Wagner staged Hitler's favorite, Die Meistersinger.

The only coherent remarks most reviewers found to make were that

it was trying to say something about Hitler, and that

it got a lot of boos. Since assuming leadership of the Bayreuth

Festival, Katharine Wagner has asked academics to investigate

Bayreuth's ties to the Nazis, in particular the rumor that her

grandmother was Hitler's lover.

Free from this sort of compromised history,

Edinburgh offers a reprieve from the naval-gazing of much Teutonic

Regietheater. The International Festival in Scotland's city on

a hill was created to promote peace through a celebration of culture.

It was the first major transnational institution in postwar Europe

designed specifically to forge a collective European identity.

At the same time, the International Festival was hardly designed

as a democratic institution: it was traditionally led by a single

director who saw himself as the arbiter of European taste.

In contrast to the International Festival,

the Fringe is organized on the model of free-market anarchy. The

Fringe began when several theater companies arrived at the first

International Festival uninvited, and produced their shows simultaneously

with the official program. In the following years, more groups

followed their example, and in 1959 they created the Festival

Fringe Society. This Society has never instituted a selection

process. Any group who can pay for its transportation to the festival,

accommodations, production costs, the 250-pound registration fee,

and rent its own venue in Edinburgh, is welcome.

The International Festival is sometimes

accused of snobbery and importing experimental high budget productions

that have little to do with Scottish culture; the Fringe Festival

is sometimes accused of rabid commercialism and too much standup

comedy. Not that the International Festival isn't a commercial

venture itself: like other summer festivals around Europe it was

in part designed to increase tourism, and its role became increasingly

important as Scotland shifted from an industrial to a tourist-driven

economy in the late 20th century. Its success led to a proliferation

of Edinburgh festivals during the month of August, including the

Book Festival, Jazz Festival, Military Tattoo Festival, International

Television Festival, and the Festival of Politics.

***

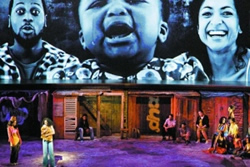

Based on the shows that I saw during my

week in Edinburgh, it seems that the difference between the two

festivals is mostly one of scale. On our first night, we fellows

attended Porgy and Bess, co-produced by the Edinburgh

Festival and the Opera Lyon. Under William Eddins' leadership,

the orchestra sounded wonderful: he managed to keep Gershwin's

harmonic fineries from drowning in the brass section. The staging

departed from the usual period productions of this opera and introduced

dancers and a large video screen. The dancers, video, and staged

actions were often redundant. In the storm scene (from top down),

the screen showed a video of crashing waves, singers braced themselves

and sang about the crashing waves, dancers emulated waves. Often

the video used a green screen to simultaneously project exactly

what was happening on stage above the stage, except that the projection

included some close-ups and period details of Catfish Row.

After

his death, Gershwin's estate stipulated that Porgy and Bess

could only be performed by an all-black cast. Gershwin had been

offered a commission by the Metropolitan Opera but turned it down

in order to write Porgy and Bess (it wasn't until 1955,

twenty years after its premiere, that a black singer first appeared

at the Met). While the opera did support the careers of the first

generation of African-American opera singers, Porgy's

folksy depiction of a rural black community is rife with racial

stereotypes. Most productions of it are far more conservative

than standard productions of Mozart or Verdi. The assumption remains

that only black opera singers can portray the happy, simple people

of Catfish Row.

After

his death, Gershwin's estate stipulated that Porgy and Bess

could only be performed by an all-black cast. Gershwin had been

offered a commission by the Metropolitan Opera but turned it down

in order to write Porgy and Bess (it wasn't until 1955,

twenty years after its premiere, that a black singer first appeared

at the Met). While the opera did support the careers of the first

generation of African-American opera singers, Porgy's

folksy depiction of a rural black community is rife with racial

stereotypes. Most productions of it are far more conservative

than standard productions of Mozart or Verdi. The assumption remains

that only black opera singers can portray the happy, simple people

of Catfish Row.

The choreographers who staged this production--José

Montalvo and Dominique Hervieu--seemed obsessed with visual authenticity.

They managed to throw in every possible visual marker of blackness:

costumes and choreography from Kris Kross music videos; brightly

colored graffiti tags on wooden fishing shanties from South Carolina

c. 1915; video clips of Martin Luther King Jr., civil rights marches,

and a burning car. Despite this preoccupation with signifying

blackness visually, though, the directors failed to convey Gershwin's

most obvious nod to historical and racial specificity: the dialect.

Aside from the few Americans in the cast, the accents were very

poorly done, as though the directors just assumed that being black

(whether French, British, or American) were enough to be able

to convincingly speak in the antiquated dialect of Gershwin's

libretto. No one else in the all-white audience seemed to notice

the incongruity. The location, era, and political message were

jumbled, but one thing was clear: these were black people. Porgy

and Bess was the biggest commercial success of the International

Festival.

Do we look like Refugees? by Beyond

Borders Productions Ltd. at the Fringe explored themes similar

to those of Porgy and Bess: how communities cope with

adversity, and what images, dialects, and intonations of voice

can convey individual experience across cultures. Director Alecky

Blythe recorded a series of interviews with refugees who lost

their homes in the 2008 Russian-Georgian War. Rather than transcribe

the interviews, Blythe gave each actor an audio recording. The

actors learned their lines by listening to the recordings, imitating

not only the words but the inflections of the voices (one of the

pleasures of this production was hearing Georgian … thankfully

with supertitles). The interviews themselves were well edited

and compiled, and had some amazing lines.

When you leave a house empty for more

than two years it goes cold. There is a Georgian curse, we say:

"May your house go cold." It becomes like an orphan

child with sad ears.

The gallows humor of the play made it a

pleasure to watch. One woman tells the interviewer that in the

refugee camps there are always weddings and new babies: "Even

couples who couldn't get pregnant before are having children.

It

seems that God is regulating the demographic situation." Blythe's

decision to have her actors not only learn from the headphones

but also use them on stage created the tension between source

material and performance, artifice and authenticity that was missing

from Porgy and Bess. Despite the closeness of speech

to the original interviews, the headphones emphasized the Brechtian

distance between the actors and the people they were portraying.

It

seems that God is regulating the demographic situation." Blythe's

decision to have her actors not only learn from the headphones

but also use them on stage created the tension between source

material and performance, artifice and authenticity that was missing

from Porgy and Bess. Despite the closeness of speech

to the original interviews, the headphones emphasized the Brechtian

distance between the actors and the people they were portraying.

While Do We Look Like Refugees?

included a great deal of cultural specificity, it did not claim

to portray the souls of the people. In one episode, the interviewee

briefly speaks in mundane terms about her work. Then she asks

the interviewer what the interview is for, finds out that it is

for a theater piece that will play for international audiences,

and begins to pontificate on the beauty of Georgia and cite national

poets in elevated terms. At the same time as Blythe and her actors

explore Georgian identity, they also show how contingent this

identity is on political ambitions and circumstances.

***

Organizing each year's programming around

a theme has been one of Mills's innovations to the festival, and

it is linked to his desire to broaden the Festival's traditional

focus on European theater. In an interview with Simon Thompson

for Musicweb International, Mills explained:

While I have attempted to argue that

this Festival need not be so Eurocentric, I haven't attempted

to do so in a nationalistic way by saying, for example, "This

year we're focusing on China, next year on Iceland or Romania."

Instead I've tried to construct a more multi-faceted approach

to the theme underpinning each festival journey. This year I've

said that I'm interested in looking at a particular region,

not a single country, and an idea of how that relationship between

worlds might express itself from both positions.

This position is compelling--I only found

myself wishing that the theme were more clearly articulated: had

Mills not told us about the theme during our discussion, I wouldn't

have realized there was one.

There was no headline about the theme in

the festival program. Instead, it appeared in 12-point font in

Mills's brief introductory text. He wrote that the motto "Oceans

Apart" conjured "images of the harsh physical journeys across

huge expanses of sea, taken at great peril by European explorers

from the 14th century, in search of new worlds. They also suggest

the often brutal suppression wrought by colonial invasion. But

most of all, I hope that they suggest an expansive imaginative

territory between places of extraordinary cultural diversity which

this programme seeks to explore and even to bridge." This text

throws a sentence of victimhood to both the oppressors and oppressed,

but trumps any historical or political specificity with a blanket

celebration of hybridity. I was a bit thrown off when during our

workshop Mills told us that "as a former colonial himself " he

felt comfortable confronting issues that perhaps his British counterparts

might avoid. If the Festival Director didn't recognize the difference

between a contemporary white Australian and the victims of 14th-century

colonialism, it boded poorly for the Festival. None of the descriptions

of individual productions in the program referenced the overarching

theme, and the criteria for the selections seemed to be simply

that the artists came from a historically colonized and/or colonizing

country. In other words, the theme of the Edinburgh International

Festival was simply that it was international.

I do think that the program was a good-faith

attempt on the part of Mills to promote conversation about social

and political issues among audience members. The Festival did

include a short series of panels and lectures, some of which were

about colonialism. But these events weren't free for people who

had seen the performances (they cost £6.50--more than most Fringe

shows), so audience members had to buy tickets to two separate

events to get both the art and the social dialogue. One could

certainly sympathize with the difficulty of combining a narrowly

defined theme with high-quality programming in such a large festival.

At the same time, claiming to the media (and indeed, to workshop

participants skeptical of your subversive cred) that the festival

tackled a political theme like colonialism when it actually presented

an apolitical mix of multicultural fare was irresponsible.

Of

the productions, one of the few explicitly about colonialism was

the 18th-century opera Montezuma composed by Carl Heinrich

Graun to a libretto by his benefactor, Friedrich II of Prussia.

The Enlightened monarch felt sympathy for the Aztecs--or at least

antipathy toward the conquistadors--and began his libretto with

expositions of Montezuma's justice and enlightenment. Montezuma

is too trusting, though; he is tricked by Cortés and dies in the

final act.

Of

the productions, one of the few explicitly about colonialism was

the 18th-century opera Montezuma composed by Carl Heinrich

Graun to a libretto by his benefactor, Friedrich II of Prussia.

The Enlightened monarch felt sympathy for the Aztecs--or at least

antipathy toward the conquistadors--and began his libretto with

expositions of Montezuma's justice and enlightenment. Montezuma

is too trusting, though; he is tricked by Cortés and dies in the

final act.

Director Claudio Valdés Kuri staged the

first half of the opera as an ironic presentation of how the West

viewed the Aztecs: before the opera began, vendors with tourist

trinkets advertized their wares to the audience. During the opera,

the Aztecs dressed savage-kitsch. Montezuma sang half naked throughout,

though at one point--for no discernable reason--put on a tourist

T-shirt, removing it several minutes later. It was unclear whether

the technical problems with the staging were also meant ironically.

I think not. When the first conquistador, Captain Narvès, appeared

on stage, he brought with him a German Sheppard, who barked whenever

Narvès sang to show the captain's ferocity. Rather than barking

at Montezuma, though, the dog stared down into the pit (from my

angle, at the crotch of an extremely uncomfortable-looking bassist),

where a stage hand was obviously waving something to make him

bark. During one scene, the natives had built up pyramids with

jenga blocks. To symbolize the destruction of the civilization,

Narvès threw a plastic Coca-cola bottle at the fragile pyramids.

The bottle fell just short, hit the ground, and bounced over the

pyramids leaving them unscathed. Montezuma sang the last act on

top of a column with a very obvious safety harness around him.

When he flung himself from the top, the whirring of the harness

as it gently deposited him on the ground out-hummed the music.

Even when there weren't technical problems,

the opera was difficult to watch. Narvès appeared in the second

half with a sack full of Coke bottles. As the Aztecs ambled in

a circle with water bottles between their legs, the conquistador

assaulted them one by one and replaced the water bottles with

Coke as the natives mimed castration. As in Porgy and Bess,

overdetermination was the name of the game. Towards the end, there

was one compelling moment, when the music stopped and the conductor

Gabriel Garrido handed out new music to the singers, connecting

the missionary work of imperial Spain with the Western classical

tradition. This reprieve from the general tastelessness of the

production, however, couldn't do much to redeem it. During the

curtain call the German dramaturg fellow, who was now wearing

a dark purple tie with a light purple sweater, turned to me: "Now

that was Eurotrash."

If

the political shallowness of the staging was irritating, the treatment

of the female lead was infuriating. During Lourdes Ambriz's first

aria as Eupoforice, she was stripped and left in a ridiculous

bodysuit with uneven pom-poms over her nipples and a blindfold

over her eyes. As she sang, she shakily made her way along a narrow

catwalk between the orchestra and audience in 5-inch heels (a

symbol of Western oppression). She sang a later aria lying upside

down on a staircase, slowly moving up the steps as she sang. This

was far from the first production I've seen where the director

exploits women on stage under the pretense of showing the audience

how women are exploited in society; Catalonian director Calixto

Bieito has made a career of it. While singers often have no choice

but to follow their directors or risk their careers, it is unfortunate

that festivals and opera houses condone this sort of misogyny

and even think of it as edgy and politically progressive.

If

the political shallowness of the staging was irritating, the treatment

of the female lead was infuriating. During Lourdes Ambriz's first

aria as Eupoforice, she was stripped and left in a ridiculous

bodysuit with uneven pom-poms over her nipples and a blindfold

over her eyes. As she sang, she shakily made her way along a narrow

catwalk between the orchestra and audience in 5-inch heels (a

symbol of Western oppression). She sang a later aria lying upside

down on a staircase, slowly moving up the steps as she sang. This

was far from the first production I've seen where the director

exploits women on stage under the pretense of showing the audience

how women are exploited in society; Catalonian director Calixto

Bieito has made a career of it. While singers often have no choice

but to follow their directors or risk their careers, it is unfortunate

that festivals and opera houses condone this sort of misogyny

and even think of it as edgy and politically progressive.

Although I have never seen an effective

ironic staging of an opera (I have seen many attempted), I can

understand why the director decided on a tongue-in-cheek production

of Montezuma. I sympathize that we can't represent the

Aztecs on an opera stage without borrowing colonialist clichés,

as well as with the decision to prevent the audience from feeling

comfortable in their position as spectators. Comfort and knowing

condescension can certainly go hand in hand in productions hyped

for their multiculturalism. But there are better ways to confront

audiences than tacky costumes and a countertenor flapping his

penis around the stage.

Tempest: Without a Body was not

an opera, but it was far more effective in its negotiation between

colonial assumptions and indigenous tradition. Choreographer Lemi

Ponifasio named his company Mau after the Samoan independence

movement, and has designed it as a transnational institution bringing

together the performance practices and political activism of Pacific

peoples. The group has toured extensively and its production Requiem

was performed at the Lincoln Center Festival in 2008. Tempest

presents elements of Shakespeare's play alongside the biography

of Maori activist Tame Iti, who appears in the production. Tempest's reference points are diffuse and often abstract:

Maori struggles, post-9/11 insecurity and attacks on civil rights,

as well as Giogio Agamben's notion of homo sacre (an

individual expelled from social life) and Paul Klee's angelus

novus, all within a stark postlapsarian landscape. The production

began without warning--the noise of an explosion, incredibly loud,

while the lights were still on. A woman with tattered clothing

and small, inadequate, wings walked to edge of the stage and screamed.

It didn't sound like a stage scream. She repeated the scream.

The sound design through many parts was painfully loud. I can't

remember the last time a piece of theater hit me with visceral

fear: probably an elementary school trip to Madison "Scare" Garden.

Many of the other workshop participants concurred, and one added,

"I felt like I was present at something, that I wasn't actually

allowed to see."

Tempest's reference points are diffuse and often abstract:

Maori struggles, post-9/11 insecurity and attacks on civil rights,

as well as Giogio Agamben's notion of homo sacre (an

individual expelled from social life) and Paul Klee's angelus

novus, all within a stark postlapsarian landscape. The production

began without warning--the noise of an explosion, incredibly loud,

while the lights were still on. A woman with tattered clothing

and small, inadequate, wings walked to edge of the stage and screamed.

It didn't sound like a stage scream. She repeated the scream.

The sound design through many parts was painfully loud. I can't

remember the last time a piece of theater hit me with visceral

fear: probably an elementary school trip to Madison "Scare" Garden.

Many of the other workshop participants concurred, and one added,

"I felt like I was present at something, that I wasn't actually

allowed to see."

The production was divided up into episodes,

and the woman returned several times, always screaming. There

were two other homo sacre figures: a dancer pacing on

all fours, and a naked, embryonic man. These individuals were

juxtaposed with rigid monk-like dancers who would always appear

as a ceremonially choreographed group. In contrast to the homo

sacre figures, Tame Iti appeared twice as a figure of strength.

He was incredibly commanding, with tribal tattoos across his chest

and face.

When we fellows discussed this production

as a group, the purple dramaturg began a well-rehearsed complaint:

"This was nothing more than cold, calculated, producer's theater,

designed to turn a profit on the international festival circuit

with some indigenous references and the freak show appeal of a

guy with a tattooed face." A set designer asked the dramaturg

to tell us more about the company and how he knew that it had

been solely designed for the international market. He hesitated,

"well, no, I don't really know anything about the company. But

it's just so obvious."

***

After finishing my undergraduate degree

in New York, I ran off to Berlin to join the theater. I got a

nose ring, took up smoking, and adopted a cat, whom I named after

a Wagner heroine. I was an expatriate, see. Hemingway would have

had something to say about me:

You've lost touch with the soil. You

get precious. Fake European standards have ruined you. You drink

yourself to death. You become obsessed by sex. You spend all

your time talking, not working. You are an expatriate, see.

You hang around cafés.

So perhaps it is partly out of personal

nostalgia that I found the high point of the Edinburgh International

Festival to be Elevator Repair Service's The Sun Also Rises

(The Select). Short of arguing that Paris in the 1920s was

a colony of ex-pat Americans, or that Elevator Repair Service

comes from the former colony of New Amsterdam, it's hard to see

how The Sun Also Rises fit the theme of colonialism.

But it did resonate with my experience of "oceans apart," and

the production was so rich in imagination and humor that for once

I was glad the festival directors didn't take their theme more

seriously.

The

Sun Also Rises is Elevator Repair Service's third production

based on American literature of the 1920s. It is not so much a

dramatization of the novela as a staging of it. Mike Iveson plays

Jake Barnes, the narrator of Hemingway's novel. He begins the

play with a long expository passage taken verbatim from chapter

one. Throughout the staging, director John Collins plays with

Barnes' simultaneous roles of narrator and character. At one point,

Barnes shouts, "Why did you do that?!" then immediately drops

his voice: "… I started to say but held back."

The

Sun Also Rises is Elevator Repair Service's third production

based on American literature of the 1920s. It is not so much a

dramatization of the novela as a staging of it. Mike Iveson plays

Jake Barnes, the narrator of Hemingway's novel. He begins the

play with a long expository passage taken verbatim from chapter

one. Throughout the staging, director John Collins plays with

Barnes' simultaneous roles of narrator and character. At one point,

Barnes shouts, "Why did you do that?!" then immediately drops

his voice: "… I started to say but held back."

Elevator Repair Service has a remarkable

ability to introduce slapstick elements that become funnier through

repetition. While the set appeared to be a realistic French brasserie,

the bar top was actually a sound board on which actors controlled

the production's sound design (a running joke of sound effects

that don't completely correlate to staged action). The furniture

of the brasserie was used to enact every episode of the novel;

the tables became trout in one scene, bulls in another.

About two-thirds of the other fellows

left the theater at this show's intermission. When we discussed

the production the following day, I was the only native English

speaker in the room. Of the handful of Germans with varying levels

of English proficiency who condemned the play, not one was willing

to admit that his or her feelings might have something to do with

an inability to understand the nuances of the language. They agreed

that there was simply too much text, rather than that there was

too much text for them to understand. On the one hand, this easy

dismissal of "too much text" speaks to the expectations we have

developed on both sides of the Atlantic that close adherence to

a text is a sign of conservatism and lack of imagination. On the

other hand, this also says a certain amount about general German

condescension vis-à-vis American theater. Among many of the other

fellows, Germany was the only possible reference point for innovative

theater. One German director (who had just finished assisting

Hans Neuenfels in his lab rat production of Lohengrin

in Bayreuth) suggested that Elevator Repair Service was trying

to emulate German Regietheater, but doing it badly. Another

director proclaimed that she wasn't surprised at the play's mediocrity

because "I was in New York twice and I can tell you there is nothing

happening in theater there. I mean, seriously, 0.0 theater." Another

chimed in: "I went there once too, and she's right--there's really

nothing!"

Flying westward that evening, I was relieved

to be returning to my little island without theater. If there

was anything that spending ten long weekends with a roving group

of German critics was good for, it was psychological repatriation.