HotReview.org Editor's

Picks

Shows Worth Seeing:

Point Blank

By Edit Kaldor

P.S. 122

150 1st Ave.

Box office: (212) 352-3101

This small, quiet, unassuming

show by Budapest-born, American-educated Edit Kaldor packs an

oddly powerful punch. A petite, short blonde, Kaldor presents

herself as a nondescript, 19-year-old Finnish girl named Nada

who is unsure what to do with her life and goes tramping around

Europe taking pictures of strangers with a powerful zoom lens.

She assembles some 70,000 photos, many quite invasive, and has

been obsessively categorizing them in the hope that the organization

process might help her make some decisions about her future. As

she speaks, conducting a sort of quasi-public slide show aided

by a friend at a laptop, selected photos are projected onto two

large screens behind her, along with the elaborate organizational

folder-trees from her computer’s photo storage. Slowly we

realize that, her air of ordinariness notwithstanding, this girl

is consumed by her categorizing process. It has become a substitute

for actual experience. Traveling may teach some people greater

worldliness, but with Nada it seems to have exacerbated a profound

psychic isolation bordering on autism. She has no apparent ability

to feel passionate desire beyond the dry questions of categorization

in her folders, and she expresses no emotional connections with

actual people, only with the appearance of people in her candid

and interesting yet ultimately pseudo-intimate snapshots. The

resonance of all this for the rest of us in our screen- and image-obsessed

era is deep and troubling. Kaldor's anti-spectacle is also especially

forceful due to the crafty understatement of her modest affect.

This is a shrewd and perceptive artist from whom we are sure to

hear more in years to come.

-----------------------------------

Opening Night

By John Cassavetes

Adapted and directed by Ivo van Hove

BAM Harvey Theater

651 Fulten St., Brooklyn

Box office: (718) 636-4100

Ivo Van Hove’s Opening

Night is a rare theatrical quantity: a stage adaptation of

a celebrated film that is far and away better than the film. John

Cassavetes wrote and directed Opening Night in 1977 as

a rueful meditation on ageing: a vain and famous actress (played

by Gena Rowlands, Cassavetes’s wife) deliberately ruins

the last previews of a Broadway-bound play with drunken antics

and tantrums, then seems to suffer a mental breakdown triggered

by the accidental death of a girl seeking her autograph. It was

Cassavetes’s most personal film, and to see it today is

to recognize how unnecessarily blurred and hobbled it was by tedious

indulgences: long slogs through trite alcoholic stupors, important

story points muddied by the fixation on monotonous, brooding closeups.

At 146 minutes, the film feels an hour too long.

Van Hove says he is a Cassavetes fan. He

recognizes the filmmakers’ self-critical “adult”

atmosphere as akin to the complex, self-conscious aura he always

works to generate onstage. Importantly, though, he never saw this

particular film. He worked only from Cassavetes’s screenplay

in developing this adaptation with Toneelgroep Amsterdam, and

that’s no doubt why its story is so clear and engaging.

One sees for the first time how strong the subplots were involving

the actress’ first husband, the director and his wife, and

the dead girl, for they now shine through as penetrating and necessary

rather than as histrionic excrescences. The dead girl, always

a quintessentially theatrical touch, is now a much more forceful

and disturbing presence. The alcoholism is treated with a sense

of measure, one of a number of physical excesses that the play

shows up as conceits. And most crucially, the story’s multiple

locations are folded into a terrifically flexible unit set outfitted

as a rehearsal stage. Actors change costume there, actual spectators

are seated to one side, and camera operators shoot live video

of the action that is projected into large screens above, allowing

us to see almost everything in closeup and panorama all at once.

Thus technology handles the essential metadramatics of the tale,

its all-important self-consciousness about the theater, so the

actors are left free to enact the painful story, pushing it unforgettably

toward its bittersweet, beautifully indeterminate closure with

the prima donna reluctantly regaining reason. This is unquestionably

the high point of the BAM season so far: at the same length as

the film, it earns every minute and more.

-----------------------------

Billy Elliot: the Musical

Directed by Stephen Daldry, Book and lyrics by Lee Hall, Music

by Elton John

Imperial Theatre

249 W. 45th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

Curiously enough, this eagerly

awaited musical adaptation of the movie Billy Elliot

is almost as good as its hype. The story about a boy from a gritty

northern English coal-mining town who discovers a passion for

ballet was always irresistibly charming—just the sort of

triumph-against-the-odds, home-town-boy fairytale Hollywood got

rich on. The British adaptors of this show have been unusually

clever, though, in giving the tale strong theatrical legs. Elton

John’s rousing anthems and ballads pull all the right heartstrings

to make the audience cheer for both the boy’s success and

the victory of the union in the 1980s miners’ strike that

forms the play’s social background. But since that strike

ultimately failed—the Thatcher government famously broke

the union—the play’s impassioned cries of “solidarity”

have decidedly funereal overtones, and the story of the boy’s

individual triumph has particular poignancy against the bitter

failure of his loved ones’ collective action. This incongruity

gives the work a modest political complexity that other Cinderella

stories lack. The show is also wonderfully inventive. Director

Stephen Daldry (who also directed the movie) has inserted bizarrely

fluid choruses of cops and miners, for instance, who spread their

good and bad energy willy-nilly while sweeping through windows,

gyms and kitchens. At one point, Billy dances a strangely anomalous

pas de deux with his imagined older self, who seems to

provide the only viable adult role model he can muster. There

are half a dozen inspired creations of this kind, as well as superb

performances by (among others): Haydn Gwynne, who finds just the

right mixture of stoniness and congealed syrup for Billy’s

dance teacher; Carole Shelley as his wacked out grandmother; and

the three child-actors who play Billy (I saw Kiril Kulish). It

feels decidedly odd to endorse a blockbuster London import in

this way, but, well, this show deserves to be seen.

----------------------------

Streamers

By David Rabe

Laura Pels Theatre

111 W. 46th St.

Box office: (212) 719-1300

What a happy surprise this

Roundabout revival of Streamers is. I vaguely remember

liking David Rabe’s play when it first appeared more than

three decades ago, but I haven’t seen or read it since and

who trusts memories that old? Turns out, it does tell a crackling

good story, as I remembered. More than that, though, I now see

that it’s one of those rare American plays that transcends

its strict realism due to the author’s sheer power of concentration,

his ability to follow through unflinchingly while tracing out

the consequences of his shrewdly drawn, volatile given circumstances.

Rabe never blinks in depicting this awful collision between soldiers

of different classes, races and sexual orientations, who are thrown

together in a Virginia army barracks while awaiting probable orders

to Vietnam. The outlines of the play’s scenario, thus described,

may easily sound like a yawn, since countless plays and movies

have exploited it for tendentious or sentimental ends. No easy

bromides or message-billboards for Rabe, though. His people are

dauntingly complex and multi-colored, and their terrible showdown

has broad allegorical resonance, even an air of tragic inevitability.

Scott Ellis’s production is smart, swift and unexpectedly

potent given that he keeps it rather cool until the climactic

violence. The actors are clear and penetrating, though some are

definitely stronger than others: J.D. Williams is dead-on as diplomatic

Roger, as is Ato Essandoh as menacing Carlyle, but Brad Fleischer

never quite finds the blustery uncertainty that sets Billy up

as a sacrificial goat. In any case, the strength of the ensemble

makes up for spotty deficiencies, and the people seated around

me were visibly shaken by the ending.

---------------------------

Blasted

By Sarah Kane

Soho Rep

46 Walker St.

Box office: (212) 352-3101

Sarah Kane’s suicide

in 1999 was a great loss to the contemporary theater, but until

recently it has been very difficult for New York theatergoers

to understand why. The willfully unconventional plays Crave

and 4:48 Psychosis have been seen here in dreadfully

static and morose productions that have left an impression of

Kane as basically a documentarian of depression, a psychological

basket case with a flair for oratorio. Now there is finally more

to talk about, because of the long belated New York premiere of

Blasted, the play that made Kane notorious in Britain.

Written in 1995, Blasted is, on one level, an over-the-top

indulgence in repellent violence. With its mélange of rape,

torture, disease, terrorism, cannibalism and more, it outdoes

even the most brutal dramas of the “in-yer-face” genre

to which it belongs. The difference is that Kane also has deeper

political ambitions in this work, and they shine through in both

the public and private action, reverberating unforgettably from

the war raging outside the hotel room where the play is set to

the horrifying personal negotiations inside. Sarah Benson’s

lucid and superbly cast production isn’t for the faint-hearted,

but it should be seen by anyone interested in clawing for some

no-bullshit, redemptive air in the tunnel of ageless human violence.

Historically, it is also fascinating, and saddening, to recognize

that the violent legacy of Edward Bond and Howard Brenton actually

bore nourishing dramatic fruit for a brief moment in the 1990s.

Side note: the ingenious, spot-on set design by Louisa Thompson,

which must self-destruct halfway through the action, is alone

enough reason to see this show.

--------------------------------

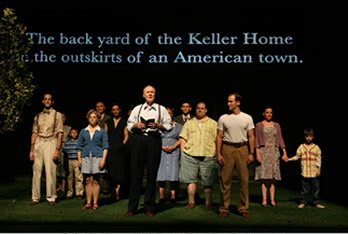

All My Sons

By Arthur Miller

Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

236 W. 45th St.

Box office: 212-439-6200

For obscure reasons, we seem

to need the British to show us how to breathe life into America’s

most heroic dramatist from the last century. This time it’s

the director Simon McBurney who has taken an Arthur Miller play

more than 60 years old and made it seem as fresh as a new Tony

Kushner work. I’ve seen All My Sons several times

before, and it has always seemed to me a rather straightforward

nugget of 1930s leftist moralism: the protagonist, Joe Keller,

is a heel because he knowingly sold defective airplane parts to

the Army Air Force during wartime and blamed his partner for the

crime, all (he says) so he could leave his sons a successful business—an

extremely moving but also rather tidy and obvious fable demonstrating

the necessity to look beyond callous capitalist imperatives to

our larger social responsibilities. Refreshingly, McBurney’s

production reveals a more complex tale where motives are deeper

and more contradictory than the characters’ self-justifying

bluster implies. Patrick Wilson’s Chris, for instance, the

dutiful war-veteran son whose uncompromising idealism drives Joe

to suicide in the end, comes across here not as a hapless naïf

but rather as another type of killer, ruthless in moral rigidity

where Joe was ruthless in profit-seeking. Diane Wiest as Joe’s

wife Kate and Katie Holmes as Ann, the girl Chris wants to marry,

are just as multifarious in their nuances. The production is also

a visual feast, with sumptuous animated projections against a

clapboard back wall and a Midwestern yard sketched with just the

right iconic objects (design by Tom Pye). In an interview in the

1990s, Miller said that All My Sons was being produced

more than many of his other plays, and he guessed it was because

of the high number of public investigations going on into official

malfeasance in business and government. Had he lived a little

longer, he would have understood another reason: the arrival of

apparently endless war, which has made the genre of returning-soldier

drama heart-breakingly apt. All My Sons is more than

a returning-soldier drama, but that aspect of it is hard to forget

as the climax arrives and drives home the pointed question of

how basic our civilized values are, and what it really means for

a nation to say, reflexively and habitually, that we must win

at all costs.