Tracking America

Heather Woodbury in Conversation with Caridad Svich

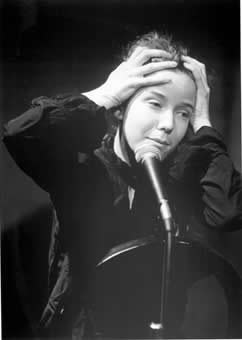

[Heather Woodbury's epic tales for

the stage take audiences deep into the unexamined crevices of

American life. In her solo-show "performance novel" What

Ever: An American Odyssey, Woodbury charts the stories of

more than a dozen characters that make up a cross-country, cross-generational

tapestry of outsider U.S. history. A raver from Oregon, a boho

octogenarian artist, and a street-wise, crack-addicted prostitute

are chief figures in What Ever's saga of displaced utopian

dreams. In her most recent multi-actor piece, Tale

of 2 Cities: An American Joyride on Multiple Tracks, fifty

years of Los Angeles and New York history collide in a live "mix"

spun by a young DJ. Spanning the years 1931-2001, the piece centers

on the razing of a Latino barrio to build Dodger Stadium and an

attack on an elderly Brooklyn woman at the Ebbets Field Housing

projects. The text samples news stories from the past and present,

creates an imagined audio grid of Los Angeles and New York, and

mixes these with extended narratives of the extraordinary ordinary

people who live in these cities. What distinguishes Woodbury's

work as a writer-performer is her ability to capture a wide variety

of linguistic idioms. High and low, uptown and downtown, country

and city sounds all mix effortlessly in her texts. Poised between

fiction and drama, her work refuses to enforce strict generic

boundaries on the linguistic and imagistic streams of thought

that enter consciousness. Elaborately woven and unruly, her plays

are documents of forgetting -- of neglected and disposable pockets

of a country tossed out onto the junkheap of history -- that are

recorded by Woodbury's exacting and compassionate sensibility.

I first met Woodbury in Atlanta, Georgia in 2005 where we were

both contributors to Dad's Garage Theater's Live and Uncensored

8 ½ X 11 Festival. Since then we have kept up with each other

as we have traveled disparate but simpatico artistic routes. This

interview was conducted via e-mail from September 2006 to January

2007 as Woodbury was writing, staging and performing Tale

of 2 Cities in Los Angeles at UCLA's Live Series and in New

York City at PS 122, where she is currently in an artistic residency.

]

Caridad Svich: Realism

is often a narrowly defined genre, especially in the American

theater. We are obsessed with realism and its supposed by-product

and chief value: authenticity. In the process, we often forget

that it is all, after all, artifice. How do you approach the realistic

conundrum?

Heather Woodbury: I like

to tell students, and other captives to my windy pronouncements,

that it's called realism and there's a reason for that. Naturalism

is just another form of artifice, as is everything that happens

on stage. There was this article that Margo Jefferson wrote some

years back about how artifice is what distinguishes theater, or

actually, what makes it necessary and unique. In film the artifice

is much more total and enveloping and therefore less underlined.

Theater, from the outset, is totally false. There's a bunch of

people in front of you in the same room pretending to be elsewhere.

So, it's truth, or authenticity, as you call it, that we're looking

for by practicing these antics on a stage, which sometimes mimic

believable behavior and sometimes not. When the whole project

is overtaken by the pretense of being "real," then, in effect

ALL you're doing is being artificial; you're hung up on a staging

gimmick, essentially, and missing the boat on revealing anything

new or moving or funny about being human.

Artifice needs to be boldly acknowledged.

As a solo performer I had a scene in my play What Ever

where the crack whore Bushie is beaten to death by yuppies near

the Hudson River. Now, how does a person act out beating themselves

to death? It's absurd. It's the height of it, the yuppies screech

off in their car, and our bloody anti-heroine crawls to a cement

overhang, watches the sunrise and dies. So, during this sequence,

I had a big bottle of ketchup which I'd squirt all over myself

after the yuppie characters "exited." What I found was that the

audience would laugh and then be more horrified. By making them

laugh, and using the fake ketchup blood, I was breaking through

the "reality" of my story enactment, acknowledging that I was

one person pretending. This dissipated the suspension of disbelief

and made us all in one reality, a collectively imagined one, in

which we knew that Bushie wasn't "real" but at the same time,

we knew she existed and was beaten and kicked and bloody and dying

as the sun rose over the Hudson. So it made it less realistic

and more true. Somehow or another.

CS: A false dichotomy

is often imposed on new theater writing: if you are to write a

serious, political play and talk about the world, then it must

be, well, SERIOUS and not engage simultaneously in the magical,

outrageous, or frivolous aspects of culture. I'm amazed by how

embedded this kind of thinking still is.

HW: Yes, and yet I've

often thought that if one were to airlift, say, one thousand clowns

into a war zone, hostilities would cease, through puzzlement alone.

Art is on a different wave-length, a different vibration. It is

social and political BECAUSE of that, not in spite of it. I really

get tired of this demand from the arts funding establishment (which

is probably a passing along of a demand made on them by their

benefactors) for art to be "more" than art. For it to be social

work. You know, outline precisely how you are going to educate

and facilitate under-served communities. I believe wholeheartedly

in connecting people, especially marginalized people, but I dislike

when art loses quality in the name of inclusion. A work of theater

can celebrate a community without didactically speaking for it.

Let people speak for themselves. A lot of socially earnest theater

is neither fish nor fowl. It's this muddy mash of intentions,

where real people's experiences get grafted onto some Greek myth

or another. I say, let the playwright be inspired by the social

foment, by working with people on their own individual expression

but let the playwright -- or director, actor, whatever -- be a

complete individual too.

This de-glamorization is very old school

communist, the "don't wear lipstick at the rally or you're not

a real radical" syndrome. Ironically, these faintly Soviet or

cultural-revolution-style theories, of art having to empirically

and materially -- rather than transcendentally and spiritually--

serve the masses, are filtered down to the institutional theater

world through funders who are generally corporate. I'm always

amused how this outdated communist idea that imagination must

be sacrificed to the "team" or collective is alive and well and

flourishing in global corporatism. Okay, I went off on a tangent

here. The point I'm trying to get at is that corporate funders

want non-profit theater to prove how they are serving the under-served,

addressing social ills, but it's superficial and a kind of bromide

at best because they strait-jacket vision and imagination. Non-profit

theaters have so many commercial pressures AND pressures to demonstrate

this "feel-good multi-cultural all one big diverse family" social

good that they don't often enough produce work that is alive (and

I'm not saying it isn't good, but) that is alive enough to be

transcendent, to galvanize people. Sometimes art seems more possible

in the commercial world, where there's only the ideology of the

sale to contend with, not that plus lip-service to, without the

true support for, socially conscious ideals.

CS: What's doubly unfortunate

is that in all of this social realism has been branded with the

stamp of dullness and earnestness. But if you look at the roots

of dramatic realism, at Ibsen's plays, for instance… it's hardly

so.

HW: I think this may have

to do with class. Ibsen wrote candidly about the bourgeoisie.

People are afraid to deal with class and ethnic particularities

in American theater. So, you get a lot of stuff about upper middle

class people that is quite accurate and well done, but doesn't

really SEE any other classes out there, that just assumes that

their middle class existence is the human condition, and then

you also get works rather overly respectful of the oppressed classes,

which is de-humanizing. So, yes, it does get dull and limited

and you can see why people might run screaming from it.

CS: Aren't we writers

responsible, though, for seeking out and crafting new languages

(emotional, pictorial, linguistic) for our stages that reflect

the world?

HW: This is the question,

really, if theater -- maybe live performance of ANY kind -- is

to continue to offer something which can't be gotten elsewhere.

Theater is the original interactive site, virtual reality, conjuring

place. It, etymologically, is a "place" for looking at something.

So, it is an atmosphere. It surrounds us in the texture of our

contemporary reality. An example I use in music is that folk music,

almost universally, incorporates nature sounds: flutes imitate

birds; drums: water and thunder -- these aural signs composed

the contemporary life texture of tribal and peasant people of

the past. Now industrial rock music is the sound of the age of

industry -- of the machine, of thrashing, grinding, screeching,

pounding. So, those are scavenged from contemporary reality and

put on a stage. It seems to me, in theater, we need to scavenge,

quite assiduously from our contemporary worlds, if we want to

remain pertinent. In this age of technology, of mind-boggling

deterioration of nature and of post-modern advertising, what are

the languages? I think, wow, so much content comes to mind: everything

from billboards, to words on discarded candy wrappers, television,

especially the sort of interstitial bits in television, what happens

between the big splashy numbers. I find infomercials endlessly

revealing and hilarious and who knows, maybe the natural world

is returning to consciousness again? What do polar bears sound

and look like as they drown? What did Hurricane Katrina look and

sound and feel like?

As

for form, well, I gave my last piece, Tale of 2 Cities,

the structure of a DJ mix, in an effort to reflect the kind of

form I think people are receiving and synthesizing their world

in. The DJ samples fragments from all over, and keeps a beat under

it and repeating melodies that tie it all together. The DJ makes

the fragmented and isolated world whole, or at least something

you can dance to. I tried to do that with dramatic and literary

tropes as my samples: lyric laments, old newspaper articles, lonely

e-mails, interrogations, etc. We have to look at the forms we

actually communicate in and respond to. Little portable screens,

little bitty phones, blogs, group e-mails, video games. There

already seems this urge on the part of video game aficionados,

an incipient movement, to make the games real. To play them out

in the world of the flesh. This sounds on the face of it kind

of creepy and sinister but it could have some brilliant theatrical

results. I do think there's a basic human need to see stuff acted

out, live and in the flesh. Arte con carne, as it were.

theater artists need to have fun with that, go find the new audience.

As

for form, well, I gave my last piece, Tale of 2 Cities,

the structure of a DJ mix, in an effort to reflect the kind of

form I think people are receiving and synthesizing their world

in. The DJ samples fragments from all over, and keeps a beat under

it and repeating melodies that tie it all together. The DJ makes

the fragmented and isolated world whole, or at least something

you can dance to. I tried to do that with dramatic and literary

tropes as my samples: lyric laments, old newspaper articles, lonely

e-mails, interrogations, etc. We have to look at the forms we

actually communicate in and respond to. Little portable screens,

little bitty phones, blogs, group e-mails, video games. There

already seems this urge on the part of video game aficionados,

an incipient movement, to make the games real. To play them out

in the world of the flesh. This sounds on the face of it kind

of creepy and sinister but it could have some brilliant theatrical

results. I do think there's a basic human need to see stuff acted

out, live and in the flesh. Arte con carne, as it were.

theater artists need to have fun with that, go find the new audience.

CS: What critics have

started calling "post-dramatic theater" has managed

to make an art of the current flesh, reflective of the fragmented,

disjointed lives we lead and the connective strands that join

us together. Why do you think the post-dramatic form hasn't found

its way as prominently into the U.S. theater vernacular as it

has in Europe?

HW: Money. There's a huge

amount of support here in the USA for dramatic storytelling. Movies,

TV and all that trickles down to theater, especially as so many

plays and playwrights are auditioning to be in TV or movies anyway.

And it is done brilliantly. America is at the top of this art

form of witty, wry, engrossing, socially engaged yarns. Theater

is often a sort of subsidiary art form, a lesser form that fertilizes

the apex of the form which is TV and movies. In Europe. there's

enormous support for theater to keep evolving. So, it has. And

there's a much richer history of theater as a total, elaborately

sensual art form. But in America's defense, we like drama. We're

a dramatic nation. We're self-dramatizing. We like big, noble

ideas and that's a good thing in some ways, though it can be dangerous

and phony, but there's something very hopeful and romantic about

it, earthy even, that I like.

I feel that I humbly follow in the footsteps

of American writers and gatherers such as John Dos Passos, Steinbeck,

Zora Neale Hurston, Imogen Cunningham, all of whom, with their

disparate and glorious talents, had in common that they were acute

believers in the cumulative eloquence of individuals' life experience.

There's a deep extravagance in taking the time to collect and

cull these voices, whether fictional or documentary, and there

is perhaps something almost taboo or faux-pas, anyway, about taking

that time to sift through and listen. Although my work is entertaining

and dramatic, often even whimsical and melodramatic, there's also

a weird anti-dramatic quality to it. The joy of just hanging out

in the little ebbs and flows of incidental people and their conversations.

There's a luxury in spending a stretch of time with characters.

Instead of insulated television time why not communal time in

a theater? It relates to what Jane Jacobs defined as what makes

city neighborhoods unique: they're about unplanned human interaction,

the alchemy of accidental connection with strangers, and to get

that sort of deeply human, off-the-cuff kind of experience, you

have to be willing to hang out for awhile, to let the unexpected

unfold.

CS: Your work reaches

for multiple perspectives and revels in contradiction. I have

the feeling that this multiple perspective actually helps you

acquire and mold your stories. Is that true?

HW: I do think the performing

aspect helps me listen and transcribe, because it's oral literature.

If you like. I read a fascinating article in The New Yorker

once about these ancient bards in India who still recite these

epic memorized poems or sagas in verse. These are a thousand years

old at least. Tales passed from one illiterate peasant bard to

the next. Now there are none left who know the complete story

but between them the story is still told. People gather for a

festival and hear one particular saga. It takes 30 days, twelve

hours a day, to tell. Apparently someone once taught one such

bard how to read and write, to facilitate writing these stories

down. He immediately began to lose his memory for them and became

dependent on the written word. I LOVED this fact. There's something

passed from ear and eye to tongue to body that is immediate and

wholistic and which the pen, the technology of writing, can interrupt,

much as the technology of the camera disrupts the transmission

of what happens in live performance. So, I do think I listen a

bit subconsciously as well as deliberately and this can be the

glue that makes my observations and imaginings more complete when

they come out for the first time, either on page or stage. What

I'm trying to describe is an almost instinctive, reflexive ability

which I think EVERYONE has, to sort of instantly record and store

other people's perspectives, but it's something that's gotten

fuzzy and half-forgotten, this channeling, this intuiting. It's

no longer practiced. I guess I'm trying to invent some new contemporary

version of a ritual that would help us synthesize, and conjure

up, who we are and what we want, truly want.

CS: Cultural tourism creeps

into a great deal of new writing for performance, often disguised

as travel. Storytellers and dramatists drop into a culture or

several cultures, use what strikes them, and then move on and

present the work under a veil of ethnographic, empathetic reading,

but the voices and figures used still do not have their say or

presence on stage. I am fascinated and troubled by the proliferation

of cultural tourism (sometimes presented through the lens of commentary

on globalization) that goes un-checked on our stages and performance

spaces, especially with work that takes from the other Americas

and Africa. I wonder how you position yourself in relationship

to travel and being in effect a migrant artist who is also an

L.A.-based artist .

HW: A friend of mine brought

an Armenian woman to see my play Tale of 2 Cities and

there's a one-minute scene where two customers are in a famous

Armenian chicken place in Los Angeles and the man is trying to

impress the woman and talking about a massacre -- a gun attack

-- which occurred in another Armenian chicken place several months

ago. He's just telling her this story to have something shocking

to relish and chat about in line. Then they get their chicken

and the conversation abruptly ends. All of this I overheard verbatim

and it had a resonance for me about how horrific losses become

just lurid, entertaining small talk, how everything can be consumed.

Now the scene is quite funny and one thing that makes it funny

is the spot-on imitation of the sort of no-nonsense, deadpan Armenian

women who work the counter in this particular famous chicken take-out

place. Apparently my friend's Armenian friend was dismayed by

the scene and felt that Armenians only got represented as these

chicken ladies with funny accents.

Now, I would argue that the scene kind

of referenced that there was more to Armenian experience than

this, the echoes of another, discarded story of massacre within

the lurid report of the urban L.A. gunman massacre. I would argue

that the whole play is about the specifics of class and race and

cultures and how as individuals we are both absolute products

of those particularities and also absolutely transcend them, how

these horrific losses and mindless consumings connect and bind,

separate and implode us. But I could completely understand how

that scene might have been, from her perspective, the most cursory

and paltry representation of her culture. I don't know quite how

to position myself other than as a human being with a specific

class and race and cultural heritage and, yes, privilege and then

take it from there by acknowledging those specifics and transcending

them through empathy and imagination. It's like traveling. You

can stay at the stupid resort and go on the guided tours, or you

can meet local people, hang out with them, stay somewhere modest,

try to contribute somehow to the place you're visiting. You're

still an outsider though. Hopefully you find commonality as well

as the delicious exotic. Hopefully you even see something about

their culture they are too close to see and in turn they tell

you something about yours.

CS: There is a spiritual

element in your work -- a strong spiritual communion, sometimes

trance-like -- that is suffused with concrete humor and detail.

How do you seek communion and understanding with an audience?

And have you ever engaged with audiences who have not been in

communion, and how have you bridged the divide?

HW: I pray every day.

I'm serious. I think we have to take faith back from the kooks,

globally. To me, the stage is an altar and all art works are a

form of elaborate prayer, an offering to the awesome, to that-which-is-beyond-articulation,

the unnameable. Art is the repeated attempt and failure to name

God. And that failure is something in itself and an offering to

the ineffable.

In many venues, but especially in Austin,

Texas, I had the pleasure of performing for audiences that were

hugely diverse -- blue-haired Republicans from Abilene, Texas,

together with nose-ringed squatter girls and everything in between

-- and it was my greatest pleasure that the piece, my play What

Ever, had characters with whom there was immediate identification

and recognition and others who repelled and grated so that eventually

the story wove not only the characters together but the audiences.

To create this feeling of community with audiences was the deepest

satisfaction I've ever had as an artist. As for the not-in-communion,

in Galway, Ireland, where I performed for the most blessed, avid

audience imaginable, I came to a climactic scene where my octogenarian

heroine Violet has had her poodle gunned down by an anti-abortion

protestor while she was escorting a girl to get an abortion, and

she tells the comatose poodle about a frightening and life-threatening

back-alley abortion she had as a young woman. Now, suddenly I

realized I was performing the scene for an audience 100% with

me but perhaps fifty percent divided on this moral, religiously

freighted question. I was in a nation where abortion was still

illegal. It was very emotional. Some older people left the house

during the story; one, apparently, even got sick. But they returned

and finished out the piece. I don't know what other art form can

directly address something terribly divisive like that to those

who passionately, sometimes violently disagree, and yet, keep

everyone together in it, listening. Okay, perhaps music, but we

all know music wins hands down as the great bringer-togetherer.

Let's give theater this one.

CS: Are there artists

whose methodologies or way of being in the world you are trying

to pass down? And how?

HW: What I love about

both Hurston and Mark Twain is that they were performers too.

Zora, who was the first anthropologist to collect black American

speech and folk tales, could reportedly hold a party spellbound

for hours as she riffed in her "subect's" voices, embroidering

on the overheard conversations she'd collected. Even those who

despised Zora -- as many of her Marxist peers did -- admitted

that she was endlessly entertaining and riveting, channeling these

voices at parties. And Mark Twain, of course, was some form of

proto-performance artist with his hilarious, prankish and brilliant

extemporaneous lectures, which he performed to sold-out halls

across the USA and in Europe and beyond. I love their celebration

of the American idiom, and their rampant employment of that idiom

for the exercise of their own imagination and erudition. So, there's

that and also, not one particular person, but I think a movement,

a cultural moment I grew up with, then came of age in -- the late

sixties, the seventies, the early 80s -- everyone from Richard

Pryor, whom I was lucky as hell to see at Radio City Music Hall

when I was eighteen, to Ethyl Eichelberger, whom I saw doing her

drag King Leer in a basement place called Eight BC in NYC, back

when East 8th Street between Avenue B and C was about as bombed-out-looking

as Dresden after WWII. There was a whole air of experiment, of

freedom to riff, of riding off a whole MOVEMENT of people, a whole

culture of irreverence and impatience and a belief in the magic

of chance, of exploring the random, and that's quite gone, but

I try to keep it as a beacon, that pure ecstatic avidity. I try

to encourage youngsters to recognize it in themselves and let

it burn, baby, burn.