HotReview.org Editor's

Picks

Shows Worth Seeing:

Speed-the-Plow

By David Mamet

Ethel Barrymore Theatre

243 W. 47th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

Once in a while, an actor—invariably

male—locates the music within David Mamet’s bullying

staccato language with such deep and intense sympathy that he

ends up suffusing the play with magnificent light, even though

everything he says is disgusting. This happened several times

with Joe Mantegna in the 1980s (in Glengarry Glen Ross

and Speed-the-Plow), and it’s happening now in

Neil Pepe’s superb revival of Speed-the-Plow. I

refer not to the HBO headliner Jeremy Piven who is fine as Hollywood

producer Bobby Gould (the role originated by Mantegna) but rather

to the amazing stage actor opposite him, Raul Esparza. Esparza

pumps up the role of Charlie Fox, Gould’s less powerful

associate, with such absurdly supercharged aggression that his

cynical quips drop like philosophical pearls, and his manic movements

become the stuff of a sort of amazing and hilarious dance. He

leaves you breathless, not only because of his energy but because

there isn’t a false note in the whole manic race he runs

for 85minutes. Pepe was also shrewd to cast Elisabeth Moss (from

Mad Men) as Karen, the office temp who almost ruins the

boys’ blockbuster movie deal by injecting a dose of sincerity

along with the sex requested of her. Because Moss is a bit older

and less bimboesque than the typical Karen, the audience can take

her somewhat more seriously than they otherwise would, and that

makes her threat more substantial. Speed-the-Plow is

not a think piece. It’s more like the dramatic equivalent

of one of those G-force simulators they use to train astronauts,

and if you enjoy that sort of exhilarating flattening, this is

the show for you.

-------------------------------

Billy Elliot: the Musical

Directed by Stephen Daldry, Book and lyrics by Lee Hall, Music

by Elton John

Imperial Theatre

249 W. 45th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

Curiously enough, this eagerly

awaited musical adaptation of the movie Billy Elliot

is almost as good as its hype. The story about a boy from a gritty

northern English coal-mining town who discovers a passion for

ballet was always irresistibly charming—just the sort of

triumph-against-the-odds, home-town-boy fairytale Hollywood got

rich on. The British adaptors of this show have been unusually

clever, though, in giving the tale strong theatrical legs. Elton

John’s rousing anthems and ballads pull all the right heartstrings

to make the audience cheer for both the boy’s success and

the victory of the union in the 1980s miners’ strike that

forms the play’s social background. But since that strike

ultimately failed—the Thatcher government famously broke

the union—the play’s impassioned cries of “solidarity”

have decidedly funereal overtones, and the story of the boy’s

individual triumph has particular poignancy against the bitter

failure of his loved ones’ collective action. This incongruity

gives the work a modest political complexity that other Cinderella

stories lack. The show is also wonderfully inventive. Director

Stephen Daldry (who also directed the movie) has inserted bizarrely

fluid choruses of cops and miners, for instance, who spread their

good and bad energy willy-nilly while sweeping through windows,

gyms and kitchens. At one point, Billy dances a strangely anomalous

pas de deux with his imagined older self, who seems to

provide the only viable adult role model he can muster. There

are half a dozen inspired creations of this kind, as well as superb

performances by (among others): Haydn Gwynne, who finds just the

right mixture of stoniness and congealed syrup for Billy’s

dance teacher; Carole Shelley as his wacked out grandmother; and

the three child-actors who play Billy (I saw Kiril Kulish). It

feels decidedly odd to endorse a blockbuster London import in

this way, but, well, this show deserves to be seen.

----------------------------

Streamers

By David Rabe

Laura Pels Theatre

111 W. 46th St.

Box office: (212) 719-1300

What a happy surprise this

Roundabout revival of Streamers is. I vaguely remember

liking David Rabe’s play when it first appeared more than

three decades ago, but I haven’t seen or read it since and

who trusts memories that old? Turns out, it does tell a crackling

good story, as I remembered. More than that, though, I now see

that it’s one of those rare American plays that transcends

its strict realism due to the author’s sheer power of concentration,

his ability to follow through unflinchingly while tracing out

the consequences of his shrewdly drawn, volatile given circumstances.

Rabe never blinks in depicting this awful collision between soldiers

of different classes, races and sexual orientations, who are thrown

together in a Virginia army barracks while awaiting probable orders

to Vietnam. The outlines of the play’s scenario, thus described,

may easily sound like a yawn, since countless plays and movies

have exploited it for tendentious or sentimental ends. No easy

bromides or message-billboards for Rabe, though. His people are

dauntingly complex and multi-colored, and their terrible showdown

has broad allegorical resonance, even an air of tragic inevitability.

Scott Ellis’s production is smart, swift and unexpectedly

potent given that he keeps it rather cool until the climactic

violence. The actors are clear and penetrating, though some are

definitely stronger than others: J.D. Williams is dead-on as diplomatic

Roger, as is Ato Essandoh as menacing Carlyle, but Brad Fleischer

never quite finds the blustery uncertainty that sets Billy up

as a sacrificial goat. In any case, the strength of the ensemble

makes up for spotty deficiencies, and the people seated around

me were visibly shaken by the ending.

--------------------------------

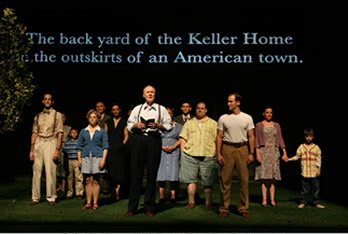

All My Sons

By Arthur Miller

Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

236 W. 45th St.

Box office: 212-439-6200

For obscure reasons, we seem

to need the British to show us how to breathe life into America’s

most heroic dramatist from the last century. This time it’s

the director Simon McBurney who has taken an Arthur Miller play

more than 60 years old and made it seem as fresh as a new Tony

Kushner work. I’ve seen All My Sons several times

before, and it has always seemed to me a rather straightforward

nugget of 1930s leftist moralism: the protagonist, Joe Keller,

is a heel because he knowingly sold defective airplane parts to

the Army Air Force during wartime and blamed his partner for the

crime, all (he says) so he could leave his sons a successful business—an

extremely moving but also rather tidy and obvious fable demonstrating

the necessity to look beyond callous capitalist imperatives to

our larger social responsibilities. Refreshingly, McBurney’s

production reveals a more complex tale where motives are deeper

and more contradictory than the characters’ self-justifying

bluster implies. Patrick Wilson’s Chris, for instance, the

dutiful war-veteran son whose uncompromising idealism drives Joe

to suicide in the end, comes across here not as a hapless naïf

but rather as another type of killer, ruthless in moral rigidity

where Joe was ruthless in profit-seeking. Diane Wiest as Joe’s

wife Kate and Katie Holmes as Ann, the girl Chris wants to marry,

are just as multifarious in their nuances. The production is also

a visual feast, with sumptuous animated projections against a

clapboard back wall and a Midwestern yard sketched with just the

right iconic objects (design by Tom Pye). In an interview in the

1990s, Miller said that All My Sons was being produced

more than many of his other plays, and he guessed it was because

of the high number of public investigations going on into official

malfeasance in business and government. Had he lived a little

longer, he would have understood another reason: the arrival of

apparently endless war, which has made the genre of returning-soldier

drama heart-breakingly apt. All My Sons is more than

a returning-soldier drama, but that aspect of it is hard to forget

as the climax arrives and drives home the pointed question of

how basic our civilized values are, and what it really means for

a nation to say, reflexively and habitually, that we must win

at all costs.