The Long and the Short of It: An Interview

with Tim Etchells

By Jonathan Kalb

[Tim

Etchells is the artistic director of Forced

Entertainment, an experimental theater group with

a core of six artists, based in Sheffield, England, and founded

in 1984. Forced Entertainment’s pieces are very various,

but they all share a discomfort with theatrical enactment rooted

in fixed characterization and pre-scripted stories, and they all

incorporate time and duration into their subject matter. The following

interview focuses on the series of long pieces called “durationals”

that the group began making in the early 1990s, which last between

six and twenty-four hours and for which the audience are free

to arrive, depart and return at any point. It took place in New

York City on Sept. 8, 2008.]

Jonathan Kalb: Why did

you choose the name Forced Entertainment?

Tim Etchells: In the beginning

we didn't really know what we were doing, or what we were going

to make as a group of people. We met when we were students and

we had made a few performances together, in different combinations.

The idea was, when we finished studying we would start a theater

company that would be called Forced Entertainment. It was the

early to mid 80s, and we wanted a name, something light, that

spoke to the possibility of entertainment but which also raised

questions about it. So right from the beginning there was this

tension in the name, and I think that's what we liked. What's

weird of course is that the name became a kind of miniaturized

manifesto. It has been in some ways very good at describing one

central strand of what we've been interested in.

JK: Can you talk about

how you began making the long pieces you call "durational works"?

How and when did they begin?

TE: The original context

is that in Britain we never fit in very well in the theater community.

That's still a bit the case, really, although now we belong to

a certain little strand of it. But the body of what is called

theater in England rejects us as it would any alien entity. So

when we were younger, and even now, we tended to end up in slightly

off-the-beaten-track festivals that were devoted to slightly odd

theater, stuff from visual art, music, installation, maybe video,

these hybrid frameworks. And one of those was the National Review

of Live Art, which still takes place every year, now in Glasgow.

It was a gathering for the community in the U.K. that made stuff

on the edges of theater, on the edges of dance, on the edges of

visual art--stuff that, well, we don't quite know what it is but

never mind, it's performance of some kind. We went there several

years running in the mid 1980s and either presented work or just

saw stuff, and experiences like that, and in other similar festivals,

made it clear that we had a relationship with performance works

quite apart from theater. The kind of conversations we had with

people working in sound, installation and visual art made us think

more broadly about what we did.

Then

at some point -- 1992 or 1993 -- there was an invitation from

Nikki Milican, who ran the NRLA, to commission a new piece. And

I said, "okay, well, we'd like to make a long performance. We'd

like to make something that's twelve hours long." And she said,

"okay sure, that's exciting, that's fine." Afterwards I talked

to the others and said, "I've sold Nikki a twelve-hour show. Now

we have to figure out what it is…" Something in the work had already

broken, or shifted, evidently.

Then

at some point -- 1992 or 1993 -- there was an invitation from

Nikki Milican, who ran the NRLA, to commission a new piece. And

I said, "okay, well, we'd like to make a long performance. We'd

like to make something that's twelve hours long." And she said,

"okay sure, that's exciting, that's fine." Afterwards I talked

to the others and said, "I've sold Nikki a twelve-hour show. Now

we have to figure out what it is…" Something in the work had already

broken, or shifted, evidently.

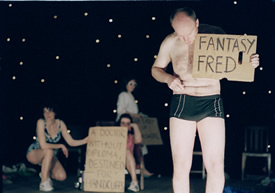

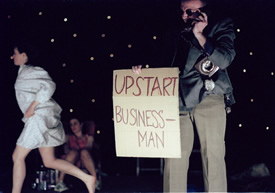

At the time we were rehearsing a theater

piece called Emanuelle Enchanted -- and the seeds of

the long piece were already in that. One section of that performance

involved a rule-based set of interactions, with clothes and cardboard

signs where the actors changed costumes and changed the signs

they held so they "became" different characters. It

was like a kind of endlessly re-combining improv game, a machine

for making stories. In the rehearsals I would often find it very

difficult to stop the action. They would be working with this

set of rules and this set of materials, and I would watch for

twenty minutes and then I'd watch for forty minutes and I'd watch

for fifty minutes, and I would find it very hard to say, "stop

now." Because the progress of the action -- the ongoing ebb and

flow of it -- had an addictive quality. Some weird, ambient and

accumulative aspect of it engaged me. I just didn't want it to

stop.

For Emanuelle Enchanted we were

probably looking for something like a fifteen-minute section based

on these rules using the clothes and the cardboard signs. Doing

fifty minutes or an hour or ninety minutes of it as improv in

the rehearsals seemed crazy, yet I was definitely finding it hard

to stop it. At that point there was a conversation about what

would happen if we made a piece which was just this work

with the signs. We wouldn't cut away from it to something else.

We would simply persist and expand it -- working to see what happened

if we just let the system of rules play itself through in a very

long chunk of time. And that turned into the first durational

piece, 12 a.m. Awake and Looking Down.

JK:

What was the reason why you said to Nikki Milican that you wanted

to do a twelve-hour piece in the first place? What was going through

your head?

JK:

What was the reason why you said to Nikki Milican that you wanted

to do a twelve-hour piece in the first place? What was going through

your head?

TE: It probably came from

excitement about these long improvs, and the possibility of somehow

presenting that work in public. But it also came very much from

our frustrations with theater -- the growing awareness that theater

has a tyrannical economy. Inside an hour and half you have to

make it do something. It has to have shape of a certain kind.

You're always taking people on this journey from A through Z in

this ninety minutes or two hours. And in order to get stuff to

work in that frame, very often we find we have to lean on things

and edit them and tighten them so they make a shape that functions

in that way -- one way or another you're always conforming to

the economy of theater. There's a craft in that and a joy of course

but on the other hand… it certainly makes a change to step away

from it. The nice thing about saying, "we're going to make a twelve-hour

piece and the audience can come and go whenever they want," was

that we released ourselves from this particular theatrical set

of obligations and expectations. When a performance is that long

and with that kind of looser contract with the public, fifty percent

of the things that you worry about as a theater-maker are no longer

worries; they become irrelevant. The world no longer has to be

condensed into this arbitrary time-limit or form.

JK: In one of your writings

you describe a situation in Amsterdam when the audience didn't

come and go. The piece started, went on for a few hours, and people

didn't leave. So you had to think about whether you were repeating

yourself, whether you were giving them something that would satisfy

their dramaturgical expectations. What's your feeling about that?

Are there dramaturgical questions in the longer pieces too?

TE: Yeah, I think that

there are. But I suppose two things. One is that most people don't

stay the whole six hours or twelve hours. Most people's experience

of it is fragmentary, and that does let out some pressure from

this dramatical tyranny. Secondly, if you know that it's twelve

hours long and you can leave, I think your whole relation to the

performance changes. Your expectations are very different. I mean,

you don't walk into a twenty-four-hour-long performance going,

"entertain me!" It's seven o'clock in the morning, or four o'clock

in the morning, the performers there have been going for four

hours already doing something that's reasonably taxing: you know

that the rules are different, and your way of engaging with the

work is different. So yeah, there are systems of expectation and

dramaturgical issues in the longer work but they're different

than the ones that you get in a regular show that starts at eight

o'clock and is finished by nine thirty without an interval. The

longer work has a more fluid economy. Its time is different.

JK: Can you describe the

rule structure for 12 a.m. Awake and Looking Down?

TE:

Okay. There are two sets of clothes rails at the sides with a

whole lot of second-hand clothing on them, and underneath those

are a lot of cardboard signs. They're just cardboard packaging

with names written of about 150 characters. There's a wide range.

Some are made-up figures: "The Hypnotized Girl," "A Stewardess

Forgetting Her Divorce," or "Frank, Drunk." These are the kind

of figures you might see if you're walking in the city and say

to yourself, "oh yeah, The Staggering Man." But alongside these

there are also real figures: Jack Ruby is in there, and Valentina

Tereshkova, the first woman in space. Likewise figures from fiction.

Banquo's Ghost is in there, Lolita, Mad Max. So the catalogue

we are working with presents an odd mix of real, fictitious, and

urban mythological names.

TE:

Okay. There are two sets of clothes rails at the sides with a

whole lot of second-hand clothing on them, and underneath those

are a lot of cardboard signs. They're just cardboard packaging

with names written of about 150 characters. There's a wide range.

Some are made-up figures: "The Hypnotized Girl," "A Stewardess

Forgetting Her Divorce," or "Frank, Drunk." These are the kind

of figures you might see if you're walking in the city and say

to yourself, "oh yeah, The Staggering Man." But alongside these

there are also real figures: Jack Ruby is in there, and Valentina

Tereshkova, the first woman in space. Likewise figures from fiction.

Banquo's Ghost is in there, Lolita, Mad Max. So the catalogue

we are working with presents an odd mix of real, fictitious, and

urban mythological names.

What the performers do over the course

of the piece is choose signs from the stacks of signs, then choose

clothes from the clothes rails, dress themselves, and then present

themselves as if to say, "I am now this person." Meanwhile, another

performer--there are five of them--will take different clothes

and a different sign and present himself or herself as another

person. They don't speak. They present themselves either as static

figures or include a little bit of motion. So maybe "The Hypnotized

Girl" might sway slightly with her eyes raised to the heavens,

or someone playing "Lost Lisa," might grab a coat and sunglasses

and hold the sign, then wander round the space looking like she's

lost. Some of the acting is very demonstrative, very cartoon-like

and simple. Sometimes it looks a little bit more filmic, so you

might get "Frank, Drunk" on a chair at the back of the space,

with Richard staying there with the sign for five minutes, just

swaying slightly. But the other performers contrast him by changing

costumes very fast and grabbing signs and stuff. You can see in

the background that Richard is still there, swaying with his "Frank,

Drunk" thing, but at some point he will break that and go grab

another sign and some different clothes.

This is the basic mechanism of the piece.

I suppose the other rule in it is that you don't much interact

with the other people. So you get these situations where "Elvis

Presley, The Dead Singer" is standing at the front and "A Nine

Year Old Shepherd Boy" comes to stand beside him; there might

be a moment of eye contact or a little look between these two

figures, but that will be it. They don't get into complicated

improv where they join up together to make a story. And I suppose

one of the things that fascinated us when we were making the piece

was the way that these independent fragments of story and character

kind of floated in the space. You had this feeling that there

could be narrative involving "Valentina Tereshkova" and "Jack

Ruby", even though they just glided past each other.  As

they're moving past each other your brain wonders, "what is that?

What happened? What is that?" Then it dissolves again. So we've

talked about this work as a kind of narrative kaleidoscope, an

optical toy where you turn the wheel and the pattern changes.

It's almost a machine for making stories, or throwing up the possibilities

for stories. And we didn't like them to interact too much because

at the point where they did so the machinery stopped. The sense

of endless possibility stopped. You thought, "well now we're deep

in some silly nonsense between Elvis and A Bloke Who's Just Been

Shot," and that's just not very interesting. It's much more interesting

to let the machine continue to operate, to let the combinations

keep moving, and let all the story-making stuff go on in the minds

of the viewer. That's where all of the work is happening.

As

they're moving past each other your brain wonders, "what is that?

What happened? What is that?" Then it dissolves again. So we've

talked about this work as a kind of narrative kaleidoscope, an

optical toy where you turn the wheel and the pattern changes.

It's almost a machine for making stories, or throwing up the possibilities

for stories. And we didn't like them to interact too much because

at the point where they did so the machinery stopped. The sense

of endless possibility stopped. You thought, "well now we're deep

in some silly nonsense between Elvis and A Bloke Who's Just Been

Shot," and that's just not very interesting. It's much more interesting

to let the machine continue to operate, to let the combinations

keep moving, and let all the story-making stuff go on in the minds

of the viewer. That's where all of the work is happening.

JK: How does the piece

move from sequence to sequence?

TE: Basically everybody's

kind of on their own track, constantly finding clothing, finding

a cardboard sign, presenting themselves for as long or as short

a time as they like, and then when they're finished they go and

get another one. Meanwhile, the other performers in the space

are doing the same thing. It's fluid, organic, interwoven.

JK: Is it always the same

in each performance?

TE: No it's totally different.

Improvised in real time. They don't know each other's tracks.

That's the case with all of the long pieces we've done. With one

exception, Marathon Lexicon, they're never fixed. The

long works are basically rule structures inside which the performers

are free to operate, making real decisions about what they do

next in reaction to what the others are doing, what the audience

is doing, and what they feel like.

JK: So there's no way

to talk about development in them, because it would be a different

development in each performance?

TE:

Yeah, that's interesting. The durationals find a new shape each

time they are presented, within the parameters that are possible.

We're not really interested in them as ways to create outrageous

narrative or developmental arcs though! They tend to be quite

flat in that sense -- to travel is better than to arrive kind

of thing. You might best think of them as landscapes of endless

variation… but in which no change is permanent. It's flux.

TE:

Yeah, that's interesting. The durationals find a new shape each

time they are presented, within the parameters that are possible.

We're not really interested in them as ways to create outrageous

narrative or developmental arcs though! They tend to be quite

flat in that sense -- to travel is better than to arrive kind

of thing. You might best think of them as landscapes of endless

variation… but in which no change is permanent. It's flux.

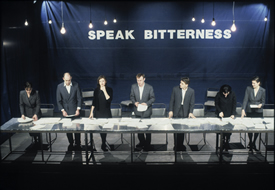

One aspect of shape that is predictable

or recurrent though are physiological or other rhythms. For instance,

if a perfomance like Speak Bitterness or And On The

Thousandth Night... is six hours long, the performers get

tired and there is usually a certain hysteria by hour five. You

are generally trying too hard in hour one. So you can say certain

things about the shape and rhythm of those pieces, but it's not

written or dramatically forced. What's allowed to happen in all

of the durationals is that the performers step into the space,

begin, and then play, and then at the end it's finished. In a

way it's like football, or any sport: you know what the rules

are, you know who the players are, but you don't know what will

transpire inside the set of rules.  Anyway,

we found these durational works tremendously liberating because

they confirmed for us that you don't have to give something new

every ten minutes in a theater piece -- simple structures can

go a long way. In the 1980s, when we started making work, we had

this rather pop-video-driven idea that everything should change

all the time. New things needed to happen every minute.

Anyway,

we found these durational works tremendously liberating because

they confirmed for us that you don't have to give something new

every ten minutes in a theater piece -- simple structures can

go a long way. In the 1980s, when we started making work, we had

this rather pop-video-driven idea that everything should change

all the time. New things needed to happen every minute.

JK: You once said that

channel-surfing was the model for your work up to a certain point,

and then you got tired of it and discarded it.

TE: Yes. But the way it

seems now is that there are -- to put it crudely -- two approaches

to the problem of theater for us. One is to try to put more into

it than is sensible: fill it, overload it, and see if we can blow

it up. The other is to starve it, take as much out of it as we

possibly can. So at the too-much end you get shows like Club

of No Regrets or Bloody Mess, which is ten people,

with everybody on a separate mission or track. It borders on incoherence,

and has this simultaneous, multi-tasking, channel-hopping thing.

On the other hand, you get something like Dirty Work,

which was made a few years before that, or other pieces we've

made more recently, where it's an hour and twenty minutes, two

people, and they sit and talk, describing a theater show which

doesn't happen. That's all it is. So there's a starvation diet

on one hand and an excess diet on the other. Crudely, those are

the bipolar attractions of our group. We seem to swing madly between

the one and the other.

JK:

You've spoken about your personal impulses. I wonder, though,

whether the durational works were also responding to anything

in the historical moment of the early 1990s.

JK:

You've spoken about your personal impulses. I wonder, though,

whether the durational works were also responding to anything

in the historical moment of the early 1990s.

TE: Well, I do think this

work of long duration challenges patterns of consumption. If people

are used to the idea that what they're going go watch will last

an hour and half and in that time it will serve them up something

nicely packaged with a bow on top, then making something that

is sprawling in time makes out-of-the-ordinary and difficult demands.

I mean, if you want to see the whole of a twelve-hour piece, that

makes an unreasonable demand. Engaging with the time-frame knocks

you into a different kind of relationship to the work. You can't

go in with the attitude, "Okay, entertain me." It's a very different

contract. And for some people that has not been possible. The

work is not of interest to them. But for other people it has really

opened a door. They could find that this work spoke to them more

than other things.

I think a lot of what we do is look for

ways to make intense connections to the audience. At the time

we started making the durationals it seemed possible to make a

different kind of connection that way than we could with the ninety-minute

theater work. For sure, we tried different strategies in the theater

work. But it seemed to me that stretching the time, making a different

kind of social demand on the audience, a demand that wasn't necessarily

sensible or comprehensible, was a leap forward. Perhaps it's too

much to talk about these things being against commodification,

because they're usually ticketed and people have to pay to go

in, but they are against commodification in the sense

that they are hard to grasp. I mean, you can't just pick the event

up and say, "that's what that was," because it is different every

time and you can't really even see it as a whole. The event slips

through your fingers as you try to pick it up, and that seems

really important. Politically, it's no accident that these pieces

began on the back of the 80s and rolling into the 90s, which was

an intensely commodified time. One of our responses to the culture

of channel-hopping, the culture of packaging and presentation,

the short, the sharp and the quick, quick, quick, was to slow

down. Let's just take twelve hours over something, and see who

stays.

JK:

There were no tickets sold for Quizoola! in Portland,

Oregon, the durational piece you did at the TBA Festival. People

could come and go at will.

JK:

There were no tickets sold for Quizoola! in Portland,

Oregon, the durational piece you did at the TBA Festival. People

could come and go at will.

TE: Yes, that was good.

It wasn't difficult there at all because we've worked with the

curator, Mark Russell, before and he knows Quizoola!

and its requirements. But it's interesting that the durational

things do tend to pose a challenge to institutions. The logistics

of explaining to people how to present these works is not simple.

Sometimes people say, "we would like to present Quizoola!"

And you ask, "um, do you actually understand what that means?"

I mean, it's not so complicated but actually getting people to

understand the demands of this unwieldy object, in terms of space

or ticketing or time, or allowing the audience to come and go,

is not so straightforward.

JK: How large are the

audiences, usually?

TE: It varies. They can't

be too big for Quizoola! or 12am because of

the kinds of spaces they tend to be played in. And on the

Thousandth Night, our durational storytelling piece, plays

in more conventional theatre spaces and so it's not uncommon that

we have an audience of 150 or 200 people, but depending on what

time of night we start, we can be down to sixty or thirty for

a while before it builds up again for the end. These kind of variations

in the numbers are interesting because they affect the dramatic

situation -- playing to a small crowd allows you to do different

things as a performer. When we did the twenty-four-hour performance

Who Can Sing A Song To Unfrighten Me?, there were times

in the middle of the nght when we would be playing for just a

handful of people in an auditorium for five or six hundred. There

was something incredibly intimate and strange about that.

And

actually, even with the largest audiences for the durational work,

there's always a sense of being here in the same room, being all

a part of this strange event. I think what's intriguing to me

about them is that heightened sense of, "well here we all are

then." In the long pieces, as performers, you can very often see

the audience. People are watching and you get to know them. You

get to see that that guy's falling asleep, or that one's laughing

all the time, or that one looks engaged. You don't talk to them

but in a way you make friends with people. So there's a weird

heightening of the liveness thing.

And

actually, even with the largest audiences for the durational work,

there's always a sense of being here in the same room, being all

a part of this strange event. I think what's intriguing to me

about them is that heightened sense of, "well here we all are

then." In the long pieces, as performers, you can very often see

the audience. People are watching and you get to know them. You

get to see that that guy's falling asleep, or that one's laughing

all the time, or that one looks engaged. You don't talk to them

but in a way you make friends with people. So there's a weird

heightening of the liveness thing.

JK: This is perhaps more

of a theater question than you might like, but what would you

say if I asked what was at stake in the durational performances?

TE: I think what's possible

in those pieces is that you, as an audience member, encounter

those other people, the performers, in an extraordinarily complicated

and intimate way. I think there's something very valuable about

that. I think one of the things performance can do is sensitize

you to time. And it can sensitize you to other people. In performance

perhaps more than in other things, you feel and understand time,

and feel and understand other people as decision-makers, as complicated,

contradicted, frail, vulnerable, funny beings. And so much of

the world is made to hide or deny these things. It often seems

as if just to function in the world you have to not engage. The

way the society is structured, it doesn't really want you to do

that. Most of what capitalism throws out is barriers and division.

And I think performance, and especially the long pieces, have

a capacity to open connection and open sensitivity to other people.

That's what's at stake.

------------------

All photos copyright Hugo

Glendinning.