Fruits of Anger

By J. Ellen Gainor

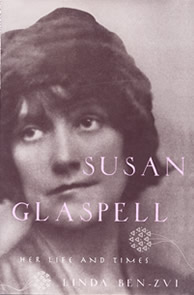

Susan Glaspell: Her Life and

Times

By Linda Ben-Zvi

Oxford University Press

448 pp., 29 halftones

$45

With what has by now become a familiar

trope in Susan Glaspell studies, Linda Ben-Zvi opens her new biography

of Glaspell on a note of anger: anger at an American literary

and theatrical tradition that had "disremembered" an important

woman writer; anger at the scholarship that had consistently devalued

Glaspell at the same time that it championed her male colleagues;

and even anger at herself for some unexamined, early collusion

in these practices. Ben-Zvi soon thereafter describes the epiphanic

moment when she began to question this tradition--when she started

to ask herself and others who this woman was and why there was

so little analysis of her life and work. Her quest for answers

has led her to produce a compelling and much-needed corrective

to this legacy of dismissal and neglect. Susan Glaspell: Her

Life and Times both complements the burgeoning field of Glaspell

studies and provides nuanced and fresh readings of Glaspell's

oeuvre. (Full disclosure: I am the author of the first full-length

study of Glaspell's dramaturgy and Ben-Zvi's co-editor on the

forthcoming Complete Plays of Susan Glaspell.)

For more than a quarter century, feminist

critics and others have endeavored to return Glaspell (1876-1948)

to the position of cultural prominence she held during her lifetime.

Over the years, the arc of Glaspell studies has quite neatly paralleled

the evolution of Anglo-American feminist criticism. In fact, Glaspell

became a subject of some of the discipline's most influential

early essays, including Annette Kolodny's "A Map for Rereading"

and Judith Fetterley's "Reading about Reading." From that first

stage of basic retrieval of lost women writers, through subsequent

more thorough critical engagements with texts and issues of authorial

identity and creativity (such as those connected with critical

race studies, ethnic studies, and LGBT studies), and, more recently,

in the arena of cultural studies and more integrated scholarship

that considers women writers as part of broader historical, geographic,

and economic contexts, Glaspell has been central. Ben-Zvi alludes

to each of these stages, passed through and folded into her almost-two-decades-long

process of research and composition, but wisely chooses not to

dwell on the troubling scholarly traditions and patriarchal pronouncements

prior Glaspell scholarship has had to overturn. Nevertheless,

Ben-Zvi understands that such dismissive critical traditions linger,

and that Glaspell's story may still be unfamiliar to many readers.

She thus builds on the more recent feminist critical foundation,

calculatedly treating Glaspell's validity as an influential figure

as a given and organizing the biography around her accomplishments.

Glaspell's many achievements include the

co-founding of the Provincetown Players. In the teens and early

twenties she was identified, along with Eugene O'Neill, as one

the country's leading dramatists. She was only the second woman,

after Zona Gale in 1921, to receive the Pulitzer Prize for drama

with Alison's House (1931). She was an award-winning

fiction writer, whose short story "A Jury of Her Peers" and its

dramatic counterpart, Trifles (1915/16), were immediately

identified as landmark texts. Her later novels appeared on best-seller

lists around the country. And in the 1930s, she served as the

Director of the Midwest Play Bureau for the Federal Theatre Project.

Given this catalogue of triumphs, Ben-Zvi unsurprisingly characterizes

Glaspell as a "pioneer," a woman who, throughout her life, challenged

assumptions of what women could or should do and repeatedly overcame

private and public obstacles to her creative and personal fulfillment.

Ben-Zvi sees a resonance between the progressive

era's influence on Glaspell and a number of the themes that pervade

her writing. First, Ben-Zvi perceives in Glaspell an overarching

desire to escape structures and to push boundaries--familial,

social, cultural, and artistic. In her personal life as well as

in her work, Glaspell sought to transcend convention; as she matured,

she actively resisted the conforming pressures of organized religion,

political conservatism, and other social norms. As a young woman,

for example, she stopped attending church with her family, and

instead chose to participate in the meetings of the Monist Society--an

organization that promoted discussions of socialism, Nietzschean

philosophy, evolutionary theory, and human sexuality, among other

advanced topics. At the same time, however, Glaspell strove to

understand traditions, especially those of her pioneer ancestors

who had settled in Davenport, Iowa. Her work reflects truthfully

and poignantly the pull many in her generation felt between their

love for and duty to family and its older values and their desire

to embrace this new, progressive ideology for themselves and the

nation.

In the first third of the biography, Ben-Zvi

details the key departures from the traditional midwestern woman's

life that Glaspell's story epitomizes: college education at Drake

University and graduate course work at the University of Chicago;

an early stint as a society columnist for the local Davenport

newspaper, the Weekly Outlook, and a first full-time

post after graduation as a court and state house reporter for

the Des Moines Daily News; a decision soon thereafter

to commit to a full-time creative writing career, which brought

Glaspell early and consistent success nationally and internationally;

travels in Europe and residence in the bohemian Latin Quarter

in Paris; and a relationship with a married man, George Cram ("Jig")

Cook, who became her husband in 1913 following his divorce from

his second wife. In narrating these events, Ben-Zvi establishes

both a foundational feminist understanding of Glaspell's life

and work and an essential comparative framework through which

her readers can understand the groundbreaking nature of Glaspell's

choices.

Ben-Zvi, for example, juxtaposes Glaspell

with the Davenport doyenne of "local color" fiction, Alice French

(a.k.a. Octave Thanet), whose stories and novels championed the

older, conservative values of the region. And Ben-Zvi also compares

Glaspell with another Iowa contemporary, Hamlin Garland, whose

writings reflected an equally polarizing idealization of poverty

and labor. Ben-Zvi highlights the important distinctions among

these three authors to reveal the complexities in style, characterization,

and content of Glaspell's work. Ben-Zvi establishes the basis

for considering Glaspell among the emerging American modernists--artists

committed to the truthful (but not necessarily realistic) representation

of social and political issues, to an honest exploration of national

culture and identity, and to experimentation with the forms and

styles that could best convey these concerns. Moreover, Ben-Zvi

links Glaspell's formative years in Iowa with an immersion in

American culture (especially the writings of Emerson) and early

introduction to the "Chicago style" of journalism and fiction.

Ben-Zvi similarly sees Glaspell's sojourn in Paris and exposure

to Maeterlinck as instrumental to her later emergence as a dramatist.

One of the problems facing any Glaspell

biographer is the comparatively modest amount of genuinely self-revelatory

information she left behind. As Ben-Zvi and others have noted

(most pertinently, Glaspell's previous biographers, Marcia Noe

and Barbara Ozieblo), Glaspell did not keep lengthy journals or

diaries, and although she retained letters received from friends,

lovers, and colleagues, her correspondents generally did not keep

hers. Like other Glaspell scholars, then, Ben-Zvi has relied heavily

on The Road to the Temple (Glaspell's biography of Cook,

who died unexpectedly in Greece in 1924) for background details

of their relationship and entwined careers. Ben-Zvi has also recently

published a new edition of this work and has argued persuasively

for its importance as a key text in Glaspell's oeuvre--not only

as a biography of Cook but also a source of critical insights

on their common midwestern backgrounds, on American arts, politics,

and culture, and on issues of gender, class, and national identity

in the early twentieth century. Ben-Zvi combed all the relevant

archives--in Iowa, New York City, Cape Cod, and elsewhere--for

material to confirm the accuracy of, and to fill the gaps in,

Glaspell's narrative. As an O'Neill scholar, Ben-Zvi already had

a formidable background in much of the theater history and dramatic

criticism of the period, which she augmented with readings of

autobiographies, critical studies, and history of the era to provide

a fuller and more balanced account of individuals and events.

The memoirs of Mabel Dodge and Floyd Dell, for example, presented

Ben-Zvi with vivid images of Greenwich Village and Provincetown

life from which she could draw. In deploying these sources, Ben-Zvi

provides some important correctives to both earlier Glaspell studies

and other works on the period, especially those that took The

Road to the Temple as comprehensive and factual. (Glaspell

slighted the early phases of her relationship with Cook and glossed

over his writer's block, alcoholism, and adultery.) For scholars

familiar with these figures and their era, there may be some disappointment

that Ben-Zvi did not discover a hidden trove of new information,

but for the general reader her book offers an accessible and engaging

entrée to their world.

Because the story of Glaspell--especially

her work in the theater--is so intertwined with that of Cook,

Ben-Zvi's biography can be read as both homage to and critique

of Robert K. Sarlós's groundbreaking study Jig Cook and the

Provincetown Players (1982). The works cover similar ground,

but Ben-Zvi provides new and distinct perspectives on the individuals

and events connected with the legendary company. She represents

more fully the interconnected lives and careers of many of the

Players, as well as their ties to leftist politics and feminism.

Equally important, she adjusts the historical record to foreground

the significant contributions of Glaspell and other women to the

success of the Players (a topic also explored in Cheryl Black's

The Women of Provincetown 1915-1922). Ben-Zvi, along

with other Glaspell scholars, also offers important correctives

and supplements to O'Neill studies by demonstrating conclusively

his indebtedness to both Glaspell's innovative experiments in

expressionist dramaturgy and her editorial expertise as an early

reader of his work. These observations strongly challenge assumptions

that Glaspell must have imitated O'Neill and that O'Neill's was

a solitary creative process. They enrich and diversify our understanding

of early 20th-century American theater history, previously focused

so heavily on this one male playwright.

Glaspell's work as a dramatist and Ben-Zvi's

discussion of her plays, understandably, occupy the center of

the biography. Because Glaspell's playwriting lies at the chronological

mid-point of her career and has been perceived as her more adventurous

work stylistically and topically, Ben-Zvi devotes a full third

of the biography to the brief but exciting period of 1914-1922.

This section covers the founding of the Provincetown Players and

the composition of Glaspell's eleven plays produced by the group.

It closes with the couple's departure for Greece, which turns

out to be the end of their affiliation with the company and of

its role as the leading developer of modernist American theater.

In this section especially, Ben-Zvi's commitment to enhancing

our knowledge of Glaspell and her writing merits note; even for

a text so over-examined as Trifles she provides new insights

and fresh readings. In discussing this canonical piece, based

on a murder case Glaspell covered in 1900-01 as a young reporter,

Ben-Zvi reminds us of the impact the fifteen intervening years

would have had on the author. She reads the play through Glaspell's

lived experience as a woman in U.S. culture since the turn of

the century, calling attention to the suffrage movement and changing

attitudes toward women's roles in public and private spheres and

thus explicating the historical and critical contexts of Glaspell's

characters, dialogue, and plot.

Because Glaspell's early fiction and dramaturgy,

the relationship of Glaspell and Cook, and the story of the Players

have received comparatively more critical attention, the last

third of Ben-Zvi's biography may prove the most revelatory, even

for readers familiar with the general arc of Glaspell's life and

career. While some scholars posit a decline in Glaspell's importance

and innovation as a writer following Cook's death, Ben-Zvi argues

convincingly for a thorough re-consideration of this period of

Glaspell's career, which includes the composition of not only

her Pulitzer Prize-winning drama, Alison's House, but

also her most commercially successful novels (which are discussed

at greater length in Martha Carpentier's The Major Novels

of Susan Glaspell). Precisely because of the dismissal and

neglect of Glaspell's later writing (especially Alison's House,

which the New York critics reviled when it received the Pulitzer),

Ben-Zvi's thoughtful discussion of these works and the circumstances

of their composition allows for a much fuller understanding of

the final phase of Glaspell's creativity.

Ben-Zvi also covers in detail here Glaspell's

relationships with two considerably younger men, Norman Matson

and Langston Moffett--unconventional intimacies for the time,

even within her circle. Clearly, these later affairs had nowhere

near the impact on her work that her friendship and marriage with

Cook did (Ben-Zvi believes that Glaspell's is the dominant voice

in The Comic Artist, co-written with Matson). Yet they

do demonstrate Glaspell's continued resistance to social conventions

in matters of love. (Glaspell hinted that, for the sake of her

family, and perhaps also to safeguard her publishing career, she

let others assume she and Matson had wed.) The biography also

frankly discusses Glaspell's struggles with alcohol and depression;

unlike Glaspell's almost hagiographic portrait of Cook, Ben-Zvi

balances her admiration for Glaspell with the necessary objectivity

to present the life and work truthfully and fairly.

Ben-Zvi's deep engagement with Glaspell's

texts, career, friendships, loves, and beliefs complements her

portrait of a woman experiencing some of the most eventful periods

of recent U.S. history. These include two world wars and the progressive

era, with its transition from agrarian to industrial society and

its accompanying changes in the lives of women and families, as

well as the crash, the great depression, and the New Deal's promise

of renewed economic stability for all. History has taught us about

all these events from certain well-established perspectives, but

Ben-Zvi's biography offers glimpses of these moments as points

of intersection with the life of a woman artist, refracted also

through her fiction and drama. Glaspell's writing thus emerges

as history as well--chronicles of life in the conservative American

heartland, in the bohemian communities of Greenwich Village and

Provincetown, and in a post-war nation grappling with competing

ideologies for its future.