Interrogating Drama

By Caridad Svich

The Pillowman

By Martin McDonagh

The Booth Theatre

222 W. 45th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

Martin McDonagh's The Pillowman

opens on the figure of a blindfolded man seated in a chair in

a nondescript interrogation room. After a silence, two detectives

enter. The familiar crime-genre scene of a detainee interrogated

by a good cop/bad cop team begins.

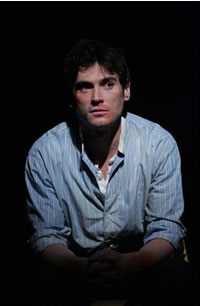

Information is doled out quickly. The detainee

is a mostly unpublished short story writer named Katurian (played

by Billy Crudup), who composes macabre fairy tales that are equal

parts Heinrich Hoffman and Stephen King. The low-level detectives

Tupolski and Ariel (played by Jeff Goldblum and Zeljko Ivanek)

work for a totalitarian dictatorship, and they have arrested Katurian

because his stories seem to have influenced three copycat murders

of young children. As the scene unfolds, we discover, as his screams

are heard from an adjoining room, that Katurian's slow-witted

brother Michal (played by Michael Stuhlbarg) has also been arrested.

The detectives cajole, taunt and terrorize Katurian in a witty

variation on familiar TV police drama.

In the twilit scene that follows, Katurian

tells the peculiar story of a young writer and his brother. Through

stylized peepshow re-enactments above and behind him, we witness

Katurian's parents decide to make their son into a successful

writer by subjecting him to the nightly screams of his older brother,

whom they torture repeatedly in extreme ways. When the child asks

about the screams, the parents deny them but encourage Katurian

to keep writing and use the strange "nightmares" to

fuel his imagination. When the young man finds out the truth,

he kills his parents and rescues his now brain-damaged older brother.

At this point the play shifts back to the

present, with Michal seated in a large prison cell listening to

Katurian's screams. The sadistic police are now torturing him.

The thread of violence, damage and abuse is what holds these brothers

together. Katurian is thrown into the cell with Michal, and they

confront the cycle of violent trauma that has destroyed their

lives. The piquantly disturbing irony is that this very cycle

has created Katurian's ability to spin haunting, if sensationalistic

stories, just as his parents had planned.

In this freewheeling, mostly legato scene

between the brothers--which particularly showcases Stuhlbarg's

affecting portrayal of Michal--McDonagh explores the alarmingly

suggestive power of literature and the psychological blur that

can occur between reality and fiction. The dark heart of the play

is contained in this scene, and if I don't divulge any more of

the plot, it's because the play depends in great part on the suspense

endemic to its thriller genre.

McDonagh's penchant for propping up his

plays by using the familiar frames of established genres is as

apparent here as it was in his acclaimed Leenane trilogy and The

Cripple of Inishmaan. Although The Pillowman starts

out as a tragically absurdist, self-aware policier reminiscent

of Kafka, it abandons itself to the more conventionally well-oiled

machinations of the thriller (emphasized by Paddy Cuneen's music

and Paul Arditti's sound design), even though the whodunit aspect

of the story is resolved relatively early on.

McDonagh and director John Crowley (who

also staged the play in its London premiere last season) set out

to expose the mechanisms of terror and desire that are intrinsic

to the genre, not only through the telling of Katurian's story

but also through the staging of some of his fictions throughout

the evening. Working expectations and reactions in cleverly astringent,

if sometimes overly indulgent, Tarantino-like maneuvers, McDonagh

and his talented artistic team toy with extreme comedy and violence

to arouse and discomfort their audience. While The Pillowman

is ostensibly about the power of literature and its inherent threat

to a censorious, dictatorial government, it is more about the

act of reading and viewing: how does a story affect us, and what

are the emotional triggers that draw us in in the first place?

McDonagh is a provocateur, and while there

is no denying his skill and guile as a dramatist working in a

popular form, there is something hollow at the heart of this play.

His chilly reserve is to be welcomed, and his strategies for laying

bare the erotica of violence, of sanctioned and unsanctioned sadomasochistic

pain and pleasure (echoes of Abu Ghraib), are effective. The play's

grander ambitions, however, which speak to key questions of how

societies are run and individuals are besieged by threats to their

imagination and free will, are less convincing. The prose style

and content of Katurian's stories, which are relayed often during

the evening as suggestive examples of twisted morality tales for

children (such as the Hoffman tales in Shockheaded Peter),

border constantly on the banal. The images of violence the stories

conjure are gruesome but not potent enough to resonate with any

profundity.

This may be indeed McDonagh's point: that

the stories we tell now in a media-saturated, violent world can

only be banal and lurid. But if we are to take his larger idea

seriously--that Katurian's stories are destined to outlive him,

that their power is too great to be dismissed--then the surface

banality of the stories is problematic. Trading in the language

of Grimm's fairy tales is not the same as reproducing their enduring

psychological weight and disturbance. Their primal element, and

the way they are embedded in our psyches almost like the myths

of ancient Greece, are not honored fully enough in McDonagh's

vision.

The cheapness of horror rather than its

essentially disruptive and liberating aspect seems to be what

McDonagh is after as a comment on our tawdry world. His emphasis

on telling the story through the eyes of trauma victims--as a

sort of confessional recovery--recalls the commonplace Jerry Springer-like

talk shows that have cheapened our national discourse, particularly

since 9/11. Unlike, for example, Sarah Kane's Blasted,

with which Pillowman shares major themes, McDonagh's

cathartic despair is intimated but never fully released. Although

he is extremely well served by his artistic collaborators (and

special mention must be made of Jeff Goldblum's razor-sharp wit

and Zeljko Ivanek's wiliness), as the evening unfolds the play

erases itself until we are left with the disconsolate image of

a fire burning: the Promethean fire of literature itself waiting

to be unleashed.