HotReview.org Editor's

Picks

Shows Worth Seeing:

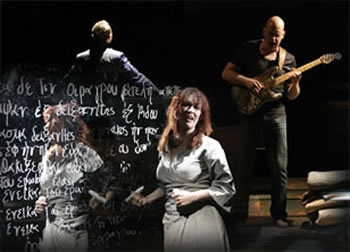

Orpheus X

By Rinde Eckert

The Duke on 42nd St.

229 W. 42nd St.

Box office: (646) 223-3010

The mythical Orpheus was undone by a moment

of desperate doubt. A musician so skilled he could move rocks

and trees with his lyre, he convinced the rulers of the underworld

to release his beloved Eurydice but lost her again by looking

over his shoulder. In Orpheus X, the writer, composer

and performer Rinde Eckert (whose musicalized Moby Dick

adaptation in 2000, And God Created Great Whales, was

extraordinary) reimagines this heartbreaking tale as a mini-opera

about the obsessions and chronic self-doubts of a famous rock

star. The meteoric career of Eckert’s Orpheus comes to a

standstill after a taxi he is riding in accidentally kills a beautiful

poet named Eurydice. He then reads her poetry and comes to know

and envy her as an artist courageous enough to face questions

of emptiness he had always avoided. Meanwhile, Eurydice adjusts

to the underworld, where all writing is done in chalk, easing

the process of forgetting. What is the meaning of a rescue attempt

in this circumstance? What good, and whose interest, does it serve?

In this piece, Eckert has graduated from the quiet duo cast with

piano in And God Created Great Whales to a trio cast

with a crackling four-piece jazz-rock band. He performs here with

the marvelous singers Suzan Hanson and John Kelly. Directed by

Robert Woodruff, he has also incorporated video, collaborating

with videographer Denise Marika and set designer David Zinn to

create a fantastically spooky and resonant environment that never

lets the eye rest. This is a place where coming to terms with

mortality and finding enduring reasons to make art seem self-evidently

like twin obsessions--two sides of the same creative coin. The

show is also unforgettably sensuous (Hanson, for instance, furiously

writes on the floor with chalk, in the nude, beneath the bleachers

as the audience enters). It's also powerfully haunting, not least

because the music alternates between heartbreakingly simple melody

and grating dissonance.

--------------------------------------

Idiot Savant

By Richard Foreman

The Public Theater

425 Lafayette St.

Box office: (212) 539-8500

For several years Richard Foreman has been

trying to incorporate film and video into his theater works, with

rather spotty and frustrating results. The biggest problem, in

my view, has been that while his theater always drew its life-breath

from an intense engagement with present-tense moments, perpetually

refreshed and reinvigorated by his fragmented texts and enigmatic

staging techniques, film and video could never replicate that

experience because they were always showing past events. The superimposed

media passages could never be risky or unpredictable like the

live theatrical action; worse yet, they were inherently competitive

with it. They had the effect of draining energy from the live

action, making it seem slow and anemic, and one left the productions

wondering why Foreman didn’t just make a film.

In his latest work Idiot

Savant, he has wisely returned to his core strength: theater

that trades on the perpetual surprise of each and every newly

arriving moment. The show’s text is ostentatiously resistant

to story and character development, as always. The stage is outfitted,

as usual, as a cluttered art installation, with Hebrew letters,

strings, and fetishized bric-a-brac everywhere. What’s new

this time is a certain air of compromise with conventional theater

in that the actors now often do what they say: e.g. hold out a

gift-wrapped box when referring to one, or attempt to kiss when

speaking of kissing. This literalism makes the action seem more

accessible even when it isn’t. The show’s pace is

also slower and more deliberate than in the past, as if Foreman

had made a pointed effort to meet his larger audience in the middle

(the show is performed at the Public rather than at Foreman’s

own tiny space), only to demonstrate that this middle is every

bit as bewildering as the extremes they may have feared. There

is a certain confident savoir faire in the air here, emanating

no doubt partly from the star actor in the leading role: Willem

Dafoe.

Foreman’s recorded

voice warns the performers near the beginning that they shouldn’t

try to steer the action toward any particular purpose but rather

allow it to remain a series of obscure and ambiguously related

moments. Dafoe enacts the central consciousness charged with upholding

this doctrine of resistance to Aristotelian drama—a role

(if we can call it that) that he plays with marvelous, nonplussed

savoir-faire. Foreman teases him (and us) with various allurements

from the dramatic model we supposedly hunger for, such as a sudden

desire at one point to appear not in Idiot Savant but

rather in a different play called Arrogant Fool (presumably

akin to Oedipus Rex), but he bumbles on to fulfill his

Foremanian anti-destiny with Mister Magoo aplomb. The etymological

root of the word “idiot” is the Greek “idiotes,”

meaning a private person lacking particular skills and hence any

meaningful relationship to the social group. Foreman’s “idiot”

refuses what is the traditional lead actor’s relationship

to his public, based on ingratiation and servility, offering instead

a reinvigorated concept of the social group based on our mutual

enjoyment of present-tense moments. In such a utopian world, everyone

is a “savant.”

---------------------------------

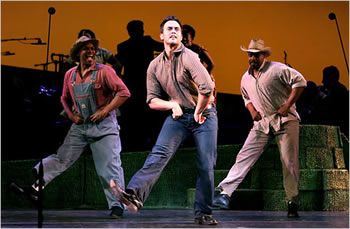

Fela!

By Jim Lewis and Bill T. Jones

Eugene O'Neill Theater

230 W. 49th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

Before Fela!, Bill

T. Jones’ and Jim Lewis’ musical about the career

of the Nigerian song-writer and performer Fela Anikulapo-Kuti

(1938-1997), my high standard for sheer dancing energy in a Broadway

show was In the Heights, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s salsa-packed

musical-explosion about love and loyalty in an unsung Manhattan

neighborhood. Astonishing as it may be, the first hour of Fela!

is actually more percussion-pumped and ice-water-in-the-face bracing

than Miranda’s show. It also tries to evoke a very specific

place. Fela!’s producers have decorated the interior

of the Eugene O’Neill Theatre like the Shrine nightclub

in Lagos where Fela made musical and political history by developing

a form of rebellious music known as Afrobeat, combining his songs

with seditious talk from the stage, and refusing to leave the

country even when threatened, arrested and beaten by the authorities.

There are works of African art, political posters and news clips

from the 1960s and 70s on nearly every surface, and some seats

have been removed to allow performers to dance and frolic in the

aisles.

In this happy and upbeat environment,

the show begins with an infectious, pelvic-gyrating number illustrating

the tremendous appeal and tenacious hold of Afrobeat, and it doesn’t

let up until intermission. The electric dynamism running through

the lead actor (I saw Kevin Mambo, who alternates with Sahr Ngaujah),

as well as the seductively undulating chorus of female dancers

and the crack jazz-rock band, makes the political threat that

this music posed to Nigeria’s dictatorial regime clear and

palpable. That is a remarkable achievement when you think it over:

Jones and Lewis have done (at least for an hour) what no rock

musical since the original Hair (NOT the recent revival)

has managed to do: communicate viscerally how music itself may

be truly political dangerous under certain social conditions.

The problem is that, after this dynamite opening, the show unfortunately

has nowhere to go. It can’t tell a sophisticated or complex

biographical story while keeping its music and dancers constantly

pumping, and the percussion alone isn’t enough to sustain

interest for 2 hours and 40 minutes. The show’s book, mostly

stuffed into extremely brief remarks between songs, soon gets

bogged down in very sketchy political slogans and romantic bromides,

and the evening seems to limp to a finish despite its non-stop

energy. The first half of Fela! is well worth it, however.

You’ll learn much that you didn’t know, and you won’t

soon forget those swinging pelvises.

------------------------------------

Finian's Rainbow

By Burton Lane, Yip harburg and Fred Saidy

The St. James Theatre

246 W. 44th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

Finian’s Rainbow is a charming,

feel-good artifact from 1947 that turns out to have a few pointed

political barbs for 2009. A fanciful, often preposterous tale

about people who bury leprechaun gold in the emblematic southern

state of Missitucky, it offers a loopy version of the same refreshingly

exuberant post-war optimism that made Oklahoma such a

landmark in musical history. The key difference between the two

shows is that Finian’s Rainbow confronts several

serious potential obstacles to the putative golden future of the

nation: namely, greed and racism. The Irish immigrant Finian brings

stolen leprechaun gold across the ocean because he’s convinced

that burying it near Fort Knox will make it grow. It doesn’t

literally grow, but it does instill hopefulness in the local populace—a

feeling that’s presented as a moral obligation. Interestingly,

one of the show’s key songs is about the virtue of buying

on credit. The audience laughs heartily at that, most of them

no doubt oblivious to the fact that the play is in part laughing

at them. The message, I suppose, is that people have to trust

one another; that’s what makes our country and our capitalist

system great. Yet it’s also made clear that the future is

only as secure as the next outsize order for the tobacco the sharecroppers

break their backs to harvest. In any case, the best humor in the

play isn’t about greed but rather intolerance. The satirical

sequence where a racist U.S. Senator is turned temporarily black

by leprechaun magic will never grow old. The play also quietly

mocks the no-brain optimism of the star couple’s happily-ever-after

marriage with a subplot marriage between a lonely mute girl and

a roving-eye leprechaun who admits he just wants to “love

the girl I’m near.” This revival directed and choreographed

by Warren Carlyle is solidly cast and infused with just the sort

of wit-inflected earnestness the material needs. (Any whiff of

South Park cynicism would kill it.) The producers also

deserve credit for recognizing the affinities of such old and

comparatively simple material with our complicated current moment.