The

Poison Talking

The

Poison Talking

By Una Chaudhuri

Long Day's Journey Into Night

By Eugene O'Neill

Plymouth Theater

236 W. 45th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

They're back. And they're at it again.

America's First Family, the everlasting Tyrones, back in their

summer cottage on the beach, back to face the grim music of their

disappointments and despair, and back also to challenge us to

account for ourselves, our hopes and dreams, our betrayals and

breakdowns. In the masterful revival of Long Day's Journey

Into Night at the Plymouth Theatre, the appalling difficulty

of the play yields a rare theatrical experience, four hours of

self-disclosure of an intensity that renders the distinction between

actor and character altogether academic. Under Robert Falls's

sure direction, Vanessa Redgrave, Brian Dennehy, Phillip Seymour

Hoffman, Robert Sean Leonard and Fiana Toibin, give performances

of historic caliber and consequence, laying bare a new layer of

this play's endless insights into the American cultural imaginary.

As the country embarks on a possibly disastrous political journey,

this mother of all American plays speaks of the limits--even the

pathology--of self-involvement.

The main insight of O'Neill's play is the

idea that hell is not just--as Sartre famously had it--"other

people": it is other people to whom one is tied with bonds of

blood and biography. Hell is family. Hell is that welter of indestructible

memories and stone-etched resentments, the ceaselessly repeated

exchanges of anger, sorrow, need, disappointment, frustration,

and shame that is the dark language of kinship. "Written in blood,"

as O'Neill himself described it, Long Day's Journey Into Night

was also written in that first, horror-stricken understanding,

given by psychoanalysis, of the explosive tensions and crippling

toxicity of what later came to be called, without irony, the nuclear

family. With its unflinching ear for the cruel insinuations and

shocking outbursts of family talk, Long Day's Journey

towers above such later classics of the genre as Pinter's The

Homecoming and Shepard's Buried Child by virtue

of its painful and patently autobiographical honesty. This day

in the life of an aging couple and their two sons lays bare the

author's own struggle to wrest creativity from family pathology,

art from illness, truth from failure.

The power of the play, it has often been

said, is largely due to its intense inward focus: although the

text states that the action occurs in 1912, the play does nothing

to bring that action into relation with any public events of those

tumultuous times, nor of those (including a world war) in which

the play was written, 1939-40. The Tyrones seem a world unto themselves,

hermetically sealed off from everything else.

And yet a keen awareness of the larger

world was one reason O'Neill gave for imposing the notorious twenty-five-year

posthumous ban on publication of the of the play (and unlimited

ban on production): while often remarking that this was the finest

thing he had ever written, he added that it was not a work he

wanted to bring to the world "in this crisis-preoccupied time."

His wife and executor, Carlotta, did not honor these requests.

The play was published three years after O'Neill's death and premiered

the same year, 1956, in Stockholm, Sweden. The young director

of that production, Bengt Ekerot, regarded the play as the definitive

accomplishment of the Ibsenite-Chekhovian paradigm of psychological

realism, in which everything emanated from impulses deep within

the characters, nothing from the world around them. By contrast,

the first--and now legendary--American production, directed by

Jose Quintero, set the emotional mass of the family's interactions

within a larger framework suggested by the play's diurnal structure

as well as its major symbolic image: the fog. Quintero asked for

a design that would "bring nature into the set" and show the characters'

journey in relation to "the various speeds and moves that the

sun experiences as it makes its long voyage across the sky." David

Hays, the designer, responded with a set built around three large

windows, through which the play's powerful non-human actors--the

sun, sea, and fog--entered to shape the family drama into a tragedy

of radical non-belonging.

In the half-century since those premieres,

the play has become a monument of both psychological realism and

poetic symbolism. The forms of behavior and rhythms of speech

that constitute the family's pathology have been brilliantly observed

to the point of clinical diagnosis. At the same time, the halting

lyricism of the young poet's self-accounting--"stammering is the

native eloquence of us fog people," says the character Edmund--is

matched by a paradoxical landscape of open sea and enclosing fog,

the romance of the one contrasting bitterly with the carceral

effects of the other. In the acclaimed 1988 Stockholm production

directed by Ingmar Bergman (which visited BAM in 1991), the impact

of environment on the inner life of the characters was literalized

through the expressionist device of still images projected behind

the stage: the facade of the house, a closed door, the fog enshrouded

house, at the end a radiant tree. Bergman also disrupted O'Neill's

insistent unity of place by setting the last act on the verandah

of the cottage, placing Edmund closer to the outside world. Few

productions have pushed the play toward a more specific social

context, although European ones have frequently looked for the

characters' universal humanity through an understanding

of their American context. The director of the first Italian production

(Milan, 1956) asked if "anyone who looks closely at Edmund and

James" would not be reminded of "the two sons of Willy Loman,

Miller's traveling salesman? Their fall/failure takes place on

the same terrain."

Willy

Loman might easily come to mind in the widely acclaimed production

currently on Broadway, if only because Death of a Salesman

was the last, and hugely successful, collaboration between the

play's director Robert Falls and one of its stars, Brian Dennehy.

Dennehy indeed brings a kind of white-collar pathos to the role

of James Tyrone, highlighting the money-anxieties of the potato-famine

Irish immigrant over the bluster of the bardolatrous actor. His

petty self-delusions are no match for his wife's titanic regrets,

which inexorably drag the men around her into the depths of despair.

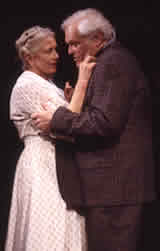

As played by Vanessa Redgrave, Mary Tyrone dominates this excavation

of O'Neill's subterranean labyrinth of regret and recrimination.

Her performance is so detailed and so riveting that it changes

the basic question of the play, the one rooted in its retrogressive

action: why is she so hurt, angry, damaged? Watching Redgrave

go from flirtatious playfulness to sadistic sarcasm to terrifying

attack and finally back to childlike innocence, one finds her

husband's explanation--"it's the poison talking"--utterly unsatisfying.

Watching her flutter and start and fidget and--in one heartbreaking

moment--literally climb the walls, one wonders: what is the poison

really saying?

Willy

Loman might easily come to mind in the widely acclaimed production

currently on Broadway, if only because Death of a Salesman

was the last, and hugely successful, collaboration between the

play's director Robert Falls and one of its stars, Brian Dennehy.

Dennehy indeed brings a kind of white-collar pathos to the role

of James Tyrone, highlighting the money-anxieties of the potato-famine

Irish immigrant over the bluster of the bardolatrous actor. His

petty self-delusions are no match for his wife's titanic regrets,

which inexorably drag the men around her into the depths of despair.

As played by Vanessa Redgrave, Mary Tyrone dominates this excavation

of O'Neill's subterranean labyrinth of regret and recrimination.

Her performance is so detailed and so riveting that it changes

the basic question of the play, the one rooted in its retrogressive

action: why is she so hurt, angry, damaged? Watching Redgrave

go from flirtatious playfulness to sadistic sarcasm to terrifying

attack and finally back to childlike innocence, one finds her

husband's explanation--"it's the poison talking"--utterly unsatisfying.

Watching her flutter and start and fidget and--in one heartbreaking

moment--literally climb the walls, one wonders: what is the poison

really saying?

What is this masterpiece of American drama

saying at this "crisis-preoccupied time," so different

from the one in which it was conceived? Are those elusive forms--modern

tragedy, American tragedy--more possible in the aftermath

of our recent horrors, and can O'Neill's family saga be a resonant

echo chamber for the nation's sorrow? The set of this production,

designed by Santo Loquasto, suggests something of the trajectory

the meanings must now follow. The set tells a story of radical

otherness, framing the anguished subjectivity of the

characters within an immense and eloquent objectivity. The stage

is dominated by a vast expanse of dark wood, the walls of the

Tyrone family house stretching endlessly upward. The naturalistic

living room, neither cozy nor cold, neither shabby nor elegant,

lies low to the ground, weighed down by the mass of darkness rising

above it. As they tower above the anguished action of the play,

these mammoth walls signify ceaselessly: they are the walls of

a tomb, the hull of a ghost ship, the trunk of a gigantic tree.

Over time (and of course it is a long, long time, over

four hours) they become the overarching and inflexible contours

of the human condition, simultaneously amplifying and dwarfing

the anguish of the frail creatures beneath them. Under their impassivity,

the Tyrones's self-analysis, pathologically rigorous as it is,

is revealed as inadequate to the complex challenge of living maturely

in the real world.

Edmund laments that he was born a man:

"I would have been more successful as a sea gull or a fish." Invoking

the non-human world of mute creatures and silent things, the poet

longs for an alternative to the destructive "talking" of the poisoned

self. Although this production eschews a transcendence of the

kind signified by Berman's radiant tree, its courageous pursuit

of everything that lies beneath the "talking" brings another kind

of resolution into view: the exhaustion of inwardness and the

turn to the outside world, with hope and humility.