HotReview.org Editor's

Picks

Shows Worth Seeing:

The Pavilion

By Craig Wright

Rattlestick Playwrights Theater

224 Waverly Pl.

Box office: (212) 868-4444

Craig Wright’s The Pavilion was written

in 2000 but has taken 5 years to reach New York, despite being

nominated for the Pulitzer Prize and receiving numerous regional

productions. The ubiquitous speculation about this delay has ranged

from the dismal post-9/11 Off-Broadway economics to a longstanding

urbane prejudice against anything that smacks of the old-fashioned

wholesomeness of Thornton Wilder. Wright’s sweet, thoughtful

work indeed owes a lot to Wilder, yet its originality, its prickly

contemporaneity, and its strong, blessedly unfashionable sincerity

are also beyond question. The nominal setting is a 20-year high-school

reunion in Minnesota, where Kari (Tasha Lawrence) sees Peter (Brian

D’Arcy James) for the first time since he ran off, leaving

her pregnant and heartbroken. Both have been through a lot in

the meantime, and are unhappy, and as the evening progresses they

move slowly through swamps of rage and regret to consider renewing

their relationship. It’s no ordinary evening and no ordinary

setting, though, as the entire action is presided over by a Narrator

(Stephen Bogardus) who editorializes and imposes himself even

more determinedly than his obvious forebear, the Stage Manager

in Our Town. This Narrator transforms a humble tale of

loss and regret into a remarkable meditation on time, waxing poetic

(and a little prolix, at times) about such recondite matters as

forgiveness and spiritual presence. The net of cosmic connections

he posits doesn’t quite hold together in the end, but there’s

more than enough lucid emotional truth in this work—and

in these excellent performances—to leave most open-minded

viewers happy they went.

-------------------------------

The Girl in the Flammable Skirt

Adapted by Bridgette Dunlap from the book by Aimee Bender

Walkerspace

46 Walker St.

Box office: (212) 868-4444

Aimee Bender’s stories are written in a bold

and crisp magical realism that surprises by consistently finding

fresh treasures in self-consciously bizarre waters that one would’ve

thought others had thoroughly fished out. The fable-like tales

in the 1999 collection The Girl in the Flammable Skirt

veer off into unpredictably weird and violent currents, tempered

by a subtly aggressive undertone that keeps them from ever turning

sappy even though they’re essentially about very conventional

matters such as teenage loneliness and suppressed passion. A young

woman comes home one day to find her lover stuck in a process

of “reverse evolution,” losing “a million years

a day”: first he’s an ape, then a sea turtle, eventually

a one-celled creature she releases into the sea. A mermaid uses

crutches and an imp uses stilts to try to fit in as normal high-school

students. A girl with a hand of ice and another with a hand of

fire become different sorts of misfits and healers in a creepily

isolated provincial town. The wisdom of adapting Bender’s

stories into drama isn’t obvious: an imagined “fire

hand,” for instance, is always going to be more astonishing

than any live effect with a glove. No doubt partly because of

the terrific female protagonists, however, the Ateh Theater Group—a

collective of seven women—has chosen this material for its

inaugural production, and the show is well worth seeing. Director

and adaptor Bridgette Dunlap has fine sense of pacing and tone

and a knack for knockabout comedy. Also, the young company ultimately

makes up in pep for what is lost in marvelousness, so that their

enthusiasm and cleverness come off in the end as a sort of surrogate

marvelousness that does Bender proud.

----------------------

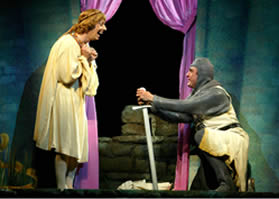

Spamalot

By Eric Idle and John Du Prez

Shubert Theatre

225 W. 44th St.

Box office: (212)239-6200

The great surprise of this musical recycling of

the classic movie comedy Monty Python and the Holy Grail

is the amount of pleasure that can evidently be had at a Broadway

show almost completely devoid of surprises. The play is not so

much written as cobbled together from gags and vignettes so familiar

to the audience that laughs often occur before a joke is told.

The very appearance of certain beloved faux-medieval costumes,

props and set pieces is enough to create giggling spasms at some

points. There are scraps of novelty: the addition of silly songs

and Vegas razzle-dazzle, as well as the transformation of self-consciousness

about film into self-consciousness about theater (the toothsome

Sara Ramirez, as the Lady of the Lake, has some wonderfully gratuitous

numbers). The show is basically a masterful spectacle of repackaging,

though. And what’s interesting about that is that the audience

is laughing at the old gags for new reasons. People seem to savor

the experience of enjoying the jokes in the particular circumstance

of the theater, perhaps because that communal context recalls

the original post-screening group-guffaws that extended their

first enjoyment of the movie for months and years afterward. Quasi-private

ribbing is reinvented and validated as a public event. In any

case, the palpable thrill of rediscovery has a college-reunion

flavor that is undeniably infectious.

-------------------------------

Doubt

By John Patrick Shanley

Walter Kerr Theatre

219 W. 48th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

This splendidly acted, 90-minute clenched fist of a play may

be the most penetrating and tautly written work of Shanley’s

long career. It’s certainly the most urgent. Cherry Jones

plays a tight-lipped, straight-laced, rule-mongering nun who,

as principal of a Bronx Catholic school in 1964, suspects the

young parish priest of misbehaving with an 8th-grade boy. She

has no hard evidence but nevertheless feels certain and is determined

to bring the priest down. Father Flynn is clever, earnest, liberal

and likeable, though, and the actor Brian F. O’Byrne gives

him a fascinatingly ambiguous edge of intellectual ambitiousness.

By the time he finishes defending himself the audience doesn’t

know whom to believe. Jones’s severity as Sister Aloysius

is frightening and her authoritarian harangues about self-effacement

in teaching to Sister James (Heather Goldenhersh), the boy’s

teacher, make her hateful, but as she presses the question of

the kid’s immediate safety--in the context of a rigid, top-down

institutional structure that won't protect him--the plot starts

to work as a powerful parable of justice and pseudo-justice in

a time of supposed emergency. Director Doug Hughes has found just

the right pace for the action, keeping it tightly coiled until

about two-thirds through when open confrontation replaces speculation

and insinuation. It’s thrilling to watch these formidable

actors run with the ball after that point, particularly when you

can really see their faces. Anyone who can afford it should spring

for the front seats in the big Broadway theater where the show

has now moved; the nature of the stalemate between this nun and

priest can't be fully appreciated without seeing the subtlety

of O'Byrne's reactions during the penultimate scene.

------------------------