A Landscape for a Saint

By Robert Marx

["A Landscape for a Saint"

was originally published in a French translation by F. Maurin

under the title "Paysage pour un saint": Maurin, Frédéric

(ed.). Peter Sellars. Paris: CNRS Éditions, coll.

Arts du spectacle/ Les voies de la création théâtrale,

vol. 22, 2003, pp. 62-7. (Link: <http:www.cnrseditions.fr>

and <http:www.artsduspectacle.cnrs.fr>) This original English

language version of the essay appears here by permission of the

publisher.]

Throughout most of the 1990s, Peter Sellars was a leading

stage director at the Salzburg Festival. That plain statement

of fact is remarkable from an American perspective. In the USA,

Sellars is still known mostly for his early work, especially an

unorthodox cycle of Mozart and Handel operas. How did Sellars

jump from Americanized Mozart to central Europe's conservative

Salzburg Festival? And how did he come to begin work there with

Olivier Messiaen's Saint Francois d'Assise -- a supremely

difficult, monumental, and obscure twentieth century opera of

faith that had been left unstaged since its world premiere in

1983? The answer lies in events surrounding Salzburg's greatest

artistic upheaval since World War II--the seismic change of power

there that followed the death of conductor Herbert von Karajan.

No modern artist personified Austria's tradition of authoritarian

cultural rule as did von Karajan. His simultaneous leadership

of European orchestras and opera companies created an omnipotent

mid-century Vienna-Berlin axis in classical music, one that reached

at times to London and Paris, as well. Karajan's business empire

was so pervasive that he had an even greater impact on international

recording and broadcast media than on live performance.

The Berlin Philharmonic was Karajan's main artistic and economic

base, but his most important annex was the Salzburg Festival.

This legendary Austrian summer festival (founded in the 1920's

by stage director Max Reinhardt, poet Hugo Von Hofmannsthal and

composer Richard Strauss), was a mid-career acquisition in Karajan's

international portfolio. He controlled it for over three decades

as an absolute personal fiefdom and conservative bastion. In the

process, Karajan restored the Festival as one of post-war Austria's

most prominent national cultural institutions. Under Karajan,

Salzburg became, to an unprecedented degree, starry, chic, classical,

international, expensive, often brilliant, and a total reflection

of one man's taste. Karajan, who was born in Salzburg, ruled.

But even in conservative Salzburg there can be shifting winds

in art and politics. Native son von Karajan died in the summer

of 1989. Once gone, his cultural empire broke apart and for the

first time in decades the opportunity arose to create a new approach

for the institutions previously under his total control. In Salzburg,

a long-whispered need to open the Festival to a wider roster of

artists and repertory could be acted upon at last. A delicate

post-Karajan era began, despite the reluctance of Salzburg's influential

tourist industry (and its corporate patrons in multi-national

media and recording companies) to admit that the Great Man was

no longer among them.

To lead Salzburg across this rainbow bridge, the Festival's governing

board turned to a newsworthy foreigner with no previous connection

to Austria -- the Flemish producer Gerard Mortier, who was then

director of Brussels' Theatre Royal de Monnaie. This was an unexpected

left turn on the part of the Salzburg Festival's board, a decision

taken in such contrast to Karajan's legacy that in hindsight it

seems almost defiant.

During the 1980's, Mortier transformed the Monnaie into one of

Europe's most progressive opera houses. He was as devoted to new

visual interpretations of opera, and the dominance of stage directors,

as Karajan was towards German cultural tradition and the dominance

of star conductors. Mortier was also interested in American artists

and wanted to give them major production opportunities in Europe.

His greatest coup in this regard came in 1988. With grand self-confidence,

Mortier ended the Monnaie residency of the venerated Belgian choreographer

Maurice Bejart's Ballet Of The 20th Century, replacing

it with the then little-known modern dance troupe of American

choreographer Mark Morris.

Morris' controversial appointment in Belgium became Mortier's

calling card. Bejart was a Belgian institution unto himself, and

his dismissal from the Monnaie was denounced by local press and

audiences. But for Mortier this was a newsworthy and provocative

move that defined his taste, his production preferences, and the

kind of risk-taking talent he felt should lead an opera house

in the late 20th century. The Mark Morris Dance Group's residency

in Brussels created an international sensation for the Monnaie

and its management. Some initial outrage over Morris' (and Mortier's)

personal styles soon faded as a series of exceptional new dance

works (many still performed) were created by the young man who

would soon be acclaimed as the finest modern dance choreographer

of his generation. Seemingly overnight, Brussels' royal opera

house ascended to the list of important international theatres.

MORTIER AND SELLARS

The idea of bringing Mark Morris to the Monnaie originated with

Peter Sellars. Mortier was among the first to present this American

director's work in Europe, including productions of Sophocles'

Ajax in 1987, Handel's Giulio Cesare in 1988 and

the 1991 world premiere of John Adams' opera, The Death of

Klinghoffer. He bonded with Sellars, appreciated the young

director's ideas, and greatly valued his advice. Once Mortier

accepted the offer from Salzburg and prepared to leave Brussels,

Sellars was among the most essential artists he hoped to bring

along. In a move typical of both men's boldness, the defining

work they scheduled for Mortier's first Salzburg season (1992)

was a new production of what was probably the previous decade's

most challenging musical composition: Olivier Messiaen's only

opera, Saint Francois d'Assise.

An audacious contemporary choice, Saint Francois was

put forward as the symbolic centerpiece of Mortier's artistic

program --a work meant to push the Salzburg Festival beyond its

core, central-European focus on Mozart and Richard Strauss. A

profoundly spiritual and Catholic opera by a then-living French

composer, it would be staged by this much-debated American director

in the Festival's most indigenous venue--the Felsenreitschule,

a former Salzburg royal riding academy carved out of a rocky mountainside.

This was a typically provocative Mortier move, and the risks

were considerable for his new administration. The city of Salzburg

is an historic Catholic seat not known through the centuries for

its ecumenical outreach. A radical Saint Francois (which

might be expected from the director who set Handel's Giulio

Cesare in the Cairo Hilton) had the potential to challenge

conservative associations in the realm of religion, as well as

stage art. Even more concerned was Salzburg's politically influential

tourist industry, which did not look upon Sellars or Messiaen

as a major draw for its expensive hotels, shops and restaurants.

Nearby businesses were further outraged when Mortier actually

lowered the Festival's ticket prices a bit from their astronomically

high levels under Karajan, setting off the fear of a domino effect

that could reduce local profits.

Aside from the social and economic issues surrounding Mortier's

choice of Saint Francois, the planned production also

threatened one of the Festival's most profound, practical, and

familiar traditions: Salzburg's resident orchestra, the august

Vienna Philharmonic (Austria's potent international symbol of

musical superiority) would not be in the pit for Saint Francois

d'Assise. Appearing instead would be the upstart Los Angeles

Philharmonic. This American orchestra would play concerts as well

as Messiaen's opera as part of an unprecedented month-long Salzburg

engagement. The L.A. Philharmonic's music director, Finnish conductor

Esa-Pekka Salonen, would conduct.

Guest orchestras from Europe and abroad had long been part of

Salzburg's summer schedule, but as brief visitors only. Never

before had an orchestra from the USA or anywhere challenged the

Vienna Philharmonic's home-team supremacy by playing a combined

opera and concert season at the Salzburg Festival. The results

backstage were predictable. Amid an increasingly suspicious, highly

charged and typically Viennese political atmosphere, Saint

Francois d'Assise became the top symbolic and public offense

against Karajan's Festival Legacy. Before the opera even went

into rehearsal, elected officials, local hoteliers, and Vienna

Philharmonic musicians were opposed. This political breach grew

only worse over the decade of Mortier's aggressive artistic leadership.

For Peter Sellars, this rare opportunity for an American director

upon one of Europe's most famous stages brought him easy controversy,

but instant status. Now he was an unexpected star in the rarefied

world of international opera. Until then, Sellars was known primarily

for directing classic plays and only a few operas in the United

States -- in Boston and Washington, at regional theatres, but

especially at the Pepsico SummerFare Festival in Purchase, New

York. His "radical" versions of the three Mozart-Da

Ponte operas, presented in repertory at Pepsico and revived over

many summers, became his best-known productions.

These idiosyncratic and remarkably accomplished stagings of Cosi

fan Tutte, Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni,

performed by a cast of young Americans who could act as well as

they sang, were a revelation for what might be achieved in the

USA by producing opera outside the working conditions of its opera

houses. A considerable theatrical event in a small setting, these

energetic, deeply American productions were rehearsed over many

weeks, revived and revised each summer at Pepsico with few cast

changes, and honed to an extremely high level of ensemble. They

would have been impossible to create within the limited time allotted

to rehearsals at any conventional opera house in the USA.

Sellars'

work was unsettling to some critics and many musicians, primarily

(and simplistically) for his transposition of Mozart's operas

to American locales. (Cosi fan Tutte's stage set was

a remarkably realistic New England roadside diner designed by

one of Sellars' longtime collaborators, Adrianne Lobel, who also

created a high-rise luxury apartment setting for Le Nozze

di Figaro. George Tsypin designed a New York slum environment

for Don Giovanni.) While Sellars' stage images

were far from literal interpretations of the operas' libretti,

the contemporary characters and expansive emotions in these performances

were exceptionally true to the music and made for a compelling

operatic experience.

Sellars'

work was unsettling to some critics and many musicians, primarily

(and simplistically) for his transposition of Mozart's operas

to American locales. (Cosi fan Tutte's stage set was

a remarkably realistic New England roadside diner designed by

one of Sellars' longtime collaborators, Adrianne Lobel, who also

created a high-rise luxury apartment setting for Le Nozze

di Figaro. George Tsypin designed a New York slum environment

for Don Giovanni.) While Sellars' stage images

were far from literal interpretations of the operas' libretti,

the contemporary characters and expansive emotions in these performances

were exceptionally true to the music and made for a compelling

operatic experience.

Along with predictable criticism, Sellars also had articulate

champions, most notably The New Yorker's prominent music

critic, Andrew Porter, whose influential reviews hailed Sellars

as a major new artist and potentially one of the most important

opera directors of his time. Porter's enthusiasm, coming as it

did from America's leading music critic, gave Sellars a serious

reputation relatively early in his professional life.

Because the Mozart productions were performed by mostly Boston-based

singers who were not yet in the grip of international careers,

it was possible to tour Sellars' Mozart repertory as a unit. When

first seen on stage in Europe (including Vienna in 1989) and later

on television, these US stagings abroad established Sellars as

an unusual American talent whose work could resonate on the international

scene. Here was a director with perhaps some idiosyncratic ideas,

but obvious technique, musical sensitivity, vision, intelligence

and passion.

The attention given Saint Francois d'Assise when it

opened the 1992 Salzburg Festival (where it was reviewed by 280

critics) brought Sellars even more opportunities in Europe, and

soon the general momentum of his career reversed. By the mid-1990's,

he was better-known for work created outside the United States,

and almost nothing of his originated in America -- a situation

not unlike that of Robert Wilson in the 1970's and early 1980's.

Sellars' "exile" in Europe became a great loss for American

opera. The artistic promise and sophisticated production process

of his Mozart trilogy have yet to be repeated or fulfilled at

theatres in the USA.

MESSIAEN AND SAINT FRANCOIS D'ASSISE

Olivier Messiaen, along with Mortier and Sellars, hoped that

the new Salzburg staging of Saint Francois would give

his opera a second chance. The only previous stage production

had been its unsuccessful world premiere at the Paris Opéra

on November 28, 1983. On that occasion, the composer's stage directions

and somewhat naive visual conception were followed exactly. The

opera was given as a sequence of literal bible illustrations from

the life of Saint Francis, with set and costume designs derived

from paintings by Fra Angelico and Matthias Grunewald. The production

was created by Italian director Sandro Sequi, with set and costume

designs by Giuseppe Criolin-Malatesta. The conductor was Seiji

Ozawa, music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and the

outstanding Belgian bass-baritone, Jose van Dam, created the marathon

role of St. Francois. In general, Messiaen's opera was poorly

received. It seemed too theatrically passive, too introspective,

too uncomfortably religious for all but a specialist audience,

and in certain key sequences the opera's music composed for an

oversized orchestra and chorus was extraordinarily difficult.

Despite the Paris premiere's failure, Ozawa remained loyal to

the work, and in 1986 he performed excerpts from Saint Francois

d'Assise in concert with the Boston Symphony. Three of the

opera's eight scenes were given: #3 ("The Kissing of the

Leper"), #7 ("The Stigmata"), and #8 ("Death

and the New Life"). Peter Sellars attended one of these performances,

which, as in Paris, included the indispensable Jose van Dam as

St. Francois. From these concert performances came Sellars' desire

to stage the full opera.

By experience and instinct as much as personal taste, Sellars

had to take a far more metaphoric approach than that of the premiere

production team, and Messiaen had the self-awareness to know that

the Paris production's literal style should not be repeated at

Salzburg. He gave Sellars the authority to work more simply, with

abstraction, devising a bold and extremely theatrical intersection

of light, video and fragmented architecture, all to be placed

within the massive permanent structure of the Felsenreitschule's

tiered stone arcades and outer walls.

Plans

for the production moved forward, but the authenticity defined

by the composer's participation changed suddenly. Only a few months

before the first performance, in the spring of 1992, Messiaen

died. He had met with Sellars to prepare the staging, but was

gone before rehearsals began. Now the Salzburg production would

become more than an authorized new approach and second chance

for Messiaen's opera. It would be, unavoidably, an international

memorial to a great composer.

Plans

for the production moved forward, but the authenticity defined

by the composer's participation changed suddenly. Only a few months

before the first performance, in the spring of 1992, Messiaen

died. He had met with Sellars to prepare the staging, but was

gone before rehearsals began. Now the Salzburg production would

become more than an authorized new approach and second chance

for Messiaen's opera. It would be, unavoidably, an international

memorial to a great composer.

Saint Francois d'Assise was commissioned in 1976 by

composer/impresario Rolf Lieberman, then director of the Paris

Opéra. Messiaen was 67 years old, and revered as France's

greatest living composer and teacher of composition (Pierre Boulez

was his student). But he had never written for the theatre and

had not composed vocal music in over thirty years. Messiaen resisted

Lieberman's offer at first, believing that "there was no

way forward for opera after Berg's Wozzeck." But

Lieberman was persistent, and Messiaen, a deeply religious man,

came to see the commission as a potential new way to express his

bedrock Catholic faith in music.

Throughout his long life (which for decades included weekly service

as organist at the Church of the Trinity in Paris), Messiaen composed

music upon two fundamental themes: Catholicism and ornithology.

He notated and used thousands of bird songs from around the world.

For him, what more logical subject for an opera could there be

than Saint Francis? In his preface to Saint Francois,

Messiaen wrote, "I have always admired St. Francis. First,

because he is the saint who most resembles Christ, and also for

a more personal reason: he spoke to the birds, and I am an ornithologist."

Saint Francois is massive in all senses. It is scored

for an orchestra of 119, a chorus of 150, and contains over 4

hours of music. As inspiration and operatic precedent, Messiaen

may have been influenced by four related operas of historic importance

to French composers: the supremely epic Les Troyens of

Berlioz, Wagner's musically massive, sonically transparent, and

very Christian Parsifal, the inwardly passionate

Pelléas et Mélisande of Debussy, and Mussorgsky's

Boris Godunov, with its non-linear narrative.

Messiaen wrote his own libretto, basing it primarily upon scripture

and 14th century Franciscan accounts. The text's eight "Franciscan

Scenes," in three acts, suggest the "progress of grace"

within the Saint's life. It is a work of unquestioned spiritual

and historical acceptance, in which irony, psychological character,

and commonplace action are wholly absent. ("I included no

adultery or crimes in my opera.") Each scene portrays a pivotal

interior moment of personal faith and self-revelation. They are

separate offerings of transitional moments in St. Francis' growing

awareness and transformation into sainthood: his fearful cure

of a leper; his ecstatic sermon to the birds; his stigmata. Somewhat

fragmentary in structure, and without formal arias or conventional

operatic form, the work is closer to oratorio than opera. In a

review of Sellars' production, Paul Griffiths (Andrew Porter's

successor as music critic at The New Yorker) wrote that

Saint Francois "presents characters who are at the

service of the work, as priests and acolytes are at the service

of the drama they commemorate in a liturgy."

In the best sense, Saint Francois d'Assise is a "consecrational

festival play" (as Wagner called his Parsifal) that

is unsuited to repertory presentations, rushed rehearsals, or

quick consumption by an audience. Messiaen referred to it as his

"densest" composition -- a vast summary of his musical

style, personal belief, and joy in nature. The opera's long orchestral

passages convey a sense of sustained eternity through faith. Inherent

spirituality, physical scope, and complex technical difficulties

in Saint Francois (both on stage and in the music) made it a perfect

opera for Peter Sellars, whose spiritual interests and outlook

on his world in many ways resemble Messiaen's.

FINDING A NEW APPROACH TO SAINT FRANCOIS D'ASSISE

Sellars has referred to the life of St. Francis as a "benediction

and challenge," using words similar to those of the composer

to evoke ultimate joy in life through sacrifice. Both artists

approached their subject from similar vantages, avoiding any sense

of the tragic, rejoicing in the transformation of suffering into

hope, and reveling in the expression of their private beliefs

in public forms, despite the risk of rejection by audiences. Sellars

is himself religious, and especially in the years since he first

staged Saint Francois, many of his productions seem driven

by a quest for public communion, conjuring in modern terms an

ancient aura of performance as ritual. (In this regard, Sellars

is not unlike such modern predecessors as Peter Brook.)

With

hindsight, one can see Sellars' staging of Saint Francois

d'Assise (at Salzburg in the summer of 1992, then revived

in Paris at the Opéra de la Bastille in December 1992,

and again at Salzburg in 1998), as the first work in a quintet

of related Sellars opera productions about faith, self-sacrifice

and rebirth. These include a double bill of Stravinsky's Oedipus

Rex and Symphony of Psalms (Salzburg, 1994), Handel's

Theodora (Glyndebourne, 1996), a mixed program entitled Stravinsky

Biblical Pieces ("The Flood" and "Abraham

and Isaac," among other short pieces; Netherlands Opera,

1999) and John Adams' El Niño (based upon nativity

themes; Opéra, Paris, 2000).

With

hindsight, one can see Sellars' staging of Saint Francois

d'Assise (at Salzburg in the summer of 1992, then revived

in Paris at the Opéra de la Bastille in December 1992,

and again at Salzburg in 1998), as the first work in a quintet

of related Sellars opera productions about faith, self-sacrifice

and rebirth. These include a double bill of Stravinsky's Oedipus

Rex and Symphony of Psalms (Salzburg, 1994), Handel's

Theodora (Glyndebourne, 1996), a mixed program entitled Stravinsky

Biblical Pieces ("The Flood" and "Abraham

and Isaac," among other short pieces; Netherlands Opera,

1999) and John Adams' El Niño (based upon nativity

themes; Opéra, Paris, 2000).

Sellars described the libretto's scenes as "objects of contemplation,"

but theatre requires ongoing stage action -- or at least an audience's

perception of thematic forward movement. How can a stage director

bring life to an already static and visually minimal narrative

of four hour's duration? How can interior faith become explicit

to an audience without falling back upon the cliched biblical

"tableaux vivantes" approach of Saint Francois d'Assise's

failed world premiere?

The solution grew from the contrast of a spacious, extravagant,

and very modernist stage setting with the unadorned and humble

acts of faith played upon it. The costumes (by Dunya Ramicova)

for Saint Francis and the Franciscan brothers were plain to the

point of being drab. They wore simple, brown hooded robes. The

Singing Angel was not an imposing Renaissance winged being (as

in the original Paris production), but was costumed as a modest

and modern religious supplicant with a backpack -- perhaps a sacrificial

hospice attendant who would be lost in a crowd if not for a crystalline

singing voice. (The program suggested a connection to Dorothy

Day and her Catholic Workers Movement in the United States, which,

through social service and publications, addressed issues of poverty

and destitution.) The human imagery of these characters was utterly

modest. But they were surrounded by a stage setting of rare magnificence;

summits of natural, constructed and technological worlds that

were literally open to the night sky (the theatre's roof is retractable)

and framed by the massive rock arcades of the Felsenreitschule.

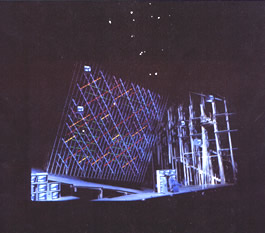

George Tsypin's towering set consisted of two immense structures

that filled the theatre's entire 130' stage width, but were divided

by a vast, vertical grid of fluorescent lights. On stage left

loomed a beautiful multi-story edifice that looked like the outline

of an unfinished cathedral. The chorus was most often seen on

high platforms inside this transparent symbol of human worship,

one whose bleached wooden design was divided into ledges and stairways

reminiscent of a Max Escher painting. Extending from the cathedral

towards stage right was a wide platform that grew in parabolic

form into a steep rake. (Tsypin described his set as built of

"...simple materials; organic, like flesh; real, naked, pure.")

Above

the ramp, which served as the main playing area, was the massive

square light grid with over 600 colored fluorescent glass tubes

placed in vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines. Messiaen said

that there were relationships between his music and color; that

he imagined different colors while he composed. The light grid,

which made its ever-changing electric shades and shapes insistently

visible, gave tangible form to the music's emotions and rhythms.

James F. Ingalls' lighting design was inventively sensitive to

the ebb and flow of the score, literally illuminating and emotionally

supporting the most dominant element of Messiaen's opera: his

orchestra.

Above

the ramp, which served as the main playing area, was the massive

square light grid with over 600 colored fluorescent glass tubes

placed in vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines. Messiaen said

that there were relationships between his music and color; that

he imagined different colors while he composed. The light grid,

which made its ever-changing electric shades and shapes insistently

visible, gave tangible form to the music's emotions and rhythms.

James F. Ingalls' lighting design was inventively sensitive to

the ebb and flow of the score, literally illuminating and emotionally

supporting the most dominant element of Messiaen's opera: his

orchestra.

Threading across and above the stage, hanging in the air and

moved around the acting areas in different configurations before

each scene, was another singular design element: forty video monitors,

each 35" across. During the opera, these showed continuous

video clips of natural vistas, flowers, a monk in pilgrimage,

and (of course) birds. The video used during the production, shot

by Sellars, became the production's most questionable, and criticized,

element.

SELLARS' LANDSCAPE

As integrated by this superbly unified stage design, the production

seemed like a theatrical "landscape" inspired by a very

different opera of faith: Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson's

Four Saints in Three Acts. Written in 1927-28, this opera's

mix of Stein's distinctive verse with Thomson's faux-naive melodies

has more wit than formal religion in it, and has long been an

iconic work for America's theatrical avant-garde. The continuing

fascination of Four Saints has much to do with its historic

production on Broadway in 1934, with an African-American cast

directed by John Houseman, choreographed by Frederick Ashton,

and sets by painter Florine Stettheimer that were made of cellophane.

Sellars considered reviving Four Saints for American

television in the early 1980's. Although this was never produced,

Four Saints had a continuing interest for him. In a Salzburg

program note, he mentioned "the spiritually transcendent

dramas of Gertrude Stein" as a predecessor to Saint Francois.

Stein intended that all the elements of movement suggested in

her Four Saints libretto be perceived simultaneously

-- like a cubist painting. The physical and musical were to be

one: "telling what happened, without telling stories,"

as she explained in an essay about writing for the stage. And

like a Stein libretto that explores relationships, not situations,

Sellars' staging of Saint Francois, unable to rely upon

conventional narrative, reveled in a Steinian "complete,

actual present" of simultaneous images and sounds of faith

spread across the cathedral, ramp, video monitors and light grid.

Perhaps also influenced by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill's

The Seven Deadly Sins, whose lead is played by both a singer

and a dancer (or again Four Saints, where the central

part of Saint Teresa is split between two singers), Sellars' divided

Messiaen's Angel into two contrasting roles: a Singing Angel (Dawn

Upshaw) and a Dancing Angel (Sara Rudner). Rudner, once a principal

dancer in Twyla Tharp's company, was costumed in the bright red

robes and cut-out wings of a Sunday school pageant -- a notable

exception and contrast to the subdued clothes of all the other

characters. Her oversized wings would have been at home in the

innocent fantasy of Four Saints. The divided character

of The Seven Deadly Sins must have been on Sellars' mind

during his preparation of Saint Francois. Only months

after the Salzburg premiere, in early 1993, Sellars created a

television version of the Brecht-Weill opera/ballet with Teresa

Stratas in the singing lead.

Sellars wrote in his Salzburg program note that "The lives

of the saints never go out of date. Their lives remain as touchstones

for every generation. Saints live again in our thoughts and our

hearts, but most importantly in our actions." This mingling

of interior faith with external action became Sellars' directorial

proof that Messiaen's religious vision was neither maudlin in

a public context, nor incompatible with inventive theatricality.

Sellars' controlled use of his cast and design team was the fulfillment

of all his stage experience, knowing when to be bold, when to

revel in mass effects, and when to sustain intimacy. His refined

stage vocabulary of hand and arm gestures was used to great effect.

At no point did these characters of the Catholic Church conventionally

cross themselves or genuflect. Instead, their choreographed hand

movements revealed impulses of the heart and mind--most movingly

when the Singing Angel suddenly appeared before a seemingly hopeless

Leper and with simple outstretched arms suggested the peace and

salvation of an unquestioned and inevitable world to come.

Sellars may have underused Tyspin's soaring cathedral in relation

to its overall scale and visual dominance, particularly a long

downstage staircase upon which no one set foot throughout the

opera. Why was it there? Perhaps this visual imbalance was the

result of limited stage rehearsal time with Vienna's Arnold Schoenberg

Choir, which remained mostly stationary in the transparent cathedral

structure, but sang the choral parts throughout with remarkable

dynamic shading and vitality.

George Tsypin takes a different view. He sees the unused staircase

as an artistic asset -- an example of Sellars' directorial discipline

and mystery. ("In Saint Francois... I had a complex

structure of an unbuilt cathedral and stairs shooting through

the whole thing and going into the sky. The stair was so prominent

you could not avoid thinking that somebody would come walking

down or up at some point. But Peter just ignored the stair and

made it so beautiful.... Having somebody on the stair would have

just made it be part of the usual scenery.") Tsypin makes

an eloquent defense, but when an audience wonders about the use

of unused space or scenery on stage, it loses focus on the work

being performed. The design takes on an aspect of extraneous beauty

for its own sake.

Before his sudden death, Messiaen hoped to be in Salzburg to

"prevent wrong notes in the music, but also .... in the lighting."

Given the massive variations in color and geometrical patterns

made possible by the fluorescent grid, its use was remarkably

consistent and restrained, often displaying just a few white or

red beams merely to outline a cross of light or emphasize with

massed color a particular sound coming from the pit. Only in the

opera's immense finale for full chorus and orchestra, marking

St. Francis' transcendence after death, did the entire light grid

show all its combinations in simultaneous grandeur. Messiaen had

noted that Christ's Resurrection should be "like an atom

bomb exploding"--an image the fully lit grid certainly matched

for Saint Francois. During his transfiguration in the opera's

final moments, every possible pattern of light and color came

into view on the grid as a fireworks display of pure light, matching

the orchestra's repeated sunbursts of sound.

Unlike the subtle fluorescent light grid, Sellars' perpetual

motion machine of forty video monitors was a failed experiment.

Originally, he hoped to include an oversized, outdoor Sony Jumbotron

in the production, but when rental and installation costs proved

excessive, the design was changed to deploy many smaller video

units, most of which were suspended above the stage at various

random heights.

Upon first sight, the hung monitors' artful, asymmetrical placement

over the vast Felsenreitschule stage was startling, and the projected

videotape added extra color to the overall design. But the multiple

images of flora and fauna soon became decorative and sometimes

irritating, with constant video flickering due to short takes

and busy editing. Only in Saint Francois' death scene did the

cross-cutting video stop. The overall effect undermined the rigorous

atmosphere of an otherwise disciplined production. Video and live

performers rarely mix on stage. However conceptually interesting,

the results here were distracting. Like an awkwardly positioned

supertitle system, the video installation pulled focus from the

live stage action and too often looked like home movies played

on a continuous loop.

Somewhat more successful and integral to the actual performance

of each tableau was the placement of a dozen or so movable video

monitors on the stage floor. Piled on top of each other, or threading

in a line across the wide stage, these monitors (reconfigured

before every scene by stagehands) became beds or walls, and defined

precise spaces, such as the window through which the Angel arrives.

Although they showed the same simultaneous video clips as the

monitors hung above the stage, the floor monitors seemed to be

involved with the action and became less distracting than those

floating on high.

In interviews, Sellars explained his reasons for using continuous

video in Saint Francois: That the monitors would evoke

traditional stained glass in contemporary form, functioning like

cathedral windows to provide narrative imagery above and behind

a performed "service"; also, that it would create a

generalized "hypnotic and intense" effect. Sellars had

managed to film all but four of the birds whose songs are cited

by Messiaen in the score, and through video brought them onstage

in convincing form, respecting Messiaen's ornithological passion.

But Sellars--despite his fascination with film and video--is not

a distinguished artist behind a camera. His powerful understanding

of theatre and his commanding stage technique have not yet translated

into a similar command of media. Up to now, Peter Sellars the

stage director and Peter Sellars the film director have been incompatible.

There was also a mechanical disadvantage to the video installation.

Long pauses were necessary between scenes while the stagehands

in street clothes unplugged, repositioned, and replugged the video

units placed on the stage floor. At both performances I saw during

the production's 1998 revival in Salzburg, many audience members

assumed that a technical problem caused the production to stop

in its tracks while the cables and monitors were reset. Only when

the electrical crew reappeared after each scene did it become

clear that this was intentional. Given the break in emotional

momentum and mood caused by those awkward, lengthy pauses, the

video design's mechanical challenge became an emotional liability.

The one exception came in Messiaen's 45-minute tableau of St.

Francis' sermon to the birds. Here the video installation truly

enhanced the opera as Saint Francis wandered among monitors scattered

about the steep ramp like rocky outcroppings in a lush field.

The quickly alternating video images, on stage and above, were

timed perfectly to the score, handsomely and sweetly showing the

birds to whom St. Francois preached. At last, the video fulfilled

Sellars' artistic goal. Through media, he created an electronic

aviary to bring Messiaen's rich colony of birds onstage. Sellars

tends to be at his best when directing an opera's most challenging

scenes. (This was certainly true in his production of Le Nozze

di Figaro, where the opera's fourth act, a theatrically difficult

sequence of five arias with no intervening ensembles before the

finale, was compelling and far better staged than some of that

opera's more conventional passages.) Saint Francois' static, but

impassioned and very long sermon to the birds contains the opera's

most complex and extended music. It seemed unplayable at the Paris

world premiere. At Salzburg, it was a musical and dramatic highpoint.

From

"The Sermon to the Birds" (number six of Messiaen's

eight tableaux) the production moved to its purest and most emotional

sequence, and also one of its simplest: the stigmata scene, where

Sellars' minimal staging again gave life to the raw power, ecstasy

and conviction of Messiaen's score. Stretched prostrate upon the

ramp's highest point, Saint Francis was "pierced" by

five light beams projected not from a massive cross, as Messiaen

wrote in his stage directions, but from small hand lamps held

by the Franciscan brothers: four beams touched the end of each

of the Saint's limbs, while a fifth "pierced" his side.

Across the Saint's hands and feet the Dancing Angel gently poured

liquid that dripped in a red line over his body and then straight

down the steeply raked stage. This simple image of white light

and flowing red liquid (all in straight lines that grew in time

to Messiaen's expansive music) made the Saint's sacrifice to his

faith emotionally magisterial and physically beautiful.

From

"The Sermon to the Birds" (number six of Messiaen's

eight tableaux) the production moved to its purest and most emotional

sequence, and also one of its simplest: the stigmata scene, where

Sellars' minimal staging again gave life to the raw power, ecstasy

and conviction of Messiaen's score. Stretched prostrate upon the

ramp's highest point, Saint Francis was "pierced" by

five light beams projected not from a massive cross, as Messiaen

wrote in his stage directions, but from small hand lamps held

by the Franciscan brothers: four beams touched the end of each

of the Saint's limbs, while a fifth "pierced" his side.

Across the Saint's hands and feet the Dancing Angel gently poured

liquid that dripped in a red line over his body and then straight

down the steeply raked stage. This simple image of white light

and flowing red liquid (all in straight lines that grew in time

to Messiaen's expansive music) made the Saint's sacrifice to his

faith emotionally magisterial and physically beautiful.

At the 1998 Salzburg Festival, the cast was exact and revelatory,

particularly Jose van Dam, who repeated his remarkable performance

from both the Paris world premiere and the 1992 Salzburg season.

Van Dam performed this marathon part with profound dignity, beauty

of tone, and clear diction, along with dramatically convincing

religious fervor, seeming to project St. Francis' self-doubt and

faith towards a place beyond himself. His characterization was

at once restrained and magnificent. American soprano Dawn Upshaw

(also returning from the 1992 Salzburg cast) showed yet again

how different and more complete an artist she is when she works

with Sellars. Angels are meant to be ethereal, and Upshaw was,

while also utterly believable in her down-to-earth service towards

all who came before her.

Both these performances showed the rich possibilities for opera

when otherwise "conventional" singers (albeit important

musicians) work with Peter Sellars. He is underappreciated as

a teacher and coach. Opera stars, as much as the young cast of

Sellars' Mozart cycle, transform themselves with his guidance.

SALZBURG AND BEYOND

Predictably, the 1992 opening night Salzburg Festival audience

applauded the singers and musicians, then booed Sellars and his

production team. (The Los Angeles Times' review carried this headline,

"The Verdict: Salonen Ja, Sellars, Nein.") Much the

same happened at Salzburg's 1998 revival, conducted this time

by Kent Nagano with his Halle Orchestra from England replacing

the L. A. Philharmonic and Esa-Pekka Salonen. (Like Jose van Dam,

Nagano had a long association with Messiaen's score. He assisted

Ozawa at the world premiere, conducted one performance during

the original Paris run, and led concert performances of Saint

Francois in Europe and America during the 1980's.) The boos

came mostly from Salzburg claques that were still opposed politically

to this singular production--the most symbolic offering of Mortier's

nouveau regime, now brought back for a second season. The claque

departed after a raucous first curtain call, while the large audience

that remained in the Felsenreitschule gave a long ovation to everyone

onstage.

Peter

Sellars' audiences--as much as Sellars himself--need the opportunity

to experience his productions on a regular basis. His repertory

should be repeated and revised over years, as his Mozart trilogy

was both at Pepsico SummerFare and on tour. Mortier showed great

courage by reviving Saint Francois d'Assise in 1998.

Announced revivals in Paris after the production's 1992 transfer

from Salzburg were undone by a change in management at the Opéra

de la Bastille. Although there were discussions about recreating

the production in Los Angeles and New York, nothing came of those

plans. Eventually, the US stage rights to Saint Francois d'Assise

were obtained by the San Francisco Opera, and the American premiere

took place there in September 2002. This was the centerpiece of

American producer Pamela Rosenberg's first season as the San Francisco

company's General Director, but she chose to give Messiaen's opera

in an entirely new production created by German artists.

Peter

Sellars' audiences--as much as Sellars himself--need the opportunity

to experience his productions on a regular basis. His repertory

should be repeated and revised over years, as his Mozart trilogy

was both at Pepsico SummerFare and on tour. Mortier showed great

courage by reviving Saint Francois d'Assise in 1998.

Announced revivals in Paris after the production's 1992 transfer

from Salzburg were undone by a change in management at the Opéra

de la Bastille. Although there were discussions about recreating

the production in Los Angeles and New York, nothing came of those

plans. Eventually, the US stage rights to Saint Francois d'Assise

were obtained by the San Francisco Opera, and the American premiere

took place there in September 2002. This was the centerpiece of

American producer Pamela Rosenberg's first season as the San Francisco

company's General Director, but she chose to give Messiaen's opera

in an entirely new production created by German artists.

Although unseen in the USA, the Salzburg staging of Saint

Francois established Sellars on the international scene and

led to new assignments in London, Paris, Amsterdam and other cities.

The next summer at Salzburg, in 1993, Sellars directed Aeschylus'

The Persians as part of the Festival's revitalized drama

program (led, at Mortier's invitation, by German director Peter

Stein). Stravinsky's Oedipus Rex and Symphony of

Psalms followed in 1994, and Ligeti's Le Grand Macabre

in 1997.

Saint Francois d'Assise also led to an unanticipated

new collaboration for Sellars: Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho

saw Saint Francois during the 1998 revival and was inspired

to write her own opera, a form that (like Messiaen before

Saint Francois) she had not considered previously. Commissioned

by Mortier for Salzburg, Saariaho's L'Amour de Loin,

staged by Sellers with sets and lights by Tsypin and Ingalls,

was a major success at the 2000 Salzburg Festival, and in November

2001 the production was brought to the Châtelet in Paris.

L'Amour de Loin was Peter Sellars' final work at Salzburg

before Mortier resigned from the Festival in the summer of 2001.

There had been too many years of growing political intrigue, hostile

criticism and antagonism with the board and audiences. After a

decade of Mortier's fractious leadership (which even included

a courageous public airing of the Festival's past Nazi associations),

Salzburg wanted a rest--and at least a partial restoration of

Karajan's profitable tradition, glamour and comfort.

Peter Sellars is not expected to return to Salzburg soon, but

L'Amour de Loin has become the vehicle for reintroducing

him as an opera director in the USA. In the summer of 2002, he

revived Saariaho's opera at the Santa Fe Opera in New Mexico.

Santa Fe's quasi-outdoor stage required the redesign and simplification

of George Tsypin's set, but when Sellars' production comes to

the Metropolitan Opera House as part of New York's Lincoln Center

Festival in July 2004, it will be seen in the set Tsypin created

for the Châtelet in Paris. In this version, Tsypin's Islamic-inspired

designs (which required flooding the entire Felsenreitschule stage)

are translated with remarkable beauty to the conventional proscenium,

fly space and stage depth of a classic opera house. Perhaps, with

these American engagements for L'Amour de Loin and also

John Adams' El Niño (Los Angeles and New York,

2003), Sellars will at last have production opportunities in the

United States that match the scale and importance of those he

has had abroad.

In his Salzburg Festival program notes, Sellars wrote that "St.

Francis, by refusing to engage in oppositional politics, transformed

the Catholic Church -- not by attacking it, but simply by living

differently and letting people notice for themselves what the

difference could mean." That comment might serve as a description

of Sellars' own career in opera. An itinerant artist without a

home theatre, he has "lived differently"--working repeatedly

in many countries and theatres with the same designers, performers,

and production staff as opportunities arise. (Sellars' longtime

stage manager, Keri Muir, has learned to "call" his

productions in four languages so that she can supervise his tours

and revivals with stage crews from different nations.) These colleagues,

an ensemble whose careers and lives keep intersecting due to Sellars,

form what one might informally call the world's most prestigious

touring opera company.

While hardly any of this ensemble's work of the past decade has

been seen in the USA, nearly all the collaborators are American.

How thankless and odd, but exciting and ironic, that at Austria's

conservative Salzburg Festival a pre-eminent American director,

American designers, an American stage manager, an American production

staff and a largely American cast could so brilliantly realize

an impossibly challenging contemporary French opera that they

would never have the opportunity to perform in America.

PHOTO INFORMATION (from top to bottom)

1. Olivier Messiaen's Saint Francois d'Assise, directed

by Peter Sellars.

2. Mozart's Cosi fan Tutte, directed by Peter Sellars.

3. Peter Sellars, Gerard Mortier, Kaija Sariaho, Amin Maloufin

at the Felsenreitschule.

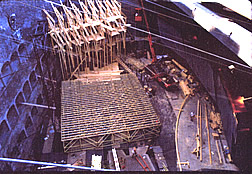

4. George Tsypin's set for Saint Francois d'Assise under

construction at the Felsenreitschule.

5. The light grid in Tsypin's set.

6. The stigmata scene with dancing angel and two hand-held lights

in Saint Francoise d'Assise.

7. Handel's Theodora, directed by Peter Sellars.

[Robert Marx is a New York foundation director, essayist

and theatre producer who has collaborated with Anne Bogart, Robert

Woodruff, Peter Hall and Richard Nelson.]