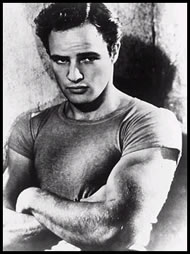

Player's Dispassion: The

Style of Marlon Brando

By Robert Brustein

The death of Marlon Brando at the age of

eighty signifies the end not only of a great screen icon, but

of an entire era of American realism. Brando famously broke upon

the American consciousness playing Stanley Kowalski in the Broadway

production of A Streetcar Named Desire in 1947. It was

a stunning demonstration of naturalistic acting that left an indelible

mark on everyone who saw it. In a role Tennessee Williams designed

as a brute beast slouching towards Bethlehem, Brando leavened

his character's violent outbursts with a glowering sensitivity

that tipped the sympathies of the audience away from Blanche towards

Stanley (when Anthony Quinn replaced him in the role, we saw a

lesser performance but one more faithful to the author's vision

of a selfish lout swatting a helpless moth).

Stanley Kowalski was not Brando's first

part on stage, but it was to be his last. Hollywood beckoned,

first with The Men, a film about paraplegics, then with

the screen version of Streetcar, then with Viva Zapata!,

and soon with On The Waterfront for which he won his

first Oscar in 1954. Eighteen years later, he rejected his second

Oscar, for his groundbreaking performance in The Godfather,

through the agency of a Native American woman who took the occasion

to read his statement protesting Hollywood's treatment of American

Indians.

By

this time, Brando had become both the Peck's Bad Boy of Hollywood

and the Maserati Radical of Beverly Hills, lending his name to

causes as far afield as Martin Luther King’s civil rights movement

and the Black Panther Party. Although he earlier had supported

Israel and denounced the plight of Soviet Jewry, he later raised

some hackles by saying that Hollywood was controlled by greedy

Jews who failed to show enough social conscience. Meanwhile, he

was extorting huge sums from these moguls for every movie he made.

He married three times and had innumerable mistresses, mostly

non-Caucasians, though his Indian wife (Anna Kashfi) embarrassed

him by turning out to be Irish. He named some of his eleven children

after Native American tribes or after his movie parts, and suffered

the pain of seeing one of them (his son Christian) get convicted

for murder, and another (his daughter Cheyenne) die a suicide.

By

this time, Brando had become both the Peck's Bad Boy of Hollywood

and the Maserati Radical of Beverly Hills, lending his name to

causes as far afield as Martin Luther King’s civil rights movement

and the Black Panther Party. Although he earlier had supported

Israel and denounced the plight of Soviet Jewry, he later raised

some hackles by saying that Hollywood was controlled by greedy

Jews who failed to show enough social conscience. Meanwhile, he

was extorting huge sums from these moguls for every movie he made.

He married three times and had innumerable mistresses, mostly

non-Caucasians, though his Indian wife (Anna Kashfi) embarrassed

him by turning out to be Irish. He named some of his eleven children

after Native American tribes or after his movie parts, and suffered

the pain of seeing one of them (his son Christian) get convicted

for murder, and another (his daughter Cheyenne) die a suicide.

Physically, he had transformed from the

graceful loping Terry Malloy of Waterfront into the elephantine

hulking Kurtz of Apocalypse Now, ballooning into a figure

so huge that he could only be photographed in shadows. Like Marilyn

Monroe, he became notorious for his delinquent artistic behavior--cutting

up on the set, showing up late, and failing to learn his lines

(much of his deliberate pacing with certain characters was a result

of his reading his cues off idiot cards). The great actress and

teacher, Uta Hagen, once wrote a book called Respect For Acting.

Brando's autobiography, Songs My Mother Taught Me, would

have been more accurately called Contempt for Acting.

F. Scott Fitzgerald regretted that he had

been "a poor caretaker of my talents." Brando was a really slobbish

janitor of his own. He never recognized that his mighty acting

gift was his only by sufferance. He was, by nature, a lazy man

who preferred hanging out on beaches in Tahiti to developing his

craft and sullen art ("The only reason I'm here," The New

York Times quotes him as saying, "is that I don't yet have

the moral courage to turn down the money"). Surely that same laziness

was responsible for what I consider Brando's greatest artistic

delinquency, his failure ever to return to the stage.

Being

in a position to pick any role he wanted, he could have single-handedly

revolutionized the American theatre. Alas, Brando's mutinies remained

confined to the Bounty. Actors were following Brando's example

not only by imitating his partly deliberate, half-improvised vocal

mannerisms (you can see his influence on Paul Newman, Steve McQueen,

Jack Nicholson, Robert DeNiro, James Dean, Ben Gazzara, and a

host of others). They also imitated him by neglecting a crucial

obligation of the actor, which is to preserve the great roles

of the classical and modern repertory. (Brando did attempt to

play Marc Antony once in John Houseman's movie version of Julius

Caesar about which John Gielgud, playing Cassius, wrote loftily:

"Marlon looks as if he is searching for a baseball bat to beat

his brains with.") I do not mean to underestimate Brando's genuine

achievements as a movie actor, or those of his gifted imitators.

His Vito Corleone may be the single greatest performance ever

filmed. But Brando did not have a sufficient sense of the actor's

calling to help advance the cause of theatrical art, which may

be why he became embroiled in so many causes he knew little about.

Being

in a position to pick any role he wanted, he could have single-handedly

revolutionized the American theatre. Alas, Brando's mutinies remained

confined to the Bounty. Actors were following Brando's example

not only by imitating his partly deliberate, half-improvised vocal

mannerisms (you can see his influence on Paul Newman, Steve McQueen,

Jack Nicholson, Robert DeNiro, James Dean, Ben Gazzara, and a

host of others). They also imitated him by neglecting a crucial

obligation of the actor, which is to preserve the great roles

of the classical and modern repertory. (Brando did attempt to

play Marc Antony once in John Houseman's movie version of Julius

Caesar about which John Gielgud, playing Cassius, wrote loftily:

"Marlon looks as if he is searching for a baseball bat to beat

his brains with.") I do not mean to underestimate Brando's genuine

achievements as a movie actor, or those of his gifted imitators.

His Vito Corleone may be the single greatest performance ever

filmed. But Brando did not have a sufficient sense of the actor's

calling to help advance the cause of theatrical art, which may

be why he became embroiled in so many causes he knew little about.

Perhaps he was trying to compensate for

his non-verbal style of acting. Brando virtually invented a type

that many years ago I called "the inarticulate hero in American

life." Whereas, in the 1930s, American dramatic characters--typically

those of Odets and Barry and S.N. Behrman--were essentially talkers,

by the late '40s the mumbling, steaming, explosive figure Brando

first created as Stanley Kowalski had become the archetypal American

dramatic hero (O'Neill's Hairy Ape was the prototype). Unlike,

say, Ralphie Berger in  Awake

and Sing, who was able to find a political voice with which

to air his grievances, the new hero was less inclined to describe

an injustice than to stomp on it. That these characters sometimes

had a gentle side to their nature made them no less threatening.

Like Melville's stammering Billy Budd, who could respond to slander

only by killing his defamer, the inarticulate hero was always

primed to erupt into violence.

Awake

and Sing, who was able to find a political voice with which

to air his grievances, the new hero was less inclined to describe

an injustice than to stomp on it. That these characters sometimes

had a gentle side to their nature made them no less threatening.

Like Melville's stammering Billy Budd, who could respond to slander

only by killing his defamer, the inarticulate hero was always

primed to erupt into violence.

But for all his artistic and moral failings,

regardless of his behavior on and off the set, there is no question

that Brando was an acting genius. His contribution is often described

as having brought American naturalism to its ultimate conclusion.

But looking at any of Brando's performances now, it is possible

to see how highly stylized they are. Take his Stanley Kowalski,

which, at the time, seemed so spontaneous and intuitive one thought

he was making it up as he went along (Brando did, indeed, improvise

a lot of his own lines but not those). His approach to that character

now seems almost as mannered to the present generation as, say,

Barrymore's snorting Hamlet did to the generation of the '40s.

Every age believes it has reached the ultimate truth in acting

when it has only achieved the ultimate in its own style. It is

a shame that this great actor only applied his extraordinary style

to a limited number of contemporary movie roles, brilliant as

some of them were. Inside that huge prodigal body was imprisoned

a supreme artist too seldom permitted to serve the actor’s calling.