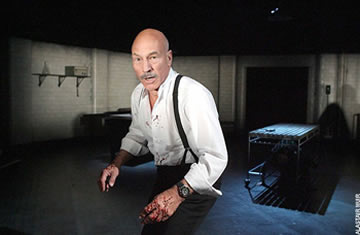

Macbeth's Young Frankenstein Moment

By Adam Casdin

Macbeth

By William Shakespeare

Lyceum Theatre

149 W. 45th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

What's really disturbing about Macbeth,

August: Osage County, and Young Frankenstein

is, surprisingly, that they are amped-up and over-stimulating

in similar ways: broad humor and unpredictable flashes of blinding

strobe light (Young Frankenstein); cartoonish emotional

cruelty (August, where it's not enough to have one sister

in love with her first cousin, he also has to be her half-brother);

and a shock-and-awe (sound and fury?) staging (Macbeth)

where actors are pitted against the light and audio effects.

I have my own version of Macbeth

in my mind, a sense of how it should be played, and maybe that's

part of my problem with the current production. But really, that

opening scene where the soldier on the gurney writhes and screams

his dense, metaphorical battle narrative is the problem. Could

anyone understand his words? I don't think so. Instead, we get

what information we need visually. It no longer matters that through

this narrative Shakespeare presents us with a type of storytelling--heroic,

epic even--that he uses as a counterpoint to his tale's origin

in our own dark desires.

My impression is that director Rupert Goold

believed audiences wouldn't understand half of what was being

said--maybe he's right?--and therefore gave them the emotional

tenor of the characters through a broad delivery assisted by audio-visual

prompts. And that's the problem: Young Frankenstein-August-Macbeth

converge in a theater where ambiguity is out and amplification

is in. Why leave us scratching our heads, wondering what in the

world just happened, when you can sit back and watch familiar

feelings fly. I may not expect Young Frankenstein to

make me question my reality, but a joke can surprise me into seeing

the world from a different perspective. I'll suspend my disbelief

and say that Mel Brooks can even do this with a penis joke. That

Young Frankenstein is humorless is probably not a surprise.

That there's no ambiguity in this production of Macbeth

is a tragedy. Lady Macbeth comes on so strong in our first meeting

with her that she's hardly human, or inhuman. She's a stock character

here, mostly. And Macduff, a troubling figure in the play, doesn't

worry us much. He comes round in the end and saves the day.

And, sticking with the play's opening,

how can you not have the witches, Shakespeare's frame for all

that follows, open the play? Juxtaposed against their supernatural

vision, the Macbeths' unnatural worldview, calculatingly human,

emerges. In this staging, the witches remain onstage nearly the

entire show, malevolent ghouls orchestrating the mayhem. And yet,

in some sense, Shakespeare casts his witches as strangely, weirdly

sympathetic--kicking against their mistreatment at the hands of

the world's rump-fed runions--ambitious for power no less than

Macbeth and Lady Macbeth. Real evil arrives only in mock form:

Malcolm's pretended "avariciousness" is there at the play's end,

not only as a test for Macduff, not only to suggest that everyone

is manipulating everyone else, but to give us a view of a truly

horrifying articulation of the dark prospect that human ambition,

not directed to an appropriate object, as Bill Clinton once put

it, opens before us. Against that example, Macbeth's descent into

the inhuman is a profoundly human, almost understandable problem.

A set of ideas came together in my mind

as I was trying to articulate my frustration with the performance.

I'm still working it out, but it has to do with Shakespeare's

writing for a theater without naturalistic presentation--David

Garrick's innovations were nearly 150 years away--where stylized

declamation was the mode. And so language carried the action,

both physical and emotional. Stage business was relatively restricted,

as were the visual cues that later would help us read a character.

Shakespeare had to get across the emotional tenor of his work

through language. This current production overruns language with

visual and aural prompts that seek to clarify meaning. Instead,

their appeal to our senses foreshortens the complexity. The play

of language has lost, is lost, to the production. Similarly, August's

pyrotechnic dialogue represents a loss of faith in language's

power to engage and move us. In that show, words are employed

as the equivalent of the weirdly aggressive strobe lights in Young

Frankenstein, a relentless assault on our ability to think

for ourselves, just as the large-type readings and technical effects

overwhelm Shakespeare's poetry and magic in this version of Macbeth.

When this production slows down--as when Macbeth untwists a cork

while unraveling his intentions--we are reminded that a simple

gesture can create a space in which the words can work on us,

and we can work on the words.

Ultimately, Malcolm's unsettling test,

where he reveals an unrestrained vision of human desire run amok,

seems the basis for the production values of this show. That the

production originated at the Chichester Festival Theatre before

moving to London's West End means it's not only on Broadway that

the hurlyburly's won. Rather than give our thoughts space to unfold,

Rupert Goold has joined Mel Brooks and Chicago's Steppenwolf Company

in following Malcolm's mock boast to "Uproar the universal peace."

On Broadway, When Malcolm then claims "there's no bottom, none,/

In my voluptuousness," a claim that provokes Macduff's warning,

"Boundless intemperance/ In nature is a tyranny," his words sound

less like moral corruption than like another showbiz formula.

Voluptuousness has won. And that brings

to mind William Wordsworth's strange, retrospective claim for

his poems in Lyrical Ballads (1798) that they originated

in an attempt to counteract what he called the "savage torpor"

of his times. He and Coleridge thought their poems, in which the

simple and the supernatural intersected, did not simply represent

feeling but could spark feeling--fellow feeling--in readers whose

senses had been dulled by the horrifying, overstimulating French

spectacle of liberty and fraternity resolving into tyranny. Readers,

Wordsworth suggested, needed space to recollect their human nature.

With that in mind, I went to see Tom Stoppard's Rock 'n Roll

a few weeks later, expecting to see a similar challenge by intemperance,

voluptuousness, and uproar to tyranny. At least Stoppard grapples

with the limitations of the sensual approach. Then I went home,

read The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and scratched my

head.