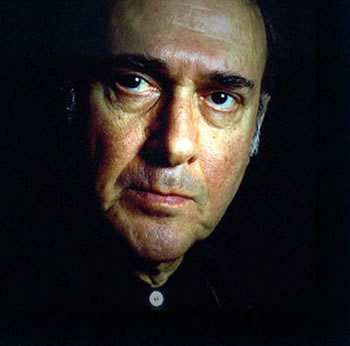

Our Caretaker

By Lydia Stryk

I almost met Harold Pinter several years

ago. An actor I was visiting in the National Theatre canteen was

on rehearsal break from a Pinter play which Pinter was directing.

I could easily have asked to meet the man. I longed to meet him.

No doubt, because he was a kind man, he would not have refused

a worshipful playwright a moment of his time, however American

she may have been.

But what would I have said? The scenario,

as I imagine it--had I asked and received that moment with Pinter--goes

like this: I enter the room, he turns to face me. My eyes grow

large, and rejecting his outstretched hand, I fall on to his breast,

sink down onto my knees in an act of penance, and begin to sob--burning

convulsive sobs without end.

There were no words, and they are no easier

to come by today, knowing he is gone forever.

It's funny to discover, in tribute after

tribute, that a large number of those who love Pinter love The

Caretaker best. Turns out, we're all alike. But then, it's

no surprise. Not only is it the greatest contemporary metaphorical

play--that smashed Buddha--but it also contains one of the great

comic roles of all times in the homeless tramp, Davies. If you

saw Michael Gambon in the role you died and went to heaven that

night like I did.

This beloved play that asks (among boundless

questions) just what we expect from those upon whom we extend

our compassion, just who we think we are to insist on gratitude

in this bloody unjust world, also prefigures the sad reality that

nothing Pinter did for the theater world has been paid back with

thanks. I don't mean the thanks of fame and honors. He had those

aplenty. But the reward of our learning and heeding. He took care

that the theater should be a place of metaphor. He took care of

the poetry. He took care of the discomfort. And mostly he presided

over the mystery--understanding that what is mysterious is meaning

and that nothing less than meaning belonged in the theater.

Without these things, the theater, like

the setting of that fierce play of his, will be left a vacant

building filled with junk.

And in this way and many others, but in

this way most tragically, his watchful presence is irreplaceable.

------------------------

Ed. Note: A version of this article

originally appeared in The Brooklyn

Rail.