Exclamation Point

By Kevin Byrne

Chautauqua!

Created by the National Theatre of the United States of America

Written by James P. Stanley and Normandy Raven Sherwood

P.S. 122

(closed)

Chautauqua tried to create an ideal America

and Chautauqua! tried to create an ideal Chautauqua;

both were impossible projects.

The National Theatre of the United States

of America (NTUSA) has made failure an integral part of their

dramaturgy for the past several productions. Their 2006 Abacus

Black Strikes NOW!: The Rampant Justice of Abacus Black looked

at the compromises people make for the sake of security and their

2008 production of Molière's Don Juan highlighted the

changeable nature of even very pious people when faced with base

stimuli. Human fallibility has always been celebrated in their

shows, and for the company an equally human phenomenon is the

construction of idealized concepts that cannot really be reached.

Their past work has been inspired by various

performance styles from self-help seminars to game shows, but

with the Chautauqua form they seem to have found a perfect reflection

of their aesthetic mission. The Chautauqua tent show was a variety

entertainment that toured the rural United States throughout the

late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, spreading knowledge

and nationalism. Its intent was to create stalwart, religious

Americans, and it carried its contradictions within itself. The

truths Chautauqua! holds to be self-evident are that

the United States is in reality a country obsessed with violence,

profit, and the pursuit of entertainment. NTUSA had only to amplify

some of the Chautauqua's internalized tensions to expose this

national enterprise. But more than just satirizing Chautauquas

and the audiences that made them popular, the show was an elegy

to a performance style it is no longer possible to present or

watch without a large helping of irony and a small dollop of melancholy.

Chautauqua provided both the form and content

of Chautauqua! It hewed to the tent shows' choppy vaudeville

format while at the same time describing and performing the decline

of their popularity. The performance included historical and philosophical

lectures, a reenactment of a famous duel, numerous songs, a handful

of dances, a puppet show/nature lecture, and random tidbits of

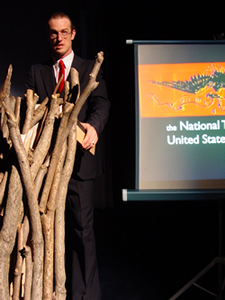

local knowledge. It began with the introduction of Master of Ceremonies Dick Pricey

(company member James P. Stanley), last seen introducing NTUSA's

Don Juan. Pricey was lecturer, curator, and commentator,

and his stuffy demeanor and stentorian tones recalled the traditional

Chautauqua personnel--his reactions to the more bizarre antics

of the other performers and his sometimes successful attempts

at keeping a lid on the proceedings continually reaffirmed the

distance between the contemporary audience's sensibilities and

those of their Chautauqua forbearers. Stanley brought an uncomfortable

earnestness to his role as professional scold, like a school dance

chaperone whose job is to police the punch bowl.

It began with the introduction of Master of Ceremonies Dick Pricey

(company member James P. Stanley), last seen introducing NTUSA's

Don Juan. Pricey was lecturer, curator, and commentator,

and his stuffy demeanor and stentorian tones recalled the traditional

Chautauqua personnel--his reactions to the more bizarre antics

of the other performers and his sometimes successful attempts

at keeping a lid on the proceedings continually reaffirmed the

distance between the contemporary audience's sensibilities and

those of their Chautauqua forbearers. Stanley brought an uncomfortable

earnestness to his role as professional scold, like a school dance

chaperone whose job is to police the punch bowl.

The bulk of the piece was devoted to Chautauqua-style

edutainment vignettes that barely hid a violent or exploitative

core underneath a genteel exterior. The humor of these scenes,

and they were very funny, was an interrelated mix of two comedic

tensions: the amateurishness of the presentation contrasted with

the dead seriousness of the presenters and the lofty aims of the

lectures concealing the compromising, messy humanity actually

on display.

An early lecture titled "Why I Like Maps"

was an overview of European cartography from the Renaissance to

the present that defended earlier maps full of speculation and

wonderment, preferring them over newer, scientifically calibrated

ones. One needn't be a hard-core Foucaultian to notice that in

decrying the mathematical maps, created to show trade routes,

the lecture was championing the individual discoverer over state-sponsored

and money-driven institutions.

The nature lecture "In the Mud" exposed

the eat-and-be-eaten processes in the chain of life from single-celled

organisms all the way up to marauding Cossacks (by way of larvae,

frog, bird, fox, bear, and vulture). This chain was dramatized

by colorful puppets and masks, and the lack of blood or dismemberment

did little to hide the Hobbesian bent of the thesis.

Another performance-within-a-performance

was a reenactment of the duel between Aaron Burr and Alexander

Hamilton that led to the latter's death. It was a piece of history,

of Americana, and of theatre, yet the drama and tension were undercut

by long digressions in which the actor playing Hamilton stepped

out of the scene to explain the niceties of dueling and the killing

power of eighteenth-century pistols. In all these examples, greed

was presented as triumphant and death as an unfair certainty,

even as the lecturer tried to convince us that the world was otherwise.

Dick Pricey delivered a eulogy to the Chautauqua

form as the performance drew to a close. Mass culture was certainly

the villain of the piece, or rather its fated tragic outcome.

The course of history drove the Chautauqua toward its own obsolescence

as its repressed salaciousness was displayed cheaper, faster,

and louder through its technologically distributed offspring.

To illustrate this, the shallow stage that

had housed the earlier lectures opened to reveal a large space

replete with black-leotarded dancers executing Merce Cunningham-esque

movements with mock solemnity--a humorous, if obvious, way of

sending up the pretensions of modern dance. The stage was then

flooded with dancers in multi-colored outfits while the music

and choreography changed to pure Flashdance. The saccharine

sweetness and forced jocularity of the scene went from goofy to

grating. I'm not sure if this was intentional, but the company

demonstrated its affinity for the old-fashioned Chautauquas by

choosing a truly obnoxious idiom for its representation of mass

culture.

The

final tableau of Chautauqua! was a fantastic vision that

managed to be bizarre and also tender. The dancing morphed into

a leg show, and a very literal one at that: a surreal kick-line

of bare legs with upper torsos hidden beneath clever costume contraptions.

The flash-dancers lined up along the back wall, supporting the

letters of a huge blinking sign: CHAUTAUQUA! And then Dick Pricey,

defender of all things Chautauqua, began undressing with the same

awkward earnestness that characterized his other duties as emcee.

It was, he said, an act of love. We, the people, demanded this

of him. Stripped bare by his audience, Pricey confessed, "Now

may be the best time to tell you, we were paid to be here tonight."

He explained that an influential backer of the show forced the

company to add the more prurient spectacles and also forced them

to punctuate the show's title with an exclamation point. They

didn't want to do it, but, times being what they are…

The

final tableau of Chautauqua! was a fantastic vision that

managed to be bizarre and also tender. The dancing morphed into

a leg show, and a very literal one at that: a surreal kick-line

of bare legs with upper torsos hidden beneath clever costume contraptions.

The flash-dancers lined up along the back wall, supporting the

letters of a huge blinking sign: CHAUTAUQUA! And then Dick Pricey,

defender of all things Chautauqua, began undressing with the same

awkward earnestness that characterized his other duties as emcee.

It was, he said, an act of love. We, the people, demanded this

of him. Stripped bare by his audience, Pricey confessed, "Now

may be the best time to tell you, we were paid to be here tonight."

He explained that an influential backer of the show forced the

company to add the more prurient spectacles and also forced them

to punctuate the show's title with an exclamation point. They

didn't want to do it, but, times being what they are…

The play had little plot to speak of, other

than presenting a nostalgic vision of a bygone America that the

show itself kept undercutting. It was as sophisticated and pointed

as NTUSA's previous endeavors, and also more moving and sentimental.

This company has always found inspiration for their shows in various

entertainment genres. With Chautauqua! they found moments

of quiet sadness within the manic parody.