Spy

Trails

Spy

Trails

By Jonathan Kalb

Democracy

By Michael Frayn

Brooks Atkinson Theatre

256 W. 47th St.

Box office: (212) 307-4100

In a program note to his new play, Democracy,

the British playwright Michael Frayn laments that "The only part

of German history that seems to arouse much interest abroad is

the Nazi period. The half-century or so which has followed Germany's

awakening from that sick dream is thought to be a time of peaceful

but dull respectability." Germany's postwar prosperity, peacefulness,

and "even that supposed dullness," writes Frayn, "represent an

achievement at which I never cease to marvel or to be moved,"

and he set out to write a major play about that.

It was a noble ambition. At a time when

democracy seems to be on the wane in the United States and much

of the world, Frayn sought to spotlight what he saw as an instance

of marvelous waxing in the wake of utter desolation and moral

degradation. Furthermore, since that degradation had partly to

do with human institutions gone awry, he wanted to look closely

at another kind of institution that did a better job addressing

the "reconciliation of irreconcilable views." There was something

about the very humdrum nature of coalition politics, mirroring

the bureaucratic tendencies of Germans, that spurred his interest.

Trouble is, dullness and respectability

have never been the best fuels to ignite a major play, so Frayn

found a sexier focus in the most colorful German political figure

of the period, Willy Brandt. Even a brief sketch of Brandt's eventful

life will explain why this new focus immediately overwhelmed all

previous intentions.

Born Herbert Frahm and active in the Socialist

Youth Movement from his early teens, Brandt left Germany in 1933

to escape the Nazis and never again worked under his given name.

During exile, he did resistance work in Norway and Sweden under

various pseudonyms, at one point returning to Berlin disguised

as a Norwegian. He was Mayor of West Berlin when the Berlin Wall

went up. In 1969, he became the first German Chancellor from the

left in forty years, and under his Eastern Policy (Ostpolitik)

he cooled tensions with the Soviets, Poland and the GDR by signing

previously unthinkable cooperation agreements--for which many

branded him a traitor despite his winning the Nobel Peace Prize.

In 1974, he resigned as Chancellor after his personal assistant,

GŁnter Guillaume, was unmasked as an East German spy. Dramatizing

dull respectability while telling this story well was a puzzle

even the ingenious Frayn could not solve.

Democracy--which opened at the

Brooks Atkinson Theatre in New York in November following a sold-out

run with a different cast at the National Theatre in London--is

a sort of companion piece to Copenhagen, Frayn's play

about a secret wartime meeting of two nuclear physicists that

ran for ten months on Broadway in 2000-01. Both works are peculiar

hybrids, products of prodigious research and copious historical

documentation that ultimately spurn the rigors of docudrama in

favor of ruminations on uncertainty. Frayn's absorbing 1999 novel

Headlong plays a similar game, inviting readers to follow

an elaborate scholarly argument about Bruegel that turns out to

be useless to the characters. Frayn, who was trained as a philosopher

at Cambridge, seems to be taking a philosophical attitude toward

research of late, indulging in it in order to jettison it as a

narrative shill.

Democracy spends most of its time--two

hours and forty minutes, in Michael Blakemore's production--recounting

the highlights of Brandt's Chancellorship. On a spare, white,

modernist, two-level office set whose walls are arrayed with obsessively

orderly rows of color-coded files (design by Peter J. Davison),

Brandt is seen: dealing with a half dozen gray-suited party colleagues

(including the hyper-ambitious Helmut Schmidt, who itches to displace

him); celebrating the triumph of his Ostpolitik; surviving

a no-confidence vote and a second national election; responding

to radical terrorism; kneeling at the memorial to the murdered

Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto, and much, much more.

This thicket of historical minutiae is

played off against the more personal story of Brandt's private

afflictions (depression, alcoholism, indecision) and his relationship

with the non-descript Guillaume, who boasts to his Stasi handler,

Arno Kretschmann (Michael Cumpsty) that he's a "Hatstand. No one

notices it." Along with Kretschmann, Guillaume acts as narrator,

standing both inside and outside the action. Played by Richard

Thomas with a padded belly and a jovial servility that irritates

but never quite justifies Brandt's description of him as "greasy,"

Guillaume meets with Kretschmann at a cafť table to the side and

speaks often over his shoulder to him while acting in scenes with

his office colleagues. Kretschmann sometimes answers questions

that Guillaume puts to others, or fills in background no one has

asked for.

Brecht would have admired this device.

Clever and efficient, it's one of those lively approaches to keeping

multiple balls in the air for which Frayn is rightly admired,

and it has the provocative effect of forcing the audience to consider

the Stasi viewpoint as normative. Guillaume is given enough emotional

latitude to appreciate the romance and drama of electoral politics

("Never mind football! Try parliamentary democracy!") but Kretschmann

toes the ideological line and provides a Martian-like perch for

viewing the Western system: "Democracy, GŁnter! Sixty million

separate selves, rolling about the ship like loose cargo in a

storm."

When Brandt's grizzled SPD colleague Herbert

Wehner (cunningly played by Robert Prosky) comes out with cynical

quips like, "the more [democracy] you dare, the tighter the grip

you have to keep on it," it's easy to lose track of who the good

guys and bad guys are. (In his memoirs, the real Brandt suggested

that Wehner had conspired in his downfall.) In the end, Brandt's

Ostpolitik is seen as having hastened the end of the

Cold War, with Guillaume sharing credit because his reports convinced

the GDR leaders to trust Brandt. The fall of the Berlin Wall prompts

the evening's sole technical coup de theater.

Frayn's boldest conception in Democracy

was to imagine the extraordinary ordinariness of representative

government as a dramatic spectacle, filling us with wonder at

the skin-of-our-teeth miracle that such a system survives at all,

anywhere, given the constant doubts and attacks on it from without

and within. As in all his serious plays, however, his deeper purpose

here is to dramatize the complex, divided nature of human beings.

The complications, negotiations, compromises and infighting of

representative government are used as a figure for social life.

"I think human beings are kind of democracies within themselves,"

Frayn said in a recent interview.

Thus, the fictional Brandt is not only

attacked from all sides over public policy but also haunted by

the plurality of masks and aliases he has adopted. Guillaume is

not only spying on him but also a little in love with him. Horst

Ehmke, a loyal aide (affably played by Richard Masur) whom Brandt

carelessly pushes away, puts the theme this way: "Life's such

a tangle . . . Everyone looking at everyone else. Everyone seeing

something different. Everyone trying to guess what everyone else

is seeing. It's such an endless shifting unreliable indecipherable

unanalysable mess!"

For all its probing and cleverness, however,

Democracy isn't Frayn's happiest conception for accommodating

his characteristic theme. His ambivalent obsession with research

got in the way this time. His 1984 play Benefactors is,

to my knowledge, Frayn's most elegant use of this theme because

it dwells on the uncertain "goodness" of a controversial public

works project by following the changing private relations within

and between two couples. In Copenhagen, the balancing

trick was harder because he set himself the task of teaching spectators

the basics of quantum mechanics. He managed things there, though,

by limiting the cast to three characters who described themselves

as ghosts and compared themselves to subatomic particles, circling

one another in a wonderfully ambiguous human-rights-court-cum-electron-cloud.

Somehow, all their talk about particle attraction, repulsion,

and spin was easily understood as passionate, metaphorical references

to trust, friendship, love, and survival.

Democracy,

by contrast, takes place in a cold, sterile office and has ten

characters who all come off as too thinly drawn for anything but

straight docudrama. It's far less effective at intertwining its

human stories with philosophical aims. Guillaume's editorializing

as narrator, for instance, signals that he's the play's real lead,

yet his role can't bear that responsibility with its nebishy persona

and diminutive emotional compass. He's split internally because

of his infatuation with Brandt, but it's not a profound split,

nothing like the Iago-like monumental grudge he'd need to sustain

focus over Brandt. Tellingly, neither he nor Kretschmann have

much to say in the way of compelling description of the GDR, its

values, or its society. Both speak about "home" in generalities

and without conviction.

Democracy,

by contrast, takes place in a cold, sterile office and has ten

characters who all come off as too thinly drawn for anything but

straight docudrama. It's far less effective at intertwining its

human stories with philosophical aims. Guillaume's editorializing

as narrator, for instance, signals that he's the play's real lead,

yet his role can't bear that responsibility with its nebishy persona

and diminutive emotional compass. He's split internally because

of his infatuation with Brandt, but it's not a profound split,

nothing like the Iago-like monumental grudge he'd need to sustain

focus over Brandt. Tellingly, neither he nor Kretschmann have

much to say in the way of compelling description of the GDR, its

values, or its society. Both speak about "home" in generalities

and without conviction.

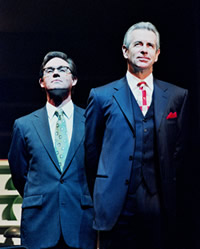

This muddied focus puts the actor playing

Brandt in an awkward position, and indeed James Naughton has taken

considerable flak from reviewers for his starchy, patrician portrayal

of Brandt (too Kerryesque, it seems, whereas the real Brandt was

more expansive, like Clinton). Naughton deserves credit, though,

for fleshing out a character that Frayn left emotionally sketchy.

Whether drinking and brooding in a lone armchair on the set's

upper level, or standing beside Guillaume exchanging rather ordinary

thoughts about why both can't help leering at women, he brings

psychological cogency, complexity and gravity to many moments

where the script leaves him blanks.

There is one scene late in the action that

suggests what Democracy might have been had its characters

been given more thoroughly imagined inner lives. The restrained

Brandt, having been told that Guillaume is under suspicion, finds

himself suddenly flush with appreciation of human complexity:

"The merest possibility that Guillaume's not what he seems makes

him infinitely more tolerable." Brandt then agrees (so that Guillaume

can be kept under observation) to go on vacation to Norway with

him and their two families, and there the spy-game becomes double-edged

and the dialogue spiced with refreshing irony.

Guillaume: Freedom

. . . That's what's so relaxing about this place, Chief. You

can leave all the doors unlocked and let the kids run wild.

Brandt: You know why that is, GŁnter?

Guillaume: Because the whole area's been sealed

off by the local police.

Brandt: Our own little police state to make

you feel at home.

This circumstance adds present-tense excitement

to the historical reports of Brandt's wartime spying, and it wipes

the smile briefly off the face of the play's smug, panoptical

narrator: a few more scenes like this would've done a lot to lift

Democracy more securely above its factual quicksands.

These problems aside, though, I found myself

grateful that Democracy had arrived on Broadway amid

a dreadful election season. A strong narration of Brandt's political

fall holds invaluable lessons for the present moment, when millions

are questioning whether it's even possible for a gentle, compassionate,

sophisticated, worldly, secular, enlightened, peacemaking leadership

to prevail again over a simplistically belligerent, hawkish, deliberately

narrow-minded, ideologically blinkered leadership that plays cynically

on people's fears and base instincts. Regardless whether you buy

Frayn's argument about Brandt and the Cold War, any drama that

prompts sober reflection on this question at this moment has earned

a respected place in American culture.