Psychic Bloodspurts

By Joseph Cermatori

Je suis sang

By Jan Fabre

Kasser Theater

Montclair State University

(closed)

Before The Poetics, the word "katharsis"

existed primarily as a medical term used to describe the processes

by which bodies rid themselves of waste matter: defecation, urination,

vomiting. The link to ancient Greek tragedy is hardly far-fetched,

however, since these processes would have played an important

role in the bacchanalian revels of the Great Dionysia festival,

which frequently involved excesses of feasting and intoxication.

Orgy, too, was a fundamental component of these festivals, and

perhaps ejaculation could also be considered a cathartic event.

The point is, before katharsis came to mean a mysterious

psycho-emotional release of pity and terror in the theater, it

had a more basic definition--the physical body actively discharging

its contents: the engorged feaster shitting, the drunken celebrant

vomiting or draining his bladder, the orgiast climaxing. Finally,

participants would have experienced a kind of vicarious catharsis

in the act of seeing the tragos's throat slashed and

its blood spilled outside its body. These were ecstatic rites;

that is, the experience of ekstasis--literally, to stand

outside, the feeling of transcending one's bodily limits, of the

self outside the body--was central. For the Greeks before The

Poetics, the phenomenon of catharsis was experienced as a

corpo-reality.

Jan Fabre knows all this intuitively. Over

the past twenty-five years, the work of this Flemish artist, in

theater and visual art, has been preoccupied with the body's physical

limits and its ecstatic potential for transgressing them. Some

of his early excursions into the visual arts famously used his

own blood for paint--a gesture that recalls Hermann Nitsch's bloody

Splatter Paintings, for which the paint is drained from

the corpses of animals that have been ritualistically slaughtered

in elaborate actions, or Marc Quinn's sculpture of his own head,

Self, which was made from more than a gallon of his congealed

blood. Other bodily fluids have received special attention as

well in Fabre's work. For instance, his Histoire des larmes

(Avignon Festival, 2005) focuses on the subject of tears and weeping.

Another recent project, Quando L'Uomo principale è un donna

(Paris, 2004; recently performed at Montclair State University)--a

choreographic hymn to Bacchus and to the mutability of sex--featured

a nude female dancer who rubbed olive oil and olives all over

herself before donning a crown of laurels, inserting the oily

olives into her vagina, pushing them out again, dropping them

into a martini, and then downing it, olives and all.

Similar concerns are apparent in Je

suis sang, a "medieval fairy tale" that Fabre and his company

Troubleyn created for the 2001 Avignon Festival. The piece was

revived at Avignon in 2003 and again in 2005 when Fabre acted

as Avignon's guest artistic director. In January 2007, it appeared

as part of MSU's Peak Performances series. The fluid at the heart

of this piece, as the title suggests, is blood. In it, Fabre meditates

on the psychic, physiological, and sociopolitical possibilities

of catharsis while eschewing the traditional Aristotelian ideology

of catharsis. Je suis sang, like much of Fabre's work,

surpasses the tragic altogether: according to Patrice Pavis (in

a piece on the 2005 Avignon Festival), its proper label is "calamity,"

tragedy in which Aristotelian catharsis is impossible, tragedy

fit for a contemporary world blighted by diseases without cure,

climate change beyond repair, conceptions of history bereft of

any logical utopian endpoint, modern crusades without end, and

international and sociopolitical collapse beyond all hope. What

might have been tragic is now as irresolvable and absurd as history.

Fabre rejects not only Aristotelian catharsis

in Je suis sang but also the familiar dramaturgical principles

derived from Greek tragedy that have dominated western theater

since the Renaissance. Instead, this piece takes its formal cues

from the medieval period (a recurrent motif in Fabre's work, seen

in Histoire des larmes, Tannhäuser [Brussels, 2004] and

elsewhere). He has said that his work is greatly influenced by

the Flemish painters of the middle ages, and the Bakhtinian and

infernal landscapes of Bosch are an unmistakable influence here.

Likewise, a great debt is owed to the iconographic and episodic

dramaturgy of station drama. Fabre thus recognizes a Flemish dramatic

heritage that extends as far back as the anonymous author of Elkerlijc,

or Everyman.

Je suis sang started out as a

poem inspired by the Cour d'Honneur of Avignon's Palais des Papes--where

it would ultimately premiere--and by the butchery of the medieval

Catholic Church. This poem forms the central textual element of

the piece. An English translation--the show is performed in French,

though Fabre and his company are from Dutch-speaking Antwerp--is

projected onto the blank upstage wall of MSU's Alexander Kasser

Theater. (The immense stone backdrop of the Cour d'Honneur, alas,

was absent from the performance in Montclair: in the Avignon productions

its fortress-like, Gothic majesty formed a crucial visual and

thematic element.) The first words, which don't appear until several

minutes into the action, become an unsparing refrain for the rest

of the evening: "It is 2007 after Jesus Christ. And we are still

living in the Middle Ages." For Fabre, the middle ages are synonymous

with an addiction to blood, and throughout the performance, his

text will insinuate and reinsinuate how this addiction remains

with us to this day.

The text, however, is in constant competition

with the visual spectacle, the importance of which cannot be understated.

True to Fabre's roots in painting, sketches, and the plastic arts,

this is a theater of images, albeit corporeal ones. When the audience

enters the auditorium, the event is already underway. Set against

the blackness of the upstage wall--which is empty and waiting

to be written upon--and amid a diffuse grey light, the action

takes place on a stage devoid of any set except for a number of

metallic tables, which wait in the exposed wings. Actors who look

like medieval smiths in chain-mail smocks work on and around them,

scrubbing at them with brushes, creating ambient noise. A chubby,

sweaty man, cherubic yet somehow sinister, with hair in platinum

ringlets, wearing only a red thong, dances suggestively around

the stage and puffs on a cigar whose smoke clouds the air and

assaults our nostrils. (Quando L'Uomo principale è un donna

has a similar opening, with a soloist lighting a cigarette.)

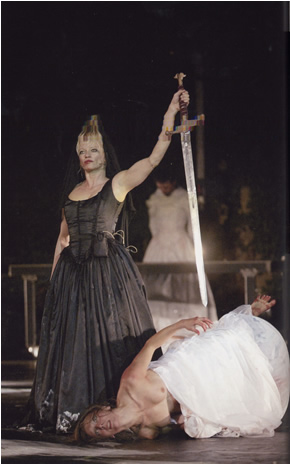

A woman in a long black gown (played by

Fabre's frequent collaborator Els Deceukelier) stalks about the

periphery of the stage carrying a book on her head and gazing

into the audience. A bearded knight in armor and black briefs

waits upstage center. A chorus of knights, also in armor and briefs,

marches out and performs a choreographed martial routine. Two

magisterial figures--one male and one female, both wearing long

green gowns and tin funnels on their heads, and both looking like

oversized chess pieces--enter from left and right to oversee the

onstage pageant. Neatly sewn into their gowns are short daggers.

As the dance concludes, the bearded knight steps out from among

them to begin a battle sequence with an invisible foe. Meanwhile,

the chess figures--the piece's récitants, it turns out--don

green medical smocks and latex gloves, as if preparing to perform

an autopsy before an audience of medical students. We have entered

the theatrum corpi.

The

Knight continues to battle his unseen enemy in what might be a

chivalric swordsmanship competition. (Games based on violence

recur several times throughout the piece in the form of knife

juggling, wrestling, and bull fighting, bringing to mind our civilization's

venerable history of bloodsports, which also includes gladiatorial

competition, bearbaiting, and so forth.) As the battle continues,

the Knight begins to fall repeatedly and with mounting violence.

At the climax, a jet of blood sprays from his mouth.

The

Knight continues to battle his unseen enemy in what might be a

chivalric swordsmanship competition. (Games based on violence

recur several times throughout the piece in the form of knife

juggling, wrestling, and bull fighting, bringing to mind our civilization's

venerable history of bloodsports, which also includes gladiatorial

competition, bearbaiting, and so forth.) As the battle continues,

the Knight begins to fall repeatedly and with mounting violence.

At the climax, a jet of blood sprays from his mouth.

What transpires over the next ninety minutes

amounts to a continual psychic bloodspurt, an Artaudian deluge

of images, ideas, and sensory attacks, arranged in a theatrical

form that resembles the interweaving structures of medieval polyphony.

Before our eyes and ears: a woman clad only in white panties sings

"Son of a Preacher-Man" (in Quando L'Uomo . . . it's

"Volare" that we hear); screeching heavy metal music blares from

a rock band that includes several electric guitars and an amplified

tuba; brides in wedding dresses bleed from their crotches while

a chorus of men emasculate one another, the castrations represented

by bloody socks over their penises; women pantomime using blood

as rouge and lipstick; actors form human cadavres exquis;

acts of bloodsucking (from women's nipples and other body parts)

and bloodletting transpire, as does Chinese medicinal fire cupping

(to stimulate the circulation, for sexual pleasure, or both?);

actors adopt the sadomasochistic iconography of Saint Sebastian

while the spoken poem muses on the lifegiving (i.e. eucharistic

and vampiristic) qualities of drinking blood; mimed tortures and

mutilations take place that bring to mind not only the Inquisition

but also Titus Andronicus and the Holocaust. In short,

Je suis sang is pure carnival, and fittingly so, since

the performance strives to bid farewell to the flesh, to let blood

transgress the bounds of the body and flow freely, transcendentally,

in absolute catharsis.

Fabre represents this transcendence near

the end of the piece, in a moment when the two récitants

rhythmically incant a litany of more then thirty self-inflicted

incisions. This is not a reference to neurotic self-injurious

behavior; the poetic cuts are obviously meant to be mortal wounds:

slashes to the throat, to the arms and legs, to the genitalia.

With

each cut, they describe the opening of a different major vein

or artery, and the woman in black chants the blood vessels' scientific

Latin names in antiphonal response. As vein after vein is verbally

opened, driving home images of blood gushing forth in floods,

the poetic rhythm grows hypnotic, sublime, and strangely hopeful.

The only way to escape the absurd, never-ending calamity of existence,

it seems, is to transform the landscape of the body into a gushing

flood. "In life, two things are certain, and they may actually

be the same," the chorus bellows at us, in English, "we shall

die, and we shall exceed limits."

With

each cut, they describe the opening of a different major vein

or artery, and the woman in black chants the blood vessels' scientific

Latin names in antiphonal response. As vein after vein is verbally

opened, driving home images of blood gushing forth in floods,

the poetic rhythm grows hypnotic, sublime, and strangely hopeful.

The only way to escape the absurd, never-ending calamity of existence,

it seems, is to transform the landscape of the body into a gushing

flood. "In life, two things are certain, and they may actually

be the same," the chorus bellows at us, in English, "we shall

die, and we shall exceed limits."

Je suis sang culminates the only

way a post-cathartic tragedy can--in pure apocalypse and Dionysian

bedlam. The stage is transformed into something like a live version

of Bosch's Hell: amid screaming, goldfish swallowing,

and the deafening wail of electric guitars and explosive tuba

belches, ensemble members don enormous ears (rabbit ears? jackass

ears?) and torture blindfolded brides demonically. White powder--the

dust of civilization?--flies everywhere. The chorus strips nude

and douses itself in Chianti. The satyr-like cherub appears naked,

tarred and feathered. In short, the spectacle confronts its audience

with a vision of complete dystopia, Wagnerian in its overwhelming

totality. The tables are lined up across the stage and tilted

on their sides to form a tall, monolithic wall, not unlike those

of the Cour d'Honneur. The chaos falls silent. Blood oozes out

from behind the wall of tables, finally released and uninhibited,

in a profusion that is every bit as sacred, as spontaneous, and

as disturbing as the stigmata.

This is one of only two moments in the

entire performance when we see liquid blood onstage; the blood

that comes from the Knight's mouth near the beginning is the other.

In both cases, we assume that what we see is mere stage blood,

and that there is never a moment of actual bloodshed. It is interesting,

given Fabre's obsession with the existential realness of the human

body onstage, that he opts for this relative dryness. Perhaps

his greatest accomplishment with Je suis sang is a kind

of reassociation of sensibility: he needs only to invoke the idea

of blood through his hallucinatory poetics and theatrics, and

the sheer thought of it is enough to awaken the experience of

its actual physical presence within us.