Silent Suppression as Feminist

Expression: Fanny Burney's The Witlings

By Johnna Adams

The role of the professional female playwright

was still very much a work in progress in the English theatre

during the late 18th Century. As a novice playwright, established

novelist Frances "Fanny" Burney wanted to create a comic masterpiece

for the stage--an aspiration she referred to in her journals as

her "golden dream." [1] But there were no models for her to look

to for the type of satirical, female character-driven work she

wanted to create. In the absence of any guidance, she created

characters that were biting, satirical portraits of other women

in a work called The Witlings. When she realized, however,

that this play might damage the work done by the increasingly

powerful Bluestocking Circle (which she admired) and in particular

its famous salon hostess, Lady Elizabeth Montagu, she made the

decision to suppress her own play. The decision would haunt her

for the rest of her life, and she would never regain the writing

momentum or easy opportunity for production that she gave up by

abandoning this first play. Nevertheless, her choice, made at

a time when female playwrights were not looking critically at

their work to evaluate how it might be perceived by other women,

portray other women, or affect the public perception of women

as literary authorities, makes a significant feminist statement.

A prominent novelist by age 26, Burney

is generally considered to be "the most esteemed woman novelist

of the period" (Janet Todd). [2] She is almost as well-known for

her detailed diaries and personal correspondence. During her extraordinary

life, she served as Queen Charlotte's lady-in-waiting; was kissed

and chased by mad King George III during a fit of dementia; watched

Napoleon marshal troops in Paris to invade England; heard the

guns of Waterloo and watched its casualties clog the streets and

homes of Brussels; suffered a brutal mastectomy without anesthesia;

and witnessed Queen Victoria's coronation. [3]

But before all of these adventures, when

young Burney was first introduced to literary society, she suffered

from intense and mortifying shyness. Praise for her first novel,

Evelina, left her feeling uncomfortable and on occasion,

in her own words, "seriously urgent and really frightened." [4]

In 1779, during a visit with Mrs. Hester

Thrale, a distinguished hostess in literary circles whose Streatham

Park home served as Samuel Johnson's summer retreat, the idea

was first suggested (by Thrale) that the timid Burney explore

a career as a dramatist. Burney recalled Thrale's words:

--you must set about a Comedy, --and

set about it openly; it is the true style of writing for you,

--but you must give up all these fears and shyness, --you must

do it without any disadvantages. [5]

Taking this advice to heart, Burney secretly

began work on a play influenced by Thrale and the circle of literary

minds that gathered for her dinners, including Johnson and members

of the well-known Literary Club of Samuel Johnson. [6] She began

writing this play in greater earnest with the encouragement of

Drury Lane's artistic director, Richard Sheridan. When asked if

he would consider producing a play of Burney's without reading

it in January of 1779, Sheridan replied "Yes! . . . . and make

her a Bow and my best Thanks into the Bargain!" [7] Burney's reaction,

recorded in a letter describing the meeting with Sheridan, was

ecstatic,

Consider Mr. Sheridan as an Author and

a Manager, and really this conduct appears to me at once generous

and uncommon. . . . And now . . . -- if I should attempt the

stage,-- I think I may be fairly acquitted of presumption, and

however I may fail,-- that I was strongly pressed to try by

. . . . Mr. Sheridan,-- the most successful and powerful of

all Dramatic living Authors,-- will abundantly excuse my temerity.

[8]

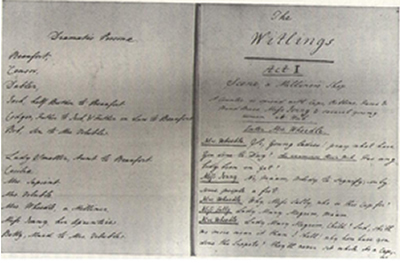

Burney's first play, The Witlings,

was written in May of 1779, less than five months after Sheridan's

invitation. It is a social satire in which Lady Smatter, the patron

of a literary salon known as the Esprit Party, forbids her dependent

nephew, Beaufort, to marry his fiancée Cecilia, also Smatter's

dependent, when Cecilia loses all of her fortune through the mismanagement

of an incompetent banker. Eventually, Beaufort's friend Censor,

a respected intellect of the day, resolves the situation, extorting

Smatter's blessing on the marriage by threatening to publish a

vicious verse lampoon he has written about her greed and ignorance.

Read today, the play doesn't seem especially

damaging to the credibility of women's literary contributions,

though it does contain unflattering female stereotypes. A closer

look at the satire, however, reveals that Burney has chosen as

a principal target the leading promoter of female writers of the

day, Lady Elizabeth Montagu, and directed her sharp disdain toward

the establishment of the Bluestocking Circle (the "Blues"). Burney

was a peripheral figure associated with the Blues, a group of

intellectual women (some men as well) who established salons for

critical debate around literary figures and forms. Of the Blues,

Deborah Heller said the organization provided "an instance where

women appear to be full and active participants in the public

sphere." [9] Not only were the Blues the foremost institution

promoting female literary merit, both as authors and critics;

Heller points out that "as organizers of the English literary

salon, they could be said to be co-architects of the public sphere."

[10] Sue-Ellen Case also observes that salons like the one created

by the Blues served as "theaters of personal dialogue" and were

an important chapter in theater history. [11]

Although privately complimentary toward

Lady Montagu and the Blues, Burney began to hear them ridiculed

at Thrale's informal, semi-public dinner parties and to be swayed

by the opinions of Thrale's important guests. [12] Samuel Johnson

was an enthusiastic fan of Burney's Evelina and maintained

that the novel was better than any of Henry Fielding's novels.

[13] During her visits at Streatham, he was extremely forthcoming

with her about his opinion of Montagu. Although they were on speaking

terms, Montagu's criticism of Johnson's Preface to Shakespeare

(1765) in her own essay An Essay on the Writings and Genius

of Shakespeare (1769) had caused a rift in their relationship

that left him scornful of the prominent Blue. [14]

In his 1776 A Dictionary of the English

Language, Johnson defines "witling" to mean, "a

petty pretender to wit," and this would aptly describe his opinion

of Lady Montagu. In a letter written in 1778, Burney recounts

a conversation between herself, Thrale and Johnson in which Mrs.

Thrale announced that Lady Montagu would be joining them for dinner

the next evening. Johnson assumed a "countenance strongly expressive

of inward fun," then turned to Burney and said,

Down with her, Burney! -- down with

her! -- spare her not! -- attack her, fight her, and down with

her at once! You are a rising wit, and she is at the top; and

when I was beginning the world, and was nothing and nobody,

the joy of my life was to fire at all the established wits!

. . . when I was new, to vanquish the great ones was all the

delight of my poor little dear soul! So at her, Burney -- at

her, and down with her! [15]

As if feeling somewhat ashamed of recording

this, Burney immediately qualifies it by saying, "Mrs. Montagu

is in very great estimation here, even with Dr. Johnson himself,

when others do not praise her improperly. Mrs. Thrale ranks her

as the first of women in the literary way." [16] Even this apology

admits partiality to Johnson's opinion as she insists there is

"proper" praise for Montagu and "improper" praise and Johnson

could be trusted to distinguish between them.

Johnson's attempt to draw a comparison

between himself as a young writer, attacking the reputations of

leading male intellects of the day, and young Burney launching

a similar attack on prominent female intellects shows Johnson's

lack of understanding about the position of a young female writer

in late 18th-century England. His opinion doesn't allow for the

fact that women's literary relationships of the time were, by

necessity as much as by natural feminine inclination, collaborative

and communal. His world view rejects the Blues's ideal conception

of a literary society founded on principles (in Deborah Heller's

words) of "a social bond consisting in shared speech or communication."

[17] Instead, he persuades Burney that she is in a competitive

relationship with her most powerful female patron and advocate.

Johnson's influence can be seen in an account

of a dinner party at Streatham in one of Burney's letters. She

observed, "The Bishop [of Chester] waited for Mrs. Thrale to speak,

Mrs. Thrale for the Bishop; so neither of them spoke at all. Mrs.

Montagu cared not a fig, as long a she spoke herself, and so harangued

away." [18] Montagu was conscious of this type of ridicule, which

often centered on her intense personality and involved disparaging

comments about her wit. Deborah Heller notes that Montagu's conversation

was considered "masculine" and was "marked by a certain amount

of aggressiveness." [19] Montagu wrote to a new acquaintance after

making a bad first impression,

. . . you had heard I set up for a wit,

and people of real merit and sense hate to converse with witlings;

as rich merchant-ships dread to engage with privateers: they

may receive damage and can get nothing but dry blows. [20]

If Montagu was in the habit of referring

to herself mockingly as a "witling" that may have been an inspiration

for Burney's title.

Similarities between Lady Smatter and Lady

Montagu are glaringly obvious. Montagu, like Smatter, had a dependent

nephew when the play was written. [21] Barbara Darby points out

that Montagu's only notable work of literary criticism was her

Shakespearean analysis, and Lady Smatter makes a rather obvious

smear on that accomplishment with her line in Act IV of The

Witlings saying Shakespeare, "is too common; every

body [sic] can speak well of Shakespeare!" [22] As the character

of Lady Smatter is the wealthiest and most influential of the

Esprit Group in The Witlings, Lady Montagu was the wealthiest

and most influential member of the Blues. She maintained control

of her own family businesses after her husband's death and ran

them with diligent attention. [23]

Burney's relationship to money is clearly

expressed in her writing, particularly her characterization of

Cecilia in The Witlings, and it is a possible partial

explanation for her resentment toward Montagu. Burney wrote a

novel called Cecilia shortly after the suppression of

her play in which the title character is clearly a more fleshed

out version of The Witlings's Cecilia. The Cecilia in

Cecilia and Evelina in Evelina both possess

fortunes by inheritance that they did not earn. Like The Witlings's

Cecilia, they lose everything through the incompetent administration

of one, or a series of, men. In Burney's writing, women did not

manage money, especially not on the large scale that Montagu managed

her family fortune. In her work, and decidedly in The Witlings,

Burney vilifies the rich. Montagu was actively involved in improving

labor practices at her family coal mines, investing intelligently

in land management and financial planning for other family members.

[24] But Burney's parody reduced the idea of a wealthy woman to

a jealous, superior, greedy and self-satisfying caricature.

Disappointingly, and in contrast to the

Blues's work to expand the notion of women's roles and capabilities,

all of the The Witlings's female characters are versions

of the classic female stereotypes described by Case as "the Bitch,

the Witch, the Vamp and the Virgin/Goddess." [25] Lady Smatter

fulfills the "Witch" role and also presents a stereotype not discussed

directly by Case, but traceable to Aristotle's Poetics,

which states, "it is possible for a character to be brave, but

it is not appropriate to a woman to be brave or clever." [26]

The "not clever" female stereotype can be referred to as "the

Air-Head." Lady Smatter's constant misquoting of famous poets

is a classic example of the stereotypical Air-Head female who

apes male cleverness but is an obvious fraud. Censor says of her

in Act III:

Heavens, that a woman whose utmost natural

capacity will hardly enable her to understand The History

of Tom Thumb, and whose comprehensive faculties would be

absolutely baffled by the Lives of the Seven Champions of

Christendom, should dare blaspheme the names of our noblest

poets with words that convey no ideas, and sentences of which

the sound listens in vain for the sense! [27]

Satirically charging the greatest of the

Blues with "blaspheming" the poets and "having no ideas" undermined

the Bluestocking Circle's ambitions to champion women's educational

and literary potential.

The lead character Cecilia is firmly a

Virgin/Goddess, but she also fulfills another female stereotype

very common in Burney's work, "the Victim." She is made penniless

by the banker who loses her legacy and is then thrown out of Lady

Smatter's house for being destitute and, therefore, an undesirable

match for her nephew. Ultimately, Cecilia's salvation comes at

the hands of men through the defeat and humiliation of another

woman.

In this play, the pretentious, self-promoting

female who wields masculine powers of wealth and social influence

(Lady Smatter) must be destroyed so that the Virgin/Goddess (Cecilia)

can fulfill her patriarchal purpose and marry Beaufort at the

conclusion of the play. If you insert Lady Montagu into the role

of Lady Smatter in this comparison, then the message is clear:

the Bluestockings with their pretentious ambitions to wield masculine-type

influence in the world of literature must be thrown down so that

the patriarchal monopoly on literary affairs can be maintained.

Burney's eyes were opened to the potentially

damaging effect of her satire by her father, Dr. Charles Burney,

and a clergyman who was a longtime friend of the Burney family,

Samuel Crisp. Crisp wrote her a letter informing her that the

subject she chose for her play was "invidious and cruel," and

would be perceived as holding certain people "up to public Ridicule."

[28] Burney's reply, in a letter to her father dated August 13,

1779, indicated that she would suppress the play not based on

petty individual errors but because "the general effect of the

Whole . . . has so terribly failed." [29]

Darby suggests that the sole reason Burney

suppressed the piece was the disapproval of her father and Crisp

. [30] But her father's commitment to the suppression of the play

was not absolute. Burney wrote to Crisp in 1780 that since her

play was "settled in its silent suppression," she had asked her

father to visit Sheridan and tell him not to expect a manuscript.

[31] She went on to say,

Mr. Sheridan was pleased to express great

concern, -- nay more, to protest he would not accept my refusal.

He begged my father to tell me that he could take no denial

to seeing what I had done -- that I could be no fair judge for

myself. [32]

Faced with Sheridan's insistence, Burney

says that her father "ever easy to be worked upon, began to waver,

and told me he wished I would show the play to Sheridan at once."

[33] Despite drawing up some lists of possible changes in case

Sheridan came knocking on the door demanding to see the script,

as he later threatened, Burney herself remained firm to the idea

of suppression, saying that she had "taken a sort of disgust to

it" and was "most earnestly desirous to let it die a quiet death."

[34]

Burney spent her last twenty years going

through her manuscripts, voluminous diaries and correspondence

and left behind only one manuscript of The Witlings (in

the Berg Collection). [35] Darby maintains that notes in the margins

of the manuscript include cuts to the text that were never made

and might have been in response to the criticisms around the satire.

[36] However, my own examination of the manuscript turned up no

conclusive evidence of marks indicating possible alterations to

eliminate offensive comedy. [37] The notations Darby refers to

are a series of X's in pencil that the librarian at the Berg Collection

says cannot be positively attributed to Burney (although there

is no record of annotations from any other source). [38] The notations,

which are only present in a short section of Act IV, mark passages

of dialogue that should be delivered as asides by the actor. The

section of Act IV that Darby regards as a major cut features bracketed

dialogue and a single X. This might be a cut of extraneous dialogue

at the beginning of Censor's entrance, but the X's do not indicate

cuts anywhere else in the manuscript-- they only mark asides (or

in one instance seem to be merely doodles). The marked section

is the only place where there is overlapping dialogue by more

than two people in the play, so the annotations may just have

been an attempt to call attention to the overlap which is not

indicated by stage directions. It is clear, in any case, that

the pages of Act IV are unevenly trimmed. The first two pages

are at least a quarter inch shorter than the rest of the act.

The majorityof the rest of the pages are curled at the edges,

suggesting they were all once part of the same folded folio (Acts

I and II are preserved, uncut, in similar folios). And this indicates

that there were very likely revisions made to the Act from the

original. But the purposes of the revisions aren't clear.

Burney would eventually write seven plays,

but see only one of them performed, Edwy and Elgiva (1795),

which was savaged by the critics, ending what might otherwise

have been a notable playwriting career. [39] Of her novel-writing

career, James E. Person Jr. says, "Burney is considered a significant

transitional figure who employed the methods of Samuel Richardson

and Henry Fielding to create a new subgenre that made possible

the domestic novels of Austen, Maria Edgeworth, and countless

other successors." [40] Given her impressive innovations in nondramatic

literature, Burney might well have become a leading dramatist

if she had been allowed room to grow as a dramatist.

Darby contends that in later life Burney

regretted the decision to suppress The Witlings. Notes

Burney made on her correspondence characterize her father's and

Crisp's critique as "severe" and called attention to the praise

the script received from other reviewers. [41] But the decision

undoubtedly promoted women's increased participation in the arts

and culture, or at least prevented serious setbacks and obstacles.

Perhaps most importantly, it preserved her reputation as a mentor

for the next generation of women writers. Jane Austen, a subscriber

to Burney's serialized fiction, was enormously influenced by Burney's

satires. [42] Pride and Prejudice owes its name and elements

of its plot to Burney's novel Cecilia, which was written

just after The Witlings and shares several of the play's

characters and storylines.

The line providing Austen with her title

may perhaps harken back to Burney's suppression of own play:

. . . remember: if to pride and prejudice

you owe your miseries, so wonderfully is good and evil balanced,

that to pride and prejudice you will also owe their termination.

[43]

--------------------------

NOTES

1. Frances Burney D'Arblay, Diary of

Frances Burney D'Arblay, p. 377.

2. Janet Todd,. The Sign of Angellica: Women, Writing and

Fiction, 1660-1800, p. 273.

3. Frances Burney, Journals and Letters, pp. xix-xxi.

4. Ibid., p. 98.

5. Ibid., p. 100.

6. Ibid., pp. xvi, 100.

7. Ibid., p. 111.

8. Ibid.

9. Deborah Heller,“Bluestockings and the Public Sphere,”

p. 59.

10. Ibid., p. 60.

11. Sue-Ellen Case. Feminism and Theatre, p. 46.

12. Burney, Journals and Letters, p. 101.

13. Ibid., p. 97.

14. “Elizabeth Montagu," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Montagu (accessed October

12, 2010)

15. Burney. Journals and Letters, p. 101.

16. Ibid.

17. Deborah Heller, "Bluestocking Salons and the Public Sphere,"

p. 62.

18. Ibid, p. 72. Quoted from D'Arblay, Diary of Frances Burney

D'Arblay, vol I, p. 364 (brackets Heller’s).

19. Ibid.

20. Elizabeth Robinson Montagu, 1720-1800, "Letter from Elizabeth

Robinson Montagu to Elizabeth Carter, June 06, 1758," p.

374.

21. Peter Sabor and Geoffrey Still, "Introduction" to

The Witlings, The Woman-Hater, p. xxxiii, note 19.

22. Barbara Darby. Frances Burney Dramatist, p. 24.

23. Elizabeth Child, “Elizabeth Montagu, Bluestocking Businesswoman,”

p. 154.

24. Ibid.

25. Case. Feminism and Theatre, p. 6.

26. Aristotle, Poetics, Else trans., Else attributes

this translation to Kassel in his note (105) to lines 54a24-6,

p. 99.

27. Frances Burney, The Witlings, p. 335

28. D'Arblay, Diary of Frances Burney D'Arblay, p. 263.

29. Ibid., p. 128.

30. Darby, Frances Burney Dramatist, pp. 24-25.

31. D"Arblay, Diary of Frances Burney D'Arblay,

p.436.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

35. Burney, Journals and Letters, pp. xxviii –

xxix.

36. Darby. Frances Burney, Dramatist, p. 25.

37. Fanny Burney, The Witlings, unpublished manuscript

in the Berg Collection, New York Public Library, examined October

8, 2010

38. A. Henry W. Thornton and Albert A. Berg Collection of English

and American Literature. Conversation with the author.

39. Darby,Frances Burney, Dramatist, p. 43.

40. James E. Person Jr., Burney, Fanny - Introduction. Nineteenth-Century

Literary Criticism. Vol. 54, p.1.

41. Darby. Frances Burney, Dramatist, p. 25.

42. John Wiltshire, “The inimitable Miss Larolles”:

Frances Burney and Jane Austen, p. 218.

43. Frances Burney. Cecilia, p. 930.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aristotle. Poetics, trans. Gerald

F. Else, Lansing, MI: Ann Arbor Paperbacks, The Michigan University

Press, 1970.

Burney, Frances. Journals and Letters, London: Penguin

Books, 2001.

Burney, Frances. Cecilia, Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 2008.

D'Arblay, Frances Burney, 1752-1840, Diary of Frances Burney

D'Arblay, September, 1778, in Diary and Letters of Madame

D'Arblay, vol. 1-6: 1752-1840. Barrett, Charlotte Frances,

ed. London, England: H. Colburn, 1842.

Case, Sue-Ellen. Feminism and Theatre, New York, NY:

Palgrave MacMillan, 1988.

Child, Elizabeth. “Elizabeth Montagu, Bluestocking Businesswoman,”

Huntington Library Quarterly Vol. 65, No. 1/2, Reconsidering

the Bluestockings, University of California Press (2002),

pp. 153-173.

Darby, Barbara. Frances Burney Dramatist, Lexington,

KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1997.

Heller, Deborah. “Bluestocking Salons and the Public Sphere,”

Eighteenth-Century Life, Volume 22, Number 2, May 1998,

pp. 59-82.

Johnson, Samuel. A Dictionary of the English Language,

London: Printed for A. Millar, 1766.

Montagu, Elizabeth Robinson, 1720-1800, "Letter from Elizabeth

Robinson Montagu to Elizabeth Carter, June 06, 1758," in

The Letters of Mrs. E. Montagu, With Some of the Letters of

Her Correspondence, vol. 4. London, England: T. Cadell &

W. Davies, 1809.

Person Jr., James E. Burney, Fanny - Introduction. Nineteenth-Century

Literature Criticism. Vol. 54. Gale Cengage, 1996. Accessed

electronically through the Gale Cengage database Jan 10, 2011.

Rogers, Katherine, ed., The Meridian Anthology of Restoration

and 18th Century Plays by Women, New York, NY: Penguin Group,

1994.

Sabor, Peter and Geoffrey Still, eds. The Witlings, The Woman-Hater,

London: Pickering & Chatto Limited, 1997.

Todd, Janet. The Sign of Angellica: Women, Writing and Fiction,

1660-1800. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

Wiltshire, John, “‘The inimitable Miss Larolles’:

Frances Burney and Jane Austen,” in A Celebration of

Frances Burney, Lorna J. Clark, ed., Newcastle, Cambridge

Scholars Publishing, 2007.