Unfinished Stories

Charles L. Mee, Jr.

in conversation with Caridad

Svich

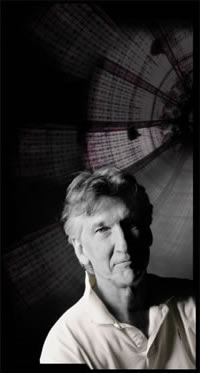

Dramatist and historian Charles L.

Mee, Jr.'s plays include The Murder of the Investigation

in El Salvador, bobrauschenbergamerica, Big Love, The Berlin Circle,

Wintertime, and the text for Vienna: Lusthaus. His

work has been produced by theaters across the U.S. and abroad,

including New York Theatre Workshop, Actors Theatre of Louisville,

Steppenwolf Theatre, BAM, and McCarter Theatre. He has engaged

in successful, significant collaborations with the directors Anne

Bogart (and SITI Company), Tina Landau, Ivo Van Hove, and the

choreographer-director Martha Clarke. This interview was conducted

online December 2003-January 2004, as Snow in June, Mee's

collaboration with director Shen Zi-Yeng and composer Paul Dresher,

was running at American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

At this time, Mee had begun work on a Joseph Cornell project with

the SITI company, to be directed by Anne Bogart, which will premiere

in the 2005 theatre season.

CS: So, let's start with what is indeed familiar territory, but

nevertheless consistently engaging and vital to address: you re-use

forms and stories, you re-make them for the contemporary world.

When is the familiar familiar in a sad boring way and when is

the familiar familiar in an ancient blood-curdling way?

CM: I take stories the way Aeschylus and

Sophocles and Euripides and Shakespeare did. None of them ever

wrote an original play, and, since they are among the greatest

playwrights who have ever lived, I thought it would be worthwhile

thinking of trying to do what they did. So I appropriate stories

(half the time, anyway; the other half I make up). And then to

the appropriated stories I add appropriated texts from other sources,

so that I make a collage of the materials of the world that we

have received, and also of the world we are in the process of

making at the moment: this seems to me what people do in their

daily lives. I think a story is still vital if it is still being

made. If something is taken as finished, then it is dead; if something

is taken as unfinished, then it is vital. This is how we make

our lives, and, since we only get one life on earth, this seems

urgent, the most urgent and important thing we do.

CS: It's true that Shakespeare, Euripides,

and Sophocles didn't write original plays. They appropriated sources

and fashioned them anew. I think there has been, however, a premium

placed on "originality" as a concept in modern theater, and it

has dis-allowed to a great extent the free-wheeling ability Shakespeare

and Euripides (and even Brecht) had with re-shaping stories, re-imagining

them, and re-claiming them for their time. It is as if a value

judgment is placed on contemporary dramatists if they write "original"

work versus "source-driven" work, i.e. that if it is "original"

it is somehow worthier. I think such a value judgment reflects

a misunderstanding of the artistic process because, in the end,

aren't we all re-making stories whether they be from our own lives,

our friends' lives, our lovers' lives, or lives told in fiction

and history? Moreover, what do you think the (and I think it is)

particularly U.S. preoccupation with "originality" in the arts

comes from?

CM: I really don't know where the preoccupation

comes from. Maybe it's a byproduct of Renaissance individualism.

The current obsession, though, comes from the copyright law. I'm

sure you know there was no such thing as copyright in the time

of the Greeks and Shakespeare. In Western Europe, I think, the

Pope eventually became weary of having to support so many clamoring

artists and so began to issue Papal bulls giving chosen writers

the right to copy their works, or to have them copied. In this

way, the Pope distributed the cost of patronage (and democratized

it). And that model has grown, obviously, as a way for artists

to support themselves. It puts a premium on a certain kind of

originality. It seems to me, though, as corporations have taken

an increasing interest in owning copyrights and using intellectual

property as a basis for corporate valuations, the original intent

of copyright law to support artists and nurture the arts and sciences

has become skewed. It seems to me, in fact, that the law stifles

development of art and science. To the extent that America has

developed capitalism more energetically than many other countries,

it may be that this preoccupation is a little stronger in America

than elsewhere.

CS: Are you aware that you have influenced

a generation of playwrights who are now more likely to try adaptations?

Is there something about our cultural moment that begs for adaptations

of the big stories? And do you define a "big" story?

CM: I'm very aware of being influenced

by others all the time--but not aware that I influence anyone

else. And--this is a small point--I don't call what I do adaptations.

Any more than I would call a play by Aeschylus or Shakespeare

an adaptation. We are all engaged in the process of reconsidering

and recreating the things that have been given to us by our lives

and histories, and then seeing what can be made of that. Nothing

comes ex nihilo. There are stories that playwrights have worked

over for a couple thousand years, and so I guess that some of

those stories have something extremely compelling about them--and

I go to them to see what that might be, to see if they are still

compelling, and, if they are, what about them is still alive and

compelling, what they have to say about what human beings are,

and what human beings might become.

CS: Your latest cycle of plays was about

love . . . are you done with love for the moment? Or is there

more theatrical love to be had?

CM: At the moment, I'm on to other things.

I've done a lot of "political" plays in the past, and have a couple

more of those that I've been meaning to get back to. So I won't

do any love plays for a while, probably. But I do think it is

an inexhaustible subject, so I'm sure I'll return to it. In one

of my plays, Fetes de la Nuit, a character is asked why

he talks always about love, and he says (inspired by the table

of contents of a book by Foucault):

Because

love

love begins a discourse

with anxiety

remorse

longing

connivance

dependency

embarrassment

drama

brutality

identification

unknowability

jealousy

languor

vengefulness

monstrousness

cruelty

insomnia

crying

gossip

loneliness

tenderness

isolation

truth

the will to possess

lying

remembrance

suicide

ravishment

because

in love

we come to know what it is to be a human being

what it is to be human today

because

if we humans see who we are in our relationships with others--in

all our relationships--erotic, poetic, political, economic, still

the way we know one another most intimately and deeply

how we are when we are free

and how we are unable to be free

it is in our love for one another.

And so, if we are to know what it is to be human

we know that best when know how we are in love

what sort of species we have become in our time

by what sort of love we've become capable of.

CS: Wintertime, for instance,

could be described as a colleague has said to me, as a "platonic

farce." It has a specific level of philosophical and theatrical

grace. Do you love philosophical dialogues? Can theater be a place

for philosophical dialogues? How and how not?

CM: I got polio when I was fifteen years

old. Until that time, I'd never read a book, only comic books.

And then, when I was in the hospital, an English teacher of mine

brought me a copy of Plato's Symposium. And I read it

and asked for another Plato, and then another and another, so

that, before I could again hold a book with more than three fingers

of one hand, I had read all of Plato. I was drawn to those dialogues--full

of conflicting ideas, passions, of the sort I was feeling, flat

on my back, at the time. And then I started in on Aristotle. And

I think all the time these days that Aristotle was right, that

human beings are social animals, that we are the creatures not

just of psychology, but also of history--of culture and politics

and economics--and so I've always tried to write plays that go

beyond psychology and embrace a larger understanding of what makes

humans human, and what makes our world as it is. So, yes, Plato's

warring passions, Aristotle's expansive understanding of the human

creature: these have been my dramaturgs.

CS: How do you use burlesque or vaudeville...musical

numbers in the middle of text, glorious butt-dances in the middle

of text? And why? There is such an open-ness to theatrical joy

in your work. Where does it come from? How would you characterize

it?

CM: I've come to believe--with Shakespeare,

and with the postmoderns--that art is most pleasurable not when

it closes us down, narrows our perceptions and sympathies, draws

boundaries of appropriateness or goodness, but when it opens us

up. And I could add lots of justifications for the way I juxtapose

high and low, tragic and farcical, intellectual and physical,

how they pop against one another, how they make one another more

vivid when seen in such surprising contrast--but, the truth is,

I just love a wonderful time in the theater, and, for me, a wonderful

time includes something challenging to think about, something

to feel deeply and sometimes shatteringly, and some plain hilarity

and joy and stupidity and release.

CS: You are working on a piece about Joseph

Cornell. His memory-boxes in particular are so rich and detailed,

and highly idiosyncratic. Unlike say, Bob Rauschenberg's work,

which inspired your collaboration with the SITI Company, Cornell's

work has often been described by critics as hermetic, and mysterious,

and outside the Pop world. What are your thoughts on Cornell and

how his work can teach us today about investigating the world,

self and memory?

CM: Rauschenberg was a wonderful figure

to start with: his energy is so positive, happy, colloquial, and

inclusive before anyone knew there was such a word. It's so connected

to daily life, so inspiring in its democratic sympathies, it was

easy to hear it start talking and living on stage. Scenes made

themselves. Cornell, by contrast, I find sad and strange, weird,

kinky, a little off-putting. But there is something about him--drawn

down deeply inside himself, following some set of impulses so

distant and peculiar--that he seems like the very soul of the

artist--and, indeed, the very soul of any human who feels herself

to be on a journey in life that is essentially internal, that

only after a long while rises to the surface and seems to resonate

with others. This will be hard to put on stage. But one thing

I love about beginning with the life of an artist--and not trying

to do a bio-pic, but trying to do a piece "inspired by" a way

of seeing the world-is that it leads to discovering very different

theatrical forms. I think about Euripides and Shakespeare and

Brecht all the time, but I've also learned a lot about how to

make theater from Max Ernst and Rauschenberg, and now, I hope,

Cornell.

CS: When you are working on a piece, when

and how do you decide which container, which form, is best suited

to encasing the material you have written and/or assembled?

CM: Often I just steal a story--from Euripides,

say. And then I smash his play to bits and write a new play that

lies, as it were, in the bed of ruins of Euripides. So Euripides

supplies the form. I've done the same with Shakespeare and Brecht--and

Rauschenberg and Cornell. But, if I just start out with some other

impulse or hunch and write a play that is not derived from any

other source, then I just throw stuff out and trust Rauschenberg's

example. Rauschenberg made paintings and assemblages based, he

thought, on chance. But, of course, what he discovered was that

he couldn't "do" chance. His psyche determined his choices at

every turn. And so, instead, he learned to trust his own psyche--to

trust that whatever he did, it would--it couldn't be any other

way--be shaped by who he was, by what he loved, what felt good

to him. And, if he trusted that somehow, somewhere--because he

wasn't from Mars--his psyche was humanly coherent, the finished

work would be coherent, too. And that's what I have to trust when

I do something that doesn't start from a previously made form.

CS: Would you elaborate on how the Rauschenberg

piece came to be, and what the process of working with Anne and

SITI was like for you? How did the text take shape? How was the

experience either a new way of working or similar to ways you

have worked before with other collaborators?

CM: I've loved Rauschenberg, and been inspired

by his collagist way of making work, since the nineteen sixties.

He has always seemed to me to be terrifically open, small "d"

democratic, optimistic, vigorous, unafraid, free, egalitarian,

again, inclusive before the word was in the common vocabulary.

He makes art by picking junk up off the street--not merely ignored

stuff, but absolutely rejected stuff--bringing it back inside

his studio, putting it together and saying, "This, too, is beautiful."

So I started by looking at his work, picking some of my favorite

images and themes--a stuffed chicken, Martin Luther King, an astronaut--and

making a list of the things that recur in Rauschenberg's work.

And then I made a list of texts that made me think of: chicken

farmers talking about starting a chicken business, astronauts

talking to Houston, an astronomer talking about the stars. And

then a list of possible events inspired by those images and texts.

Actions. Songs. And I took those into a workshop with eight or

ten people the SITI Company had brought together--not writers

alone but also actors, a choreographer, a sound designer, an administrative

person from the SITI office, a couple of students. And they did

what I did--made lists of things they saw in Rauschenberg, what

it made them think of, texts they heard or remembered or thought

to compose. The rule of the workshop was: don't bring in anything

you don't want to have stolen. Anyone can steal anything I brought

in to make whatever piece they might want to make, and I could

steal whatever they brought in.

So I emerged from the workshop with lots

of ideas, and some wonderful pieces of text. One of the participants

had a friend who was a truck driver, who had written her about

starting out at five o' clock in the morning on his cross-country

route--and then went directly into the piece. So I put all this

stuff into some pages and took that to Skidmore College where

the SITI company teaches a group of anywhere from 50 to 100 students--most

in their twenties, some older--every June for four weeks. And

they all improvised "compositions"--little scenes bringing together

chunks of text, songs, dances, movements, physical activities.

I took all this stuff home, and I thought:

now this is a mess. This is not a theater piece, it is just a

bunch of random associations by a disparate group of people responding

to the work of Rauschenberg. I thought: what would Rauschenberg

do? I thought: he would just choose his favorite stuff out of

it all and call that a piece. So that's what I did. About half

of it is stuff I wrote or thought of, and half is stolen. That

was a "finished" script. And then the SITI company took the script

and made compositions of my compositions, and put other actions

with my texts, and made up dances--and that was the finished finished

piece.

CS: You majored in history and literature

at Harvard, and you worked as a historian for a long time before

resuming your interest and life in the theater. What drew you

back to playwriting, and why? Do you ever think of your theater

writing as an extension of sorts of your work as a historian in

some way, in the telling of national and international stories?

CM: History, as a discipline, claims that

it is possible to frame rational sentences and paragraphs that

will contain the reality of the world. And yet it seems to me

that the reality of the world so often makes me want to yell and

shriek and cry out and tear my hair--that it engages my heart

as well as my head, whether I want it to or not. And so, in time,

the writing of history just wore me out. I still read history

a lot, and admire wonderful writers of history. But to me the

form itself seemed too narrow and constraining to contain the

world as I saw and felt it. On the other hand, the theater wants

us to use both our heads and our hearts, and so that feels good

to me, it feels like the world, and that's where I feel most like

myself. Inevitably, having spent twenty years writing about politics

and history, I take that with me as I write plays. I think of

the characters I write as living in this larger world I've written

about, and living in a particular epoch, and occupying some place

in the world as it is becoming.

CS: You have collaborated with leading

stage directors Anne Bogart, Tina Landau, Robert Woodruff, Ivo

van Hove, Martha Clarke, and Les Waters. Would you speak a bit

about what you have learned from working with these directors,

and how the specific collaborations have informed your writing?

CM: I love theater that is made of music

and movement and text. It seems to me that this is what most theatre

has always been made of--and, in most of the world, still is.

But the theater of western Europe since Ibsen--maybe beginning

a little earlier--has been a theater of staged literary texts.

And so most directors have become masters of staging texts. The

directors I love are the directors who imagine that their job

is, rather, to create a three-dimensional event in time--in which

text finds a place along with these other theatrical elements.

So these directors mobilize an event filled with music and movement

and text. And from them--and from the work of Chen Shi-Zheng and

Robert Lepage and Pina Bausch and Sasha Waltz and Alain Platel

and some others in Europe--I learn how to write for this sort

of theatrical event. When I write, the text never comes first.

First I see an event on stage, and, when I've begun to see it

very clearly and in detail, then it just starts speaking.

CS:

Snow in June premiered at ART recently. It is a unique

project. Would you expand on the making of this piece, and how

it came together? What questions came up during the process of

this cross-cultural artistic exchange (in terms of direction,

text and music), and in what way did the questions lead to creative

answers for director Chen Shi-Zheng, composer Paul Dresher, and

yourself?

CS:

Snow in June premiered at ART recently. It is a unique

project. Would you expand on the making of this piece, and how

it came together? What questions came up during the process of

this cross-cultural artistic exchange (in terms of direction,

text and music), and in what way did the questions lead to creative

answers for director Chen Shi-Zheng, composer Paul Dresher, and

yourself?

CM: With Snow in June, Shi-Zheng

came to me with a 13th-century Chinese play and asked if I would

do a version of it. I thought the original play was magnificent,

and told Shi-Zheng I thought he should just do that, but he wanted

something new. The original is about a young Chinese woman who

is badly treated in a dozen ways, is brought to trial for a murder

she didn't commit and unjustly executed, and she rises from the

dead to find her father, who is by now an official in the central

government in Beijing. He hears her story and goes out to the

provinces to set everything to rights. In short, the moral of

the story is, if only the central government knew, everything

would be okay.

So I took it and set it in Queens, New

York, today. I threw away the ending and had the girl rise from

the dead and murder everyone in revenge, so that, I guess, the

moral became: you can take the nicest, sweetest, best human being

and, if you treat her badly enough, turn her into a homicidal

maniac. All the characters and language and events are from New

York today, though the core characters and the essential plot-line

remain the same. Paul Dresher asked me to write some songs, and

I said I had never done that, but he said, that's okay, just write

whatever and I'll set it to music. So whatever is just what I

wrote, and lots of songs came out.

When Shi-Zheng took it into rehearsal,

he felt it was too linear and narrative, so he sort of threw it

up in the air and scrambled the scenes randomly and worked on

them a while that way. But then, a couple weeks into rehearsal,

he decided he wanted to return to my chronological order, which

he did, but leaving out a lot of the narrative chunks and stitchings

so that it remained surreal, expressionistic, of another world

altogether--somewhere between my original linear treatment and

his dreamlike world.

As you can guess from this, I am a guy

who usually leaves directors completely alone. I never go to rehearsal,

unless specifically asked by the director to come in for a day

or two. So the director and the actors are as free to do their

thing as I was to do mine, and in this way lots of different sorts

of productions of my plays are done. There is no such thing as

a definitive production. I do it, I think, because some years

ago it struck me that I thought the playwrights who got the best

productions were the dead playwrights--and maybe that's because

they didn't go to rehearsal. So, ever since, I've tried to behave

like a dead playwright.

CS: Many of my U.S. contemporaries in dramatic

writing have expressed their desire to live in a culture where

the playwright's voice is part of the public discourse. There

is a general feeling among us that the dramatic form, that theater

in this country, is considered an elitist, rarefied art, disconnected

from the world -- from social, political and human concerns --

and therefore irrelevant. What are your thoughts about the playwright's

position in society?

CM: I don't think about the playwright's

position in society. I do think that if a person wants to stop

war or change economic relationships, he or she should get into

politics--and do it right away. Or, less directly, write polemics.

Or maybe even journalism. Or, if popular propaganda is wanted,

then the only medium worth writing for is television, maybe movies.

To paint paintings, compose music, write novels, write plays:

these have nothing to do with changing the course of the world

in the near future. Maybe they have something to do with contributing

to the nature of the culture over the long haul--in the way that,

say, philosophy or plumbing might, even though they have little

to do with the immediate public discourse.

But art is not a subset of politics or

ethics. It is not justified by an appeal to some other purpose.

It is its own calling, with its own agenda or agendas, subject

to no other. I'm really not a person who makes characters in my

plays mouthpieces for my own thoughts, but it just happens that

a character in bobrauschenbergamerica said something

I agree with:

art is made in the freedom of the imagination

with no rules

it's the only human activity like that

where it can do no one any harm

so it is possible to be completely free

and see what it may be that people think and feel

when they are completely free

in a way, what it is to be human when a human being is free

and so art lets us practice freedom

and helps us know what it is to be free

and so what it is to be human.

Still, if you believe that human character

is formed not just by psychology but also by history and culture,

as I do, then you are destined to write "political" plays in some

sense--not plays addressed to an issue of the moment necessarily,

but political in the broadest sense. Whether those plays then,

in turn, affect the culture is up to the culture.