Tribunals at the Tricycle

Nicolas Kent in conversation with Terry Stoller

Led by artistic director Nicolas Kent,

the Tricycle Theatre, in Kilburn, north London, has been at the

forefront of documentary theatre, examining subjects from war

crimes and human-rights violations to institutional racism. Since

1994, Kent has broadened the Tricycle's rich repertoire of socially

conscious plays to include stagings of edited government inquiries,

which are generally not televised in England. The tribunal plays

have established the Tricycle as an important outpost of political

theatre in Britain.

The Colour of Justice

(1999), which Kent considers his most successful venture,

is taken from an inquiry into police mishandling of an investigation

of the murder of a young black Londoner, Stephen Lawrence. The

Scott Inquiry into arms for Iraq was the focus of Half

the Picture (1994), and war-crimes trials were under

examination in Nuremberg (1996) and

Srebrenica (1996). The Hutton Inquiry--launched

after the suicide of Dr. David Kelly, a source for the BBC's report

that the government had "sexed up" its reasons for going to war

in Iraq--became Justifying War, the

Tricycle's fall 2003 production. And in spring 2004, the Tricycle

launched its own investigation to produce a verbatim play on the

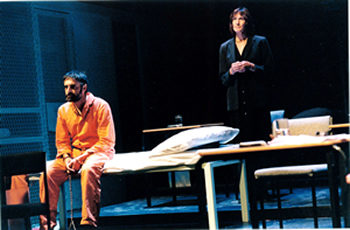

plight of the British detainees at Guantánamo Bay. That play,

Guantánamo: 'Honor Bound to Defend Freedom,'

transferred to the West End after a run at the Tricycle, was

remounted in New York City and is scheduled for productions in

California, Italy, New Zealand, and Sweden. In April 2005, the

Tricycle will premiere Bloody Sunday: Scenes from

the Saville Inquiry, taken from the investigation

into the 1972 shooting of civil-rights marchers by British soldiers

in Ireland.

I spoke with Nicolas Kent in January

2005 in London. Interestingly, that was the week the British government

announced the release of four British citizens who had been held

for some three years at Guantánamo Bay. One of these citizens

is a central character in Guantánamo.

Terry Stoller: In articles

about the Tricycle Theatre and the tribunal plays, it's been implied

that this theatrical form is more relevant than journalism. Do

you think that's true?

Nicolas Kent: I don't

know if it's necessarily more relevant. I think what it does is

it gets a different perspective. The problem with journalism is,

because of the television age we're in and even newspapers, we're

getting sound bites. We get very short coverage of stories. You

read an article in a newspaper, and it lasts two to three minutes,

four minutes to read it. On television you see it in one minute,

and people don't grapple with issues. They don't get to the bottom

of issues. In the theatre you've got a captive audience. The house

lights go down. The doors are closed, and people stay in there

and they wrestle with something for an hour and a half. I think

also the group reaction to things is very important. Your anger

or your cynicism or your praise or admiration for something is

confirmed by the other members of the audience, whereas if you

read something alone in a room, that isn't quite so. It can deal

with [an issue] in much more depth too. If you're taking a public

inquiry, which is what we mainly do, [it lasts] maybe one month,

maybe six months, maybe nine months, or in the case of Bloody

Sunday, four years, and you can't get an overview of it.

You read little bits in the newspaper and then you get bored and

you come back to it and you revisit it. So to get an overview

of an issue, I think the theatre can be incredibly useful.

TS: This question doesn't

have as much to do with the tribunal plays, as with Guantánamo

['Honor Bound to Defend Freedom']. When you take on the role

of a theatre journalist, do you think you can be held to the same

standards we assume that other journalists adhere to?

NK: I think it's vital.

TS: How do you do that

with people who perhaps are not trained in journalism?

NK: I think you only do

it within certain rules, which are your own morality really. You

don't distort anything anyone's told you. You're very careful

about upholding the truth of what they've said. And if you're

given a source, you don't betray the source. If someone says I

don't want you to broadcast this or I don't want you to say this,

you certainly don't say it. So I think the ethics are exactly

the same. Journalistic ethics are common sense.

TS: Beyond the ethics,

what about needing two or three sources in order to say, "This

is fact." How do you think that might work in the theatre?

NK: I've never done plays

that do that because I'm always using what people have said. So

the source is them. I've never yet done a play where I've made

an allegation and it's me making the allegation. It's always other

people making the allegation, whom I report accurately, who don't

remain anonymous. So in Guantánamo, the fact Jamal al-Harith

says, "We were tortured," I don't have to question that. He said

that. So you can take it and believe it or disbelieve it. It's

up to you as an audience to do that.

TS: Let's say you represent

a person, and you know certain things about that person, and you

suppress that information to make a dramatic point.

NK:

Ah, yes. I suppose to some degree you might do that. If you'd

played the words like [one person represented in Guantánamo]

did to us, then he might come across as a less persuasive person.

So I suppose to some extent--in order to allow the words to speak

for themselves rather than the way he's put over them--we've stripped

him back a bit. But I don't see that as a distortion. I suppose

it's a distortion if he were on trial because the jury would be

looking at his body language as well as what he says. And so we've

changed the body language very slightly. But we've not changed

what he said. You know, some people can be very innocent in something

and give the impression of being guilty because they're foreign

to us. If he were an English person and he'd said these things

in the same way, then I might have been a little more careful

in trying to portray [him].

NK:

Ah, yes. I suppose to some degree you might do that. If you'd

played the words like [one person represented in Guantánamo]

did to us, then he might come across as a less persuasive person.

So I suppose to some extent--in order to allow the words to speak

for themselves rather than the way he's put over them--we've stripped

him back a bit. But I don't see that as a distortion. I suppose

it's a distortion if he were on trial because the jury would be

looking at his body language as well as what he says. And so we've

changed the body language very slightly. But we've not changed

what he said. You know, some people can be very innocent in something

and give the impression of being guilty because they're foreign

to us. If he were an English person and he'd said these things

in the same way, then I might have been a little more careful

in trying to portray [him].

TS: Richard Norton-Taylor

[Kent's collaborator on most of the tribunal plays] has quoted

David Hare as saying, I work like an artist, not a journalist.

I'm wondering what you think about that because you're making

art out of journalism.

NK: David works differently.

Did you see Stuff Happens?

TS: I didn't. I did see

The Permanent Way.

NK: Let's take The

Permanent Way. The Permanent Way was not verbatim

theatre in that David made twenty-five percent of that up, and

I think it was very difficult to distinguish what were David's

words and what were the actual words spoken. I had some difficulty

with that play for that reason. And I don't know if I really respect

what he's saying there. Obviously he's bringing a theatrical consciousness,

and you can say that's artistry to some degree. It's artistry,

yes. But on the whole, either you're doing journalism in the theatre

or you're doing make-believe in the theatre. And I think it's

a rather uncomfortable straddling of the two. I don't want to

go to a play and not be certain if it's true, exact words. We

made one line up in the whole of Guantánamo, which was

really just to introduce the character. When the Foreign Secretary

came on, we said the Foreign Secretary will not be taking questions

after this statement. Well, the Foreign Secretary didn't take

questions after the statement, and it's not unreasonable to suppose

an official might have said that. I don't know whether an official

did say that. But it was the only line made up in the entire play.

And it was done for a reason, and when we print the plays, I don't

know if that one was, but all the other plays we printed, if we

made up anything, we've always put in square brackets. And we've

only made things up for clarity.

TS: Your theatre has

been called the most valuable home of political theatre. Do you

think there's something unique about the theatre, where it is,

who goes there, that makes it a place to do political work?

NK: It seems extraordinary

that we are called the most important theatre in Britain, political

theatre. Everyone keeps repeating it. I think it just shows the

paucity of political theatre in Britain. I find it a bit of an

overbearing title, to be absolutely honest. What happened is that

I had a predecessor who first set up the theatre, and he had four

planks of policy, which was to do new work, work that reflected

the ethnic minorities in the area, work for, by and with women,

and work for and with children.

TS: You still have that

listed on your website.

NK: And those are still

the mission statement effectively. And what happened is that I

suppose inevitably our two biggest communities are the Irish community

and the black community--also to some degree the Asian. When I

took over, those two communities were at war. And we had a cold

war going on, but we also had a hot war going on in South Africa

and in Northern Ireland. And that affected very much the communities

in Kilburn. [The black community] was affected by the racism of

the British government. Margaret Thatcher didn't come out anywhere

near strongly enough against apartheid. It was a major issue in

this country, because it was an ex-colony of ours and we were

responsible. So we had a very strong relationship with the Market

Theatre in Johannesburg, and we took in lots of South African

work. Equally if you were Irish, you had the situation that bombs

were going off all over London in regular intervals. You could

hardly take a tube journey anywhere and know that you'd ever get

to your destination without being stopped or disrupted because

of a bomb threat.

TS: What year was this?

NK: This was in the '80s.

The terrorism thing was going on, so inevitably we were doing

plays about Ireland too. So when both situations almost at the

same time got solved and the Berlin Wall came down--so the polemics

between communism and capitalism disappeared, and it all became

about how you managed an economy and not the political ideology

of all that--we sort of lost a role. Ironically we were very political

in those days, but we weren't considered to be political because

we were just doing theatre. I was looking for something to do,

really, just to make it more interesting to direct plays. I didn't

want to just do one classic and one new play, and out of that

came the Scott Inquiry and that started a tradition of verbatim

theatre which had actually been done in the '60s and '70s by John

McGrath, the 7:84 theatre company, and even by David Hare with

Fanshen. So I wasn't doing anything spectacularly new,

but it seems like I reinvented the wheel, and I think I've got

absolutely false credit for it. I'm not totally displeased everyone

thinks it's so wonderful, but it is a bit extraordinary in a way

because I don't think we've done anything totally different. Perhaps

the one thing we have done is we've been not polemical. What we're

doing is saying, "Here are the facts as we see them. You make

up your mind." But by the mere fact we've chosen the issue we've

chosen, we've actually made up our mind. You know, I wouldn't

have done the Scott Inquiry if I didn't believe the British government

was exporting arms to Iraq and shouldn't have been doing so. I

wouldn't have done the Hutton Inquiry if I didn't believe the

dossier for going to war in Iraq had been made up.

TS: Is the Kilburn community

interested in the documentary work? I know you get a lot of people

from the greater London area when you do those plays.

NK: I think so. I think

the community are very interested. It's very difficult to know.

We have a lot of the journalistic intelligentsia who come and

see the stuff, who are local to us, but we also have a lot of

very poor people. And when we do the Bloody Sunday inquiry, which

I'm working on at the moment, there will be a lot of working-class

Irish people coming to see that.

TS: Is that why you're

doing that piece, because of the Irish community?

NK: Well, I suppose that's

a little bit of the thinking. What happened was after the success

of the Stephen Lawrence [Colour of Justice], it seemed

quite natural and there was this appetite. Bloody Sunday does

figure quite large in the British psyche. It's a major, major

thing--troops opened up fire, killed 13 people. That's a lot of

people to kill. So we decided to do it. It was quite obvious we

were accredited, and quite a few people were interested in us

doing it. That was six years ago, and we didn't expect Hutton

to happen and we didn't expect Guantánamo to happen. And those

things have supplanted it. So I've been working on it for six

years.

TS: When was the inquiry?

NK: The inquiry finished

on November 22, [2004]. And it hasn't reported. We always do this

before the report. It will report probably in June, July, August

of this year [2005].

TS: You often have post-show

discussions. Do you think that this is an intrinsic part of this

type of theatre? And what do you think happens when there isn't

one?

NK: It's quite interesting,

that question, because I'm wrestling with it at the moment, because

Bloody Sunday is likely to be very long. It's likely

to be about three hours with interval, so it doesn't give us a

room for post-show discussion. And I was thinking, What are we

going to talk about with Bloody Sunday? There aren't

really any issues in Bloody Sunday. It spills over into

the Iraq War in a strange way about how an army of occupation

works. But there are not that many issues. With Nuremberg,

I think we hardly had any post-show discussions. It just didn't

seem necessary. But then when we did Srebrenica, we had

endless post-show discussions because it was about where we moved

on in ex-Yugoslavia. So I think it's whether the issue is a live

issue and can be altered by people's behavior. And with the Lawrence,

it certainly could be altered, and so the discussions were invaluable.

You know the Evening Standard? Well, one of the post-show

discussions made the main headline on the front page of the Evening

Standard, because there was a bit of a row at it. Someone

had attacked the Lawrence family. It was: "Lawrence family in

onstage dispute," huge banner headline which was selling the newspaper.

TS:

Some critics complain about the bias in documentary works. Do

you have a problem with a documentary piece taking a point of

view?

TS:

Some critics complain about the bias in documentary works. Do

you have a problem with a documentary piece taking a point of

view?

NK: No, I don't. As long

as it honestly purveys its point of view. We don't have a point

of view, except as I said, by putting it on. Then people say you're

preaching to the converted or, as you say in the States, preaching

to the choir. I don't have a problem with preaching to the choir.

Max Stafford-Clark, who did Permanent Way, came to see

Guantánamo, and someone said it's all preaching to the

converted. And I overheard Max say, "Yeah, but I just love theatre

that preaches to the converted." Theatre that preaches to the

converted, or is accused of it, has, it seems to me, three major

defenses: one, it strengthens those who are converted into their

view to do something about the project; two, it quite often attracts

someone who is slightly wavering and doesn't quite know about

the problem but is vaguely interested in it in some way or other--it

strengthens their commitment to the project; and three, it quite

often gets someone in for completely spurious reasons, in that

they might have an aunt who has a second nephew who's in the show

or they might have thought Guantánamo was a wonderful

Cuban musical that they'd always wanted to see, and they've learnt

something. So in the end it doesn't matter very much whether it

preaches to the converted. What matters is whether it's full or

not full, whether people come.

TS: When I was reading

the English reviews for Guantánamo, I couldn't really

see in the critical response a rightist or a leftist point of

view.

NK: It's very interesting

because in the States we did get partisan reviews. There was no

question the New York Times was going to write us a good

review. I knew that before we ever started because we were a good

thing in their argument against the Bush regime, so we already

knew we were going to get half-a-page photo on the front cover.

The Wall Street Journal completely rubbished us. I mean

completely: It was polemical. It was left-wing bias. It wasn't

accurate. All those things. And you just thought, that's The Wall

Street Journal. There was an ax to grind there. So I was quite

interested that the reviewing was enormously political in the

States and [in England] it was completely objective, it seemed

to me.

TS: In terms of having

a real political effect, do you think the play Guantánamo,

for stirring up interest and getting more people passionate about

the issue, is connected with the releases from Guantánamo Bay

of the British detainees this week?

NK: It's a little bit--I

think the government [was] surprised at the tenacity of the British

public to plead for four Muslim "terrorists," in inverted commas,

or eight Muslim "terrorists" at the time, and they've been really

surprised by that. I think they got very surprised that the play

goes on in a little theatre in northwest London, which they don't

bother about but has then extraordinary reviews. And then suddenly

it's gone into the West End, and Tony Blair is asked and interviewed

if he's going to go and see it. How does a play go to West End?

It doesn't go to West End because no one wants to see it. So [the

government officials] put two and two together. And then the families

are slightly more robust. There's someone called Kathleen Mubanga,

who's Martin Mubanga's sister, who's been campaigning for Martin,

who didn't give a single press interview, wouldn't cooperate with

us on the play, came to see the play four times, found it intensely

moving, has been in touch a lot and suddenly started coming on

demonstrations and suddenly starting giving interviews to the

press. Well, all that helps. So, yeah, I think the whole issue

was on the tipping point, and the play may have been one hair

which just made the scales drop. I don't think it did much more

than that. With the Stephen Lawrence, the play had an absolutely

devastating and huge effect. It's still used to train police officers.

They use the videotape [of the play] as police training. And when

the play went out on television, it was viewed by twenty-three

percent of the national viewing audience on a Sunday night between

10 o'clock and 12 o'clock. That's a huge audience who stuck with

that play. It was quite a difficult play to digest.

TS: Some people talk about

documentary plays, oral-history plays, as being healing. Do you

see them that way?

NK: I think they're all

deeply healing. Healing in the sense of [Desmond] Tutu talking

about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa,

which said it was doing not a retributive justice but a restorative

justice. And I think that what public inquiries are there to do,

they're trying to look at what happened to a victim, be it David

Kelly or Stephen Lawrence or a businessman who was put out of

work because of the arms to Iraq scandal who later went to jail.

These are public inquiries to restore the British public's faith

in the law and the conduct of government. If you then take them

to a wider public, that really forces the healing process. [Guantánamo]

isn't a public inquiry, but it is a sort of inquiry. A lot of

Muslims came to see Guantánamo and the discussions we

did have. It's extraordinary. I've sat amongst a mainly non-Muslim

audience and I saw people care about Muslims. With [Colour

of Justice], there was a lot of expression of people who

suffered racial attack, physical attack. A lot of people started

talking about it and coming out of the woodwork.

TS: Do you think documentary

theatre is the right form for the contemporary world, because

of the way we live our lives now?

NK: I do think it is,

probably. Because what's happened now is politics have become

so complex and so difficult that the only way of dealing with

things is on single issues. People are very focused on single

issues, and the theatre can treat single issues, as can film,

very well and very effectively.