Modern Geek Theater

By Paul David Young

The Jester of Tonga

By Joseph Silovsky

P.S. 122

(closed)

If there is subgenre called "geek theater"

it's what Joe Silovsky is doing in his one-man, one-robot show

The Jester of Tonga, which recently concluded a short

run at P.S. 122. And I mean this in a kindly way.

In Silovsky's stage presence, the technology

of the production, and content, The Jester of Tonga is

thoroughly and charmingly geeky. It reminds me a lot of the sweet

inventions that my grandfather was always coming up with to entertain

us children: constantly changing dioramas hidden behind an oil

painting, a haunted house built into his attic, an elaborate miniature

circus for which he had carved all the animals.

The difficulty with Silovsky's particular

application of the geek aesthetic is that it ends up being an

arid and forgettable enterprise. He steadfastly refuses to own

up to a personal connection to the material, other than the rather

neutral fact, which he finally mentions halfway through the show,

that on his birthday in 2001 he happened to find an article in

The New York Times describing how the king of Tonga had

lost millions of dollars on exotic investments in the United States.

Would it be too much to ask why Silovsky was intrigued by this

material? The connection must have been strong for him to have

pursued the project for seven years, but he never tells us anything

about this.

I understand and am sympathetic to Silovsky's

strategy of eliciting myriad narrative strains from his apparently

random find. He does create an interesting, though confusing space

in which to think during his show. During the first half, unless

we read the press release, we don't know why he's telling us any

of these stories or doing a flyby review of the mathematics of

viatical valuations. In the second half, after he belatedly discloses

the Tongan news article, we can begin to construct a mental diagram

of the crisscrossing paths. Some of these relate to Silovsky's

pursuit of stories and people at considerable remove from the

Tongan financial disaster. Others are byproducts of his performance

archeology, people and random facts that turned up over the years

of his research. He could, however, have created a vastly more

interesting and layered experience had he been more careful about

his digging -- preserving the images of the objects uncovered,

illuminating their provenance, and probing further at every turn.

I'm not asking for easy answers, or even any answers, but rather

greater respect for his delightful discoveries and for the geeks

in his audience who want to know more about him and the Jester.

That's why we came to the theater in the first place.

Silovsky's self-defeating caution finds

its metaphor when he hides behind a screen for the opening sequence.

Attached to the screen is a hand-painted sign with the title "Jester

of Tonga." Silovsky settles in at a microphone and tells us it's

going to be a long journey, by which he's referring to many things:

the travel time between New York and Tonga, the seven-year duration

of the project, and the layers of information and story that will

occupy the evening. Oddly, despite his reported obsession, Silovsky

seems ambivalent about the task of performing; he holds back,

neither showing enough of his amiably awkward self nor plunging

full-on into his material.

As he narrates the opening sequence in

his mellifluous voice, he operates deliberately crude miniatures

in a contraption that works as a kind of projecting light box.

During the first journey, a model plane on a visible wire flies

in front of painted clouds. Silovsky is not interested in stage

illusionism, except to provide a good laugh. The stage is stripped

to the walls and loaded with things, each of which will play some

role in what is to come. The undisguised operation of these contraptions

is the great geeky pleasure of his show.

He's soon telling us one of many stories

about outsiders venturing into the Pacific. In this first one,

a cut-out boat runs aground on a Pacific atoll. Paper lightning

bolts dart in from the "sky," visibly manipulated by Silovsky.

He produces oral sound effects as well as the voice-over narration.

In this ghastly story, shipwrecked voyagers consider eating a

dead crew member, since they've little other food. When they valiantly

choose to send him off to a sea burial instead, the deceased is

represented by a series of smaller and smaller effigies that appear

in succession as his body floats away.

Silovsky then happily tells us that this

story is irrelevant to the main subject of the evening. During

the short set-up break that follows, we see him scurrying around

the stage, dressed in full geekwear: a "Larry's Steakhouse" t-shirt

and jeans and clever eyeglasses. In what seems at the time to

be another irrelevance, he gives a short lecture on viaticals,

a commercial exchange in which the owner of a life insurance policy

sells the benefits to someone else, in effect placing a bet on

when he will die. The seller is typically someone who has been

diagnosed with a fatal disease and wants to cash out on the policy.

An Arizona company called Millennium Art Management packaged viaticals

into securities that it marketed as a mutual fund, Silovsky explains.

Silovsky is endearingly awkward here, seeming to apologize for

the fact that he actually understands the mathematics of how viaticals

are valued and securitized.

But we hardly have time to puzzle over

the purpose of this lecture before he launches into his next sequence,

about the arrival of the man who will become the Jester of Tonga.

The arrival is staged inside a suitcase, which opens to reveal

a pop-up diorama of the main island of Tonga, a South Pacific

archipelago. Cameras inside the case provide live video feed to

monitors distributed throughout the theater. A cut-out boat dances

up to the island. Small figures of islanders wait by the shore.

Silovsky pushes a button and the king's palace pops up. He describes

the special gifts the visitor brings to please the king's peculiar

tastes: a clock (the king is obsessed with time) and a statue

of a cowboy (replica of a much larger one that is visible from

an interstate highway in the American West, we're told in another

digression). Some background information on Tonga is offered,

using a large sheet of paper to show what a small island it is

in the middle of the vast Pacific.

Only at this point does Silovsky finally

provide a clue to his fascination with Tonga, belatedly mentioning

the Times article which reported that, under the guidance

of someone variously known as Dean Jesse or the Jester of Tonga,

the Tongan government lost several million dollars by investing

in viaticals.

To

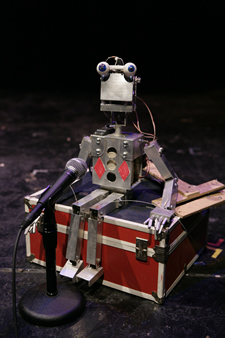

play the part of the Jester, Silovsky introduces Stanley, a robot

of his own creation, with limited mobility and functionality.

The Jester's recorded voice speaks through Stanley, who moves

his arms and head in a rudimentary facsimile of human behavior,

while Silovsky performs live beside him. This technique of pairing

a live performer with a recorded presence is a staple of The Builders

Association, a group for which Silovsky works. Because of Stanley's

technological limitations, however, he shares many of the same

problems as Silovsky on stage. Like Silovsky, Stanley is only

haltingly present.

To

play the part of the Jester, Silovsky introduces Stanley, a robot

of his own creation, with limited mobility and functionality.

The Jester's recorded voice speaks through Stanley, who moves

his arms and head in a rudimentary facsimile of human behavior,

while Silovsky performs live beside him. This technique of pairing

a live performer with a recorded presence is a staple of The Builders

Association, a group for which Silovsky works. Because of Stanley's

technological limitations, however, he shares many of the same

problems as Silovsky on stage. Like Silovsky, Stanley is only

haltingly present.

The Jester's life story is an absurd vortex

of alternative California lifestyles from the 1960s onward. Jesse

gets stoned for ten years straight until he discovers Kundalini

yoga, which unleashes in him the capacity to read minds and costs

him two sleepless weeks. The insomnia ends when he happens upon

a roomful of chanting Buddhists, which somehow leads him to a

job in a local bank despite the fact that he knows nothing about

financial services. At the bank he chances upon the Tongan account.

Jesse becomes the Tongan king's best friend, receives the title

"Jester for Life," and serves as the king's financial advisor,

at first preventing financial losses in stock investments but

then losing millions in risky viaticals. This is potentially fantastic

material, but Silovsky lets it fizzle out.

Before we can care about the Jester's life,

Silovsky is off on another digression, telling (with pop-up figures

in another suitcase) how he befriended a local Tongan seaman who

took him out dynamite-fishing and brought him to the island used

as Tonga's prison. Silovsky wants to supply a prisoner with reading

material but the only thing Silovsky's brought with him is a periodical

called Nuts and Volts. Later he sends a pulp novel whose

plot Silovsky dutifully summarizes. We hear of rioting and violence

against Tonga's Chinese immigrants and see a video of Silovsky

finally meeting the Jester in a New York diner. Then it's abruptly

over.

I coincidentally saw Mike Daisey's solo

show If You See Something Say Something at Joe's Pub

the same week I saw The Jester of Tonga. The structure

of Daisey's show is like Silovsky's: a weird personal obsession

that spawns research and field trips and strange encounters with

oddball people. Admittedly, Daisey has an entirely different stage

persona. He is an old-school actor, very comfortable on the stage,

despite his obesity and incessant perspiration. Daisey is willing

to bellow and roar and he does without any technology or even

movement. He doesn't need it because he has crafted fine material

by asking himself the difficult questions that will make a room

go quiet.

That's just what Silovsky doesn't do: push

his stories until they say something or raise disturbing questions,

tie them to something about himself and hard issues in the world,

so we can understand why he was so attracted to them to begin

with. Silovsky gives us a lot of fun stage puppetry but not enough

hardy story-telling. Forgoing his personal story, Silovsky uses

other people's voices but doesn't let them tell their stories

much either. Unlike Daisey, he doesn't draw them out to investigate

the concrete facts that accumulate and gather force.

Silovsky's geeky, withholding stage presence

alone, operating his fun mechanical and electronic inventions,

has to carry the performance. I have no doubt that he is capable

of forging a more compelling performance. He is obviously intelligent

and genuinely geeky. He needs to open up and talk to us.