Injustice Is Served

By Terry Stoller

Guantanamo: 'Honor Bound to

Defend Freedom'

By Victoria Brittain and Gillian Slovo

New Ambassadors Theater (London)

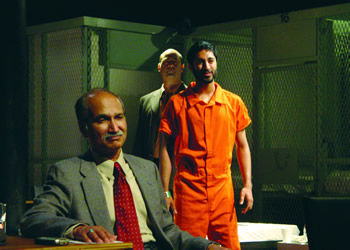

[Note: The London production of Guantanamo,

reviewed here, transferred from the Tricycle Theatre to the West

End in June 2004. A restaged production, with a new cast including

Kathleen Chalfant, opened on Aug. 26, 2004, at the Culture Project

in New York City, 45 Bleecker St. Box Office: 212-253-9983. The

photo above depicts the New York production.]

Since the mid-1990s, the Tricycle Theatre

in north London has demonstrated a commitment to documentary theatre.

In Britain, where the content of government inquiries has not

commonly been available to the public on television, the Tricycle

has taken up the mantle and staged edited versions of a number

of investigations. Artistic director Nicolas Kent, who believes

that "all art can significantly influence political and social

change,"* has presented tribunal plays on both international and

local issues.

In 1994 Half the Picture was a

re-enactment of sections of the Scott Inquiry into the sale of

arms to Iraq. The Colour of Justice (1999) uncovered

racism and negligence in the police investigation into the murder

of Stephen Lawrence, a young black man who was attacked by a gang

of white youths in south London in 1993. The play is based on

the transcripts of an inquiry launched five years after Lawrence's

murder, for which no one had been convicted. By 2003, weapons

and Iraq were again under discussion at a tribunal. The Tricycle's

Justifying War, done that year, is based on testimony

at the Hutton Inquiry into the circumstances surrounding the suicide

of British weapons expert David Kelly, whose name had been leaked

as a source for a BBC report that accused the government of exaggerating

Iraq's weapons capabilities as a rationale for waging war against

Iraq.

In January 2004, not waiting for a government

inquiry into the human-rights violations of the British detainees

who were sent to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the Tricycle commissioned

a play and began its own inquiry. Victoria Brittain, formerly

a journalist for The Guardian, and novelist Gillian Slovo

collected testimony from released detainees and their family members,

lawyers and human-rights workers. They supplemented the interviews

with correspondence from detainees, news conferences and lecture

material. The result is Guantanamo: 'Honor Bound to Defend

Freedom,' a chilling play whose subtitle is an ironic reference

to a sign to the prison camp.

Through verbatim accounts, the play relates

the circumstances of the detention of four men. Wahab and Bisher

al-Rawi, brothers whose family had emigrated from Iraq to Britain,

traveled to Gambia on a business venture to open a mobile peanut-oil

plant. Jamal al-Harith started out from Manchester to Pakistan

for a religious tour. Moazzam Begg went with his family from Birmingham

to Afghanistan in hopes of setting up a school there. Three Muslim

British citizens and a resident--all were picked up as terrorist

suspects. Wahab was released in Gambia after almost a month of

detention and interrogation. Bisher, Jamal and Moazzam wound up

at Guantánamo Bay. In the course of the play, we meet Ruhel Ahmed,

a young man from the Midlands who was also at Guantánamo, through

his letters home and testimony from his father. After more than

two years, Jamal al-Harith and Ruhel Ahmed were able to return

home. Moazzam Begg and Bisher al-Rawi, a voice-over announces

at the end of the play, are being held indefinitely at Guantánamo

Bay.

The accounts include unsubstantiated accusations,

guilt by association and being in the wrong place at the wrong

time. The al-Rawi brothers were detained and questioned by the

Gambian secret service and American officials about, among other

issues related to terrorism, their association with Islamic cleric

and alleged al-Qaeda leader Abu Qatada, a friend whose children

they had taken swimming. Wahab was eventually released, but his

property worth a quarter of a million dollars had "disappeared."

Bisher, an Iraqi citizen (when the family left Iraq they kept

the youngest son's citizenship in case there was a chance to recover

the property they had left behind), and Wahab's Jordanian business

partner wound up at Guantánamo.

Jamal's horror story began in October 2001

on a truck ride to Turkey, his new destination after he was warned

that the British might be unwelcome in Pakistan. The truck was

hijacked in Pakistan by Afghanis, and he was handed over to the

Taliban, who imprisoned him in Afghanistan, accusing him of being

part of a British special-forces military group. When America

bombed Afghanistan and the Taliban government fell, he was freed

but was soon transported by the Americans to a jail at a base

in Kandahar, interrogated about his life in England, and eventually

sent to Guantánamo.

Moazzam Begg's father tells the story of

"the best son of mine." Moazzam, who his father says always had

an altruistic nature, moved to Afghanistan because he wanted to

help the people there. He had difficulty obtaining approval from

the Taliban government to open a school, so instead he began to

install hand pumps for people who didn't live near a water source.

When America attacked Afghanistan, Moazzam took his family to

Pakistan, where he was arrested by Pakistani and American soldiers,

sent to Bagram air base outside Kabul, and later to Guantánamo.

After a year in custody, Moazzam wrote to his father: "After all

this time I still don't know what crime I am supposed to have

committed."

The traumas for the men pile up--endless

interrogations, censored and unsent correspondence, various methods

of being led around in chains, solitary confinements in a freezing,

bare metal cell, confessions made out of desperation. (In a stroke

of luck, Ruhel's confession to having been at an al-Farouq training

camp in 2000 was discredited, because, as MI5 discovered when

it checked the story for the U.S., he was working in a Currys

store in Birmingham at that time.) We hear testimony from lawyers

and human-rights activists who present powerful arguments on behalf

of the detainees, both on legal and humanitarian grounds. Lord

Justice Johan Steyn, in excerpts from a lecture that frames the

play, decries the U.S. practice of holding the detainees in the

military camp, thus putting them beyond the protection of any

courts. A brother of a Sept. 11 victim wonders why the American

government, with its abundance of resources to fight a war on

terrorism, hasn't used those resources in processing the detainees'

cases more quickly. When Donald Rumsfeld enters the scene, he

fends off questions at a news conference with imperious responses,

making distinctions between prisoners of war and unlawful combatants,

who, he claims, are not classified as prisoners but as detainees.

Indeed classifications became a strategy for skewing statistics

at Guantánamo: the number of suicide attempts dropped off when

they were reclassified by the military as Manipulative Self-Injurious

Behavior.

Much of the play is presented in direct

address to the audience, the character either standing or seated.

On a claustrophobic set, crowded with tables, chairs, cots, prison

cages, co-directors Nicolas Kent and Sacha Wares use spare staging

in which every movement counts. As detainees are said to be transferred

to Guantánamo, we watch them put on the requisite orange jumpsuits.

We see them exercise to keep in shape and stave off boredom. The

piece is punctuated with a call to prayers, announced over tinny

loudspeakers, and we see the detainees exercise one of the few

rights that hasn't been taken away from them: the right to pray.

It's through the practice of religious rites that we witness the

deterioration of Moazzam Begg. In an early letter home, Moazzam

writes from Bagram air base of having read the Koran almost seven

times and memorized many of its passages. Months later, he is

upset that he has nothing to do except read the Koran. At the

end of the play, now at Guantánamo, Moazzam, who has been chained

and held in solitary confinement, no longer responds to the call

for prayers. A final image is of Moazzam, beautifully acted by

Paul Bhattacharjee, seated on a cot, staring ahead blankly, while

those around him perform their devotions.

When I saw the play in London's West End,

I overheard a conversation during the intermission. An American

woman was informing her companions that Americans would not be

able to understand why the men had left England for such places

as Gambia, Pakistan, Afghanistan. Indeed my suspicions were aroused,

and I wondered why these men weren't trying to make a life for

themselves in Britain, why they didn't feel at home there. The

play offers a hint in Mr. Begg's story of his son's harassment

by the Birmingham police, who accused (then cleared) Moazzam of

having ties to the Taliban. But in fact the play is not trying

to prove the detainees' innocence or guilt. As Mr. Begg argues,

"Let the court decide whether he is guilty or not. If he is guilty

he should be punished. If he is not guilty he shouldn't be there

for a second." Guantanamo is about denying people due

process of law, about the violation of their human rights, about

the deterioration of democratic processes in the name of the war

on terrorism.

The power of this documentary drama lies

not just in actualities, in the heartbreaking stories, but also

in the presence of a group of actors who bring conviction and

humanity to the characters whose pain and outrage they embody.

Shaun Parkes, as Jamal al-Harith, movingly conveys Jamal's anger,

bitterness and hurt when he wonders why, if he's "scum of the

earth," he was ever set free.

The Guardian recently reported

that Ruhel Ahmed and two other men from Tipton (known in the press

as the Tipton Three) have made claims in a 115-page report about

abuses they suffered at Guantánamo Bay, some similar to those

inflicted on prisoners at Abu Ghraib that made headline news just

a few months ago. The Tipton Three say detainees still at Guantánamo

are deteriorating physically and mentally. Now that the U.S. presidential

campaign, the continued fighting in Iraq, and reports of terrorist

threats have overshadowed prison-abuse stories, at least in America,

the documentary play Guantanamo: 'Honor Bound to Defend Freedom'

is making a significant contribution by keeping the detainees'

stories very much alive.

*Quoted in Dave Calhoun, "Screen Test,"

Time Out London, July 7-14, 2004, 69.