Inviting the Audience

Phelim McDermott in conversation with Caridad Svich

[Phelim McDermott has been directing

and performing for more than twelve years. His first work was

for dereck dereck Productions, which he co-founded with Julia

Bardsley. He performed in Cupboard Man, a solo show for

which he won a Fringe First Award. He then co-directed and performed

in Gaudete for which he won a Time Out Director's Award.

During 1996-97 he directed A Midsummer Night's Dream for

the English Shakespeare Company, which won a T.M.A. Regional Theatre

Award for Best Touring Production. He co-founded Improbable Theatre

company with Julian Crouch, Lee Simpson and producer Nick Sweeting

in 1996. The company is distinguished for its improvisational

approach to text and innovative designs. Improbable's productions

include 70 Hill Lane, Lifegame, Coma, and The Hanging

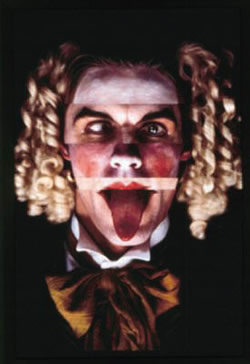

Man. With Julian Crouch McDermott co-directed Shockheaded

Peter, a junk-opera collaboration with The Tiger Lilies, for

Cultural Industry. He has worked with Peter Greenaway and was

a co-deviser of The Masterson Inheritance on BBC Radio

4. This conversation was held as Improbable's adaptation of Theatre

of Blood was preparing to open at The Royal National Theatre,

and Shockheaded Peter was about to return to New York

for an Off-Broadway run.]

CS: Have puppets always been a part of

your theatrical vocabulary?

PM: Pretty much, even before I met Julian

Crouch and we started working together. I was at the Leicester

Haymarket doing a kid's show called The Ghost Downstairs,

which is kind of an inverse version of the Faust story, written

by Leon Garfield, who is a children's book writer. The story is

about a lawyer who meets a man downstairs who is probably the

devil. The devil says to him, "I'll give you all the riches in

the world if you give me seven years off of the end of your life."

The lawyer agrees to this but in drawing up the deal thinks about

swindling the devil and decides that instead of selling him seven

years off of the end of his life, he'll sell him seven years off

of the beginning. Well, the deal is struck, and he does get all

this wealth, but slowly he begins to be haunted by the ghost of

a little boy, who turns out to be his own childhood coming to

haunt him. We used a puppet for the boy. At the same time Julian

was doing The Little Prince with great, big-scale puppets,

and I became intrigued. I was invited to direct a production of

Dr Faustus and I knew I wanted the Seven Deadly Sins

to be puppets, so I asked Julian if he wanted to work on it, and

that's how we ended up working together.

Improbable Theatre started in 1996 with

70 Hill Lane, but Julian and I had been working together

for a long time. We had actually resisted forming a company for

years because we didn't want to scratch money together and do

all that. So, ours was a backward route. We were working in the

repertory companies doing big shows and when we formed Improbable

we went back to doing small shows, partly because we wanted to

do work that was more personal again while we kept the bigger-scale

projects going.

CS: 70 Hill Lane is very personal,

and you have traveled with it quite a bit. How does the connection

with the audience occur when you have toured with it?

PM: We took the piece to Egypt where the

audience was largely non-English speaking and it had an extraordinary

response, which surprised me. On some level, it is about the visual

element of the piece and about the imagination and the puppetry,

but I think it is also about that connection, if people are willing

to relate to the person who is talking. There are studies where

it's been said that 10% of our communication is verbal, whereas

the rest is primarily visual. In Egypt or in Syria, where we also

performed 70 Hill Lane, people are surprised and shocked

that someone is speaking directly to them--and also that not only

will an actor speak directly to the audience as part of the show,

but that if something happens in the audience, the performer will

to respond to it spontaneously--unscripted--right then and there.

People

say that Shockheaded Peter or other work that we do is

really new, but I don't think it is. It's quite simple, and old-fashioned.

It's just storytelling: talking to people and telling stories.

I think what is different is that we are prepared to use anything

to tell the story. I like interacting with materials and seeing

what they can do and how they can speak. 70 Hill Lane

was an exploration of that. In fact, one of the decisions we made

early on was that we were going to make the house from newspaper

stuck onto cello tape, so we'd build it like a Wendy house. Then

we realized that just the tape in the space was magical, and strange,

because it was there and it wasn't there, and it left a lot of

space for people to read into it, so they could see their own

house. We talk about our sets and how we like to have a gap in

them: a gap between what you're saying it is and what you're seeing.

So, you say it's a tree but it is obviously a cardboard tree,

so the audience plays the game with you and says, "We'll believe

it's a tree." We also talk about our sets as being like puppets.

The story of the set in the show is as important as the story

of the actors performing on it.

People

say that Shockheaded Peter or other work that we do is

really new, but I don't think it is. It's quite simple, and old-fashioned.

It's just storytelling: talking to people and telling stories.

I think what is different is that we are prepared to use anything

to tell the story. I like interacting with materials and seeing

what they can do and how they can speak. 70 Hill Lane

was an exploration of that. In fact, one of the decisions we made

early on was that we were going to make the house from newspaper

stuck onto cello tape, so we'd build it like a Wendy house. Then

we realized that just the tape in the space was magical, and strange,

because it was there and it wasn't there, and it left a lot of

space for people to read into it, so they could see their own

house. We talk about our sets and how we like to have a gap in

them: a gap between what you're saying it is and what you're seeing.

So, you say it's a tree but it is obviously a cardboard tree,

so the audience plays the game with you and says, "We'll believe

it's a tree." We also talk about our sets as being like puppets.

The story of the set in the show is as important as the story

of the actors performing on it.

CS: How much turn-around do you allow between

the creation of pieces? Is it open or do you have a set time-table?

PM: It's open out of necessity because

we do not get revenue funding. We are project-funded, so if we're

not doing a show, we are not making money for Improbable. Things

which have kept me going have been: Shockheaded Peter,

and doing improvising gigs at The Comedy Store, which is where

Lee Simpson (co-founder of Improbable Theatre) makes his wage.

Julian does other design and directing jobs, which is healthy

for all of us, but also presents difficulties. Our office is paid

for basically by touring in the US. This also comes down to the

decision about how we work, because if you become revenue-funded

then you have to produce a certain number of shows, etc. One of

the problems, I would say, is that we had an initial burst of

shows--70 Hill Lane, Animo, Lifegame, Coma, Sticky (which

is an on-going large-scale project) and Spirit--but we

don't get much time to do any kind of seeding or dreaming, which

is so important. I think it's especially difficult now because

you can get on a treadmill and just do and not think. The good

thing is that we're not comfortable with being comfortable. We

recognize this is a company, so if we're going to do something,

we have to be interested in it.

CS: How did the idea for The Hanging

Man come to be, and how did it morph into what it is now?

PM: The initial idea for the story came

from Julian Crouch. He had just been working on a TV job from

which he got sacked, and he was driving in his car, feeling pretty

angry, and the idea for a story came into his head: a man tries

to hang himself, but he's so inflexible that he can't actually

do it. That became the key to the whole piece. We also decided

we wanted to do a new show that had the scale of Shockheaded

Peter but was more like our Improbable shows, which have

a more intimate quality. I talked about the idea of wanting to

do something that was more vulnerable and less showy. It was important

to me that the new piece had more contact with the audience, where

the performers could be themselves. The other idea was that we

wanted to start putting together an ongoing ensemble that would

learn how to work the way that we work, so in effect our work

could tour as it has done but we wouldn't have to tour with it

as performers. So, we had a couple of development periods for

The Hanging Man. One was at the Walker Art Center in

Minneapolis, and the other was at the Wexner Center for the Arts

in Columbus, Ohio. Then we had about three weeks with an initial

workshop with actors.

CS: Actors were not involved at every step

of the development?

PM: No, just in the three weeks after we'd

made some decisions as a company about the show, its shape, and

so on. The first two development periods were with Lee Simpson,

Julian Crouch, sound designer Darron L. West (of SITI company),

and myself. We sat in a room together and talked about what we

were going to do. Julian found a painting by Tiepolo, which was

of a group of Pulchinellos. What's interesting about the painting

is that all the Pulchinellos are the same. They're all wearing

tall hats, sitting around a cooking pot and cooking gnocchi. They're

in half-light, yellow-light, very beautiful. The painting is very

atmospheric and languorous. It's not in a performance-mode. It's

as if the Pulchinellos were off-duty. We liked what they looked

like, because they reminded us of ourselves: artists hanging around

the outskirts of a city, outcasts from the theatre.

So we then spent three weeks with a group

of actors, and Julian made some Pulchinello masks, and we explored

ideas and shapes for three weeks trying to find out what the story

was, and what these characters were like. We then decided that

the guy who wants to kill himself is an architect, who has done

a great project. He's made a beautiful cathedral, which is a great

success. And the funny thing is, he made the cathedral without

really thinking about it. The guy who was designing it had died

and he had to take over the project, so he just kind of made decisions

really quickly. And then someone says, "Okay, you've done this

great building and we want you to do another. Here's all this

money. You can do whatever you want." And he starts this new project,

and when it's half-built, he realizes that it's not working. It's

a failure. And rather than deal with the issue of it being a failure,

he decides to kill himself. He decides to hang himself inside

this unfinished cathedral. But it doesn't work. At which point

Death turns up and says, "Wait a minute, it's not that easy. Just

because you had this thing happen you think you can just use me?

You've never ever thought about me. You've never had a relationship

with me. You've got to hang around for a while and deal with me."

CS: And Death stays present.

PM: Death's present in the show. We wanted

to create a modern mystery play. It's interesting because since

creating the show, a number of people have said, "Oh you know

the story about . . ." Apparently, there's some story about an

architect who did hang himself in his own church. But for us,

it's a story about us as an ensemble, about our journey, and where

we were at the time of making the piece.

An

interesting thing that happened in the process of The Hanging

Man was that we decided to have a script before we went into

proper rehearsal. That's something we hadn't really done before:

write everything out. But Julian decided he wanted to write a

play. So, he went away and wrote a script, after which Lee said,

"We're not very good at doing plays. We're much better at adapting

things. So Lee suggested we would create a document--a historical

document written as if someone three hundred years after the fact

was researching this myth of the Hanging Man. It was a mock historical

document that then became a script, which we adapted.

An

interesting thing that happened in the process of The Hanging

Man was that we decided to have a script before we went into

proper rehearsal. That's something we hadn't really done before:

write everything out. But Julian decided he wanted to write a

play. So, he went away and wrote a script, after which Lee said,

"We're not very good at doing plays. We're much better at adapting

things. So Lee suggested we would create a document--a historical

document written as if someone three hundred years after the fact

was researching this myth of the Hanging Man. It was a mock historical

document that then became a script, which we adapted.

It was weird because in order to get to

a point where we were happy with a script, and having one in the

first place, we had to adapt our own. We had to pretend we were

someone else. It was an interesting process that we ended up with.

In the U.K. we put a bit of that mock document into the program,

and people said, "Oh, it's a real story? It's not a myth?" We

created a myth. A new myth.

CS: Have you been working with the same

group of actors throughout the piece's development and touring?

PM: No. After the first workshop we kept

one of the actors and then we re-cast. So we had a whole new group

of people, partly because I wanted to address the issue of getting

the actors to bring themselves to the process in a very direct

way. We kind renegotiated the deal with the performers and said,

"Look, it's going to be like this: You're going to have to be

yourselves at certain points in the show, and we want you to know

that that's going to be a challenge." So, there are sections of

the show where they are themselves and not characters or figures.

There are sections of the show that are descriptions of their

own dreams. And there are sections where they talk about their

own death fantasies: they imagine how they'd die, what it would

be like, and what would happen afterwards. That's the bit of the

show that changes each night.

CS: I'm interested in the central act of

suspension in the piece. The architect character is hanging for

the entire length of the show. Physically, how does that work?

PM: In terms of the actual, physical structure

of the set, one thing we wanted to make sure is that whatever

technology we used had to be seen. That's important to us in our

work. Phil Eddols (the co-designer on this show) has something

of a medieval technological mind. He knows about pulleys and weights,

etc. When we were workshopping at the Walker Art Center, I found

a beautiful French book of architectural drawings and co-designer

Phil got very inspired by these pictures. For the show, he created

a pulley system that is human-driven.

It's not as physical as we imagined it

would be, but it's pretty clear that it's human-operated. It's

a pulley system that goes up and down, and also trucks back and

forth, so that's the leeway that you've got. You see the structure

also around all this stone. There's something exciting about the

unfinished nature of it, about an unfinished show playing at BAM!

I think that's essential to Improbable's work. We've always felt

that things are unfinished until the audience turns up. Things

are porous, therefore, so that the audience can partake in the

show.

CS: I've been obsessed with the question

of virtuosity in theatre, especially because it has been an ongoing

question with a lot of the artists I work with. I feel that sometimes

you go to a theatre to watch a virtuoso, to watch superb technique,

to watch a company craft something. But at the same time that

can't be the end-product.

PM: I think that you go to the theatre

to see people be super-human. For me, the exciting thing is to

see potential: to see someone reaching into and outside of themselves

in the moment. That's what I think skill is for: to create the

space and the potential for something amazing to happen. Ultimately

the problem of artistry is that you can't make it happen. All

you can do is create the situation where potentiality exists.

CS: I've been thinking, as you've been

speaking, about this agreement that you say you have with the

audience. What happens in the moment where you offend the audience?

I happen to think sometimes that's valuable. But how do you regain

the audience once you've crossed that line? Are there strategies

you have for doing that?

PM: There's the bit of The Hanging

Man where the performers talk about their death fantasies.

In rehearsals we played a lot with using mini-disc recorders recording

text and then playing it back, and then repeating it exactly as

recorded. We then played with the actors recording each other's

death fantasies, as well as their own. I wanted to find out what

it was like to do that in front of an audience. Our shows are

basically quite accessible, but this tiny transgression, this

section on death fantasies, tends to put people off. I think it's

often the frame that offends, and a frame can be more offensive

than questionable moral content.

CS: Shifting gears a bit, you've received

a NESTA fellowship to continue your research work especially in

regard to Arnold Mindell's conflict-resolution methodologies and

how to use them in the theatre. What does this kind of open dream

time allow you to accomplish now?

PM:

I'm collaborating with Jude Kelly, from West Yorkshire Playhouse,

and she has created this amazing space in London called Metal.

It's an arts space. And what's extraordinary about it is it is

a space to facilitate creativity. You walk in, and you're in this

brick, stripped-down room, and the most important thing in the

room is a big wooden table and an Argo cooker. At the center is

a community space at which to have meals. And then there is the

big, tall structure, which is the office, and there's a gallery,

and at that other end they've got the flats for artists to stay

in, to be artists in residence, to come and create something for

the gallery. But they also have this space to have a meal in,

with people they would happen to network with, brainstorm with.

So it's actually a beautiful space and idea, because it's about

creating something that supports the creative process in a whole

new way. She's created a home for artists to come and to be mentored

in. While I'm at Metal, I will create forums for people in the

theatre community to process issues that don't get processed,

voices that don't get heard, and explore what those issues are.

For me, these forums are an attempt to process those issues, rather

than just have a conversation. They're an attempt to create some

fluidity and give people a chance to say things, but also to free

up people stuck in identified roles. Mindell's new book is The

Deep Democracy of Open Forums, and it's basically about how

to run and create forums, and we'll be using the book as the basis

for our work.

PM:

I'm collaborating with Jude Kelly, from West Yorkshire Playhouse,

and she has created this amazing space in London called Metal.

It's an arts space. And what's extraordinary about it is it is

a space to facilitate creativity. You walk in, and you're in this

brick, stripped-down room, and the most important thing in the

room is a big wooden table and an Argo cooker. At the center is

a community space at which to have meals. And then there is the

big, tall structure, which is the office, and there's a gallery,

and at that other end they've got the flats for artists to stay

in, to be artists in residence, to come and create something for

the gallery. But they also have this space to have a meal in,

with people they would happen to network with, brainstorm with.

So it's actually a beautiful space and idea, because it's about

creating something that supports the creative process in a whole

new way. She's created a home for artists to come and to be mentored

in. While I'm at Metal, I will create forums for people in the

theatre community to process issues that don't get processed,

voices that don't get heard, and explore what those issues are.

For me, these forums are an attempt to process those issues, rather

than just have a conversation. They're an attempt to create some

fluidity and give people a chance to say things, but also to free

up people stuck in identified roles. Mindell's new book is The

Deep Democracy of Open Forums, and it's basically about how

to run and create forums, and we'll be using the book as the basis

for our work.

CS: It sounds amazing and necessary. Especially

now because people seem so fragmented and afraid, because the

economy is so horrible and with every decision you make as an

artist it's like, "Oh my God, why am I doing this? How is this

going to be received? Am I going to lose all the people who supported

me before?" All of that. I'm very curious about the new Improbable

piece, about the critic.

PM: Theater of Blood. It's one

of those late-night films that I saw when I was a teenager. It's

a fantastic, quite camp film with Vincent Price in it, which has

a terrible ending. But it has this wonderful central idea that

there's a kind of fantastic old Shakespearean actor, who's famous

for doing these Shakespearean roles. He gets rejected at this

awards ceremony and then goes into this room where all the critics

are, the critics' circle, as it were, and he commits suicide.

And of course, he hasn't died. What then happens is, slowly, one

by one, the critics get killed off. Someone's murdering these

critics. But they're each murdered in these horrible ways that

are very similar to Shakespearean deaths. So basically, as this

actor, he takes revenge. He re-writes The Merchant of Venice.

He feeds someone their own poodles in a pie. It's almost cheesy,

but it has got the potential to be both entertaining and scary

and open up quite an interesting discussion about criticism and

critics.

CS: Are you thinking of making it contemporary?

PM: It might be interesting to keep it

set in kind of a 1970s style. But there's one bit of me at the

moment that thinks theatrically it might be interesting to explore

different theatre styles: 1980s RSC, Butch, Alan Howard, mid-nineties

physical theatre. One of the central debates in the Theater

of Blood is the concept of the virtuoso, the classical Shakespearean

actor, and what happens to virtuosity and its perception over

time.

CS: Wearing many hats sometimes confuses

people. They don't quite understand how you can shift your energies

around as an artist. It is something I do all the time because

I am simply following my interests and being true to my heart,

but I know the question often arises: "Aren't you supposed to

do just one thing?"

PM: Well, it scares people because they

can't relate to you in a particular way so they know what you

are. For me the development of a person is that you become flexible

about those roles. You can be all those things. And the boundary

of what you do and can do, your sense of yourself, grows and changes

all the time. It is also the way I like to think about shows and

about work. It is a constant journey. Each person has their own

version of how things get formed, and how you keep breaking out

of that eggshell.

CS: I think the hybrid form is the 21st

century form, at least in theatre, where an actor, a dancer, a

DJ, a film, can all co-exist in one piece of work. It is part

of the world we live in. At the same time this world which we

say is shrinking and moving ever so fast and incorporating all

is ignoring countries that are not part of the shrinking, globalized

marketplace. I think artists have a responsibility to keep an

awareness that there are other people on the planet who aren't

part of the driven, corporate machine, and if enough artists are

alive to those voices which are being ignored or left behind,

the voices will come into the work and maybe communicate something

else to an audience, because it is easy to think this is the only

kind of world we live in and necessary to be reminded otherwise.

PM: The same things that present opportunities

also mean people will be left behind and marginalized in different

ways. Arnold Mindell talked about it when we worked on Coma.

When someone goes into a coma, they get treated as if they are

not there, as if they are invisible, they don't exist, they may

as well be dead, and people won't go near them, quite literally.

What Mindell says the comatose person is doing is that they are

in a deep state which is the kind of state shamans would go into

to do deep work for the community. He also says one of the reasons

people get stuck in comas is that everyone around them is denying

their experience. Mindell tells a story about a man he worked

with who had leukemia and they were ready to turn the machines

off and pump him with morphine and his family fought for him,

so the doctors asked for a signal, and the man woke up, looked

at everyone, and then went back to sleep again. Before he died,

he woke again and said, "I found it. I found the key to life,"

and it sounded like nonsense, but it was this vision of the world

like the Zurich transit system and it was this fantastic, visionary

thing. And this is the work that is not happening in our communities.