Designing The Great Game:

A Conversation with Pamela Howard

By Terry Stoller

Pamela Howard was the project designer

for the latest venture by artistic director Nicolas Kent at London's

Tricycle Theatre--a series of commissioned plays about Afghanistan,

spanning the mid-19th century to the present. The festival's title,

The Great Game, refers to the historic playing for power

in Central Asia by the British and the Russians. Kent and Indhu

Rubasingham, assisted by Rachel Grunwald, staged a dozen short

dramatic plays for a three-part program, which could be viewed

separately on weekday evenings or all in one day on "marathon"

weekends in spring 2009.

A cast of fifteen actors, featuring

Paul Bhattacharjee, Michael Cochrane, Jemma Redgrave, and Jemima

Rooper, played some ninety roles. In addition to the plays, the

Tricycle hosted art exhibits, discussions, and films. The sweeping,

fascinating play cycle takes a sharp look at the complex history

of Afghanistan--the imperialist aggression and intervention, the

violent internal struggles.

Part 1 (1842-1930), subtitled Invasions

and Independence, takes us back to the first Anglo-Afghan

war in Bugles at the Gates of Jalalabad by Stephen Jeffreys,

when thousands of British troops have just been massacred. Yet

the British wind up calling the shots in Ron Hutchinson's Durand's

Line, a battle of wills in the 1890s between British India's

Foreign Secretary and the Amir of Afghanistan over establishing

the country's borders. After a brief fast-forward to the 21st

century and contemporary strategy at the British Foreign Office

in Amit Gupta's Campaign--which harks back to the democratic

ideals of Afghanistan's King Amanullah--Part 1 concludes in 1929

outside Kabul, with the reformist King overthrown and literally

stuck in a snowdrift in Joy Wilkinson's Now Is the Time.

In Part 2 (1979-1996), Communism,

the Mujahideen and the Taliban, David Edgar's Black Tulips

chronicles the aspirations and tribulations of the Soviet army

during its occupation of Afghanistan. Blood and Gifts

by JT Rogers sheds light on some of the resistance: the Americans

are arming Mujahideen to fight the Soviets. Communist President

Najibullah stayed in power for a few years after the Soviets left

Afghanistan. But he is under house arrest in a U.N. compound in

David Greig's Miniskirts of Kabul, which "imagines" a

conversation with the ousted leader during his final days and

recounts his gruesome death in 1996 at the hands of the Taliban.

In a vivid conclusion to Part 2, the Taliban, who are in charge,

mete out a terrifying form of justice in The Lion of Kabul

by Colin Teevan.

Part 3 (1996-2009), Enduring

Freedom, opens with Ben Ockrent's Honey and the CIA

trying to get its weapons out of Afghanistan. Five years later,

the Taliban have made further incursions, al-Qaeda is strengthening,

and the Northern Alliance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud is assassinated,

two days before the bombing of the Twin Towers in New York City

(shown in a stunning coup de théâtre). It's 2002 in Abi Morgan's

The Night Is Darkest Before the Dawn, at a field of poppies

south of Kandahar. As the title suggests, there's a chance for

better times. The Taliban are gone, and an American from an aide

organization is in rural Afghanistan to fund a girls' school.

But there can be pitfalls when outsiders interfere in local matters,

and in Richard Bean's On the Side of the Angels, brokering

land rights in the tribal culture results in moral compromises

and a tragic end for British NGO workers. Finally, Simon Stephens'

Canopy of Stars comes full circle, with British troops

in Afghanistan--and one soldier's personal battle back home to

justify the continuing intervention in that country. Along with

the plays are short scenes by author Siba Shakib and verbatim

pieces by Guardian journalist Richard Norton-Taylor on

the resurgence of the Taliban.

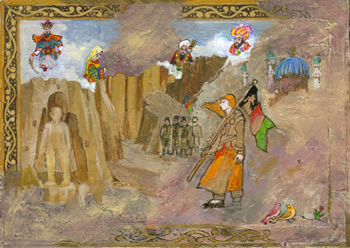

None of the plays were written when

Pamela Howard signed on to the project and began to develop an

overall concept for the production. She created a backdrop for

the plays: a beautiful mural with figures from Afghanistan's history.

In the foreground is Malalai, the young woman who carried a "flag"

for the Afghan soldiers in the battle of Maiwand during the second

Anglo-Afghan war. Malalai comes to life in a duologue by Shakib.

Howard talks in the following interview about the genesis of that

mural and the challenges of designing a project of this magnitude

for the Tricycle, a 235-seat theatre.

Pamela Howard is a designer and director.

She has worked as a stage designer in the U.K., Europe and the

U.S. on more than 200 productions and is the author of What

Is Scenography? (Routledge). In 2008, she was awarded the

OBE for services to drama. The interview took place in New York

City in May 2009.

------------------------------------

Terry Stoller: When Nicolas

Kent proposed this particular project, what did you think about

the challenge of so many plays? What drew you to the project?

Pamela Howard: Nick came

to visit me where I live, down in Sussex. Nick and I, in various

different ways, are both politically aware and probably committed

to trying to use our art to do something. And he said to me, "I'm

planning a big project about Afghanistan," and I said, "Oh, I

might be interested in that." And that was all that was really

said. He didn't say, "Oh, yes, I'd like you to do it." Then a

few weeks later, he came back and said, "Do you want to do it?

It's such a huge project, and I couldn't entrust this to somebody

young. I need someone terribly experienced because the plays will

not be written by the time you have to get something together.

And I need somebody who can make an overall concept of the whole

thing. And then you can have an associate designer, and you could

individually do whatever plays you wanted." That's when I thought

of bringing Miriam Nabarro in, because she'd had a lot of experience

working for NGO charities abroad.

TS: Isn't this rather

unusual, to design something before you have the play?

PH: It's a bit odd. But

I had a clear idea in the very beginning, which was about Afghanistan--death.

Nick showed me a piece in the newspaper about the painter Mashal,

who'd been painting this picture of 500 years of Afghanistan in

the bazaar at Herat. He was a famous fine-art painter, and he

had taken his inspiration from the early Persian miniatures, known

as the school of Behzad. But the Taliban came and forced him to

watch while they whitewashed it out. Nick said to me, "Do you

think we could try and stage that, and show the actual whitewashing

of the wall?" That was really how it started.

I did various versions of the mural. I

came across this character called Malalai, who could have been

me. I could have been the Afghani shepherd girl going out into

battle in 1880, with the flag: "Come on, get rid of the British!"

I loved the character of Malalai and always wanted her to be central.

I think Nick got worried about the amount of detail that was going

into the mural, and he thought it would be very distracting for

the action. Gradually I refined it more and more. Then he wanted

to somehow try and show the Twin Towers, but we didn't really

know how to do it. And suddenly I thought if the mural wall is

painted white, but you could still see the picture underneath,

you could project the Twin Towers.

In my book, What Is Scenography?,

I've written a lot about space and how you use space in theatres,

and one of the things I wanted to do at the Tricycle was to use

every bit of the space, to clear the whole thing out. I thought

with all these plays, one of the things I need to do is clear

out the sides, clear out the back and really look at what space

is available. And as soon as I did that and measured up what the

back is, I saw that the mural could go all the way back. And I

think that was the beginning of the whole story of this. Because

as soon as we saw it could go back, I saw that something could

fall in from the sides that might look like the Twin Towers, but

I wanted it to turn into a poppy field. I wanted to associate

opium, poppies and death with the bombing of the Twin Towers and

death. So that one results in the other because the events were

connected--the killing of Ahmad Shah Massoud was two days before

9/11 and the bombing of the Twin Towers, then it goes to Afghanistan

and becomes a field of poppies.

I didn't know then that Abi Morgan's play

would come in and actually be the perfect play. I was just overall

thinking of the big images because at the time I had no idea of

the sequence of events. What I think is brilliant about The

Great Game is that Nick has managed to embroider the whole

thing into a sequence that works with the wall. Because all he

did was say to the writers, you've got 30 minutes to the second,

no longer, no shorter, and this is the period I want you to do--but

the writers could come up with anything. And the fact that they

appear to be coherent …

TS: And they echo one

another and build the story.

PH: Absolutely. And they

link. I have to give Nick total, one hundred percent credit for

that because he has done the most brilliant job. And if you didn't

know how serendipity it all was, you'd think it was all planned.

I'm full of admiration for the way that Nick, with Jack Bradley,

the literary adviser, has managed to manufacture something. But

that was the idea always--I thought if I think of Afghanistan

overall, I could think of tragedy, but I could think of beauty

and the seduction of beauty, and poppies and opium and death.

It's like a seduction, isn't it? That's part of its tragedy. So

in Abi Morgan's The Night Is Darkest Before the Dawn,

when the American says you've got to grow wheat, the Afghanis

just laugh at him. They think, "No, it's worth too much money,

the poppies. We're not going to grow wheat. Are you joking?" It's

too big an industry, and also, of course, the West is buying into

it.

TS: Back to the mural:

Siba Shakib wrote a piece about Malalai. Did you ask her to do

that?

PH:

I didn't ask her to do that. I sent Siba a picture of the mural,

and then she wrote the monologue about Malalai. I was communicating

with Siba and asking her about historic figures, and she told

me about the Queen of Herat. But what happened was when Siba wrote

the Malalai story, I'd already done the mural painting with Malalai,

and then we ran out of money and we couldn't do the costume that

I had painted, which is like a piece of armor, with a skirt and

trousers. Then I remembered that at home, I had a real Afghan

coat, which is the green coat that the actress wears. Miriam said,

why don't we put her in that green coat and repaint the mural

wall to match your coat, which is what we did. Then we had to

borrow something from the National Theatre for the Queen of Herat

and paint her to match the thing that we borrowed.

PH:

I didn't ask her to do that. I sent Siba a picture of the mural,

and then she wrote the monologue about Malalai. I was communicating

with Siba and asking her about historic figures, and she told

me about the Queen of Herat. But what happened was when Siba wrote

the Malalai story, I'd already done the mural painting with Malalai,

and then we ran out of money and we couldn't do the costume that

I had painted, which is like a piece of armor, with a skirt and

trousers. Then I remembered that at home, I had a real Afghan

coat, which is the green coat that the actress wears. Miriam said,

why don't we put her in that green coat and repaint the mural

wall to match your coat, which is what we did. Then we had to

borrow something from the National Theatre for the Queen of Herat

and paint her to match the thing that we borrowed.

TS: When the production

opens, the artist is finishing up the mural, and you're to believe

there's other stuff to finish.

PH: That's because I had

to try and not make too much detail above and behind the actors.

And I think that worked, particularly because lighting designer

James Farncombe manages to light it in such a way that it just

becomes a landscape behind them. In the upper right corner is

the mosque that was built by the Queen of Herat that she refers

to, the blue mosque. And in the beginning, you see the artist

up the ladder, and he's finishing the drawing. From the top left

is Tamerlane, then the Queen of Herat, then Genghis Khan, then

Shah Durrani. I tried to make them look as if they were done in

the style of the Persian miniatures.

TS: The mural wall [approx.

16 1/2 ft. wide by 14 ft. high] is so striking when you walk into

the theatre. Then when it starts getting whitewashed, that really

has a visceral effect.

PH: People are shocked

by it. One of the things I wanted to say--and it's a theme I've

used quite a lot in different productions, because I direct almost

as much now as I design--is about how frightened people are of

art and of artists. It's about censorship, burning books. But

particularly artists become targets, and you see it in the whole

Palestinian question that's going on. In any situation where you

have repression of any sort, sometimes art becomes the spokesperson

for that particular situation because you can say things in visual

arts that you can't say either in writing or in plays. That becomes

part of the responsibility of an artist in a political climate.

TS:

When we spoke at the Tricycle about the open wing space, you talked

about your concept of "burkas over furniture." Could you tell

me more about that?

TS:

When we spoke at the Tricycle about the open wing space, you talked

about your concept of "burkas over furniture." Could you tell

me more about that?

PH: From the beginning,

when I knew there were going to be twelve plays--though I'm a

visual artist, I'm very practical--I thought, "How are you going

to bring all this stuff on and off?" When you look at pictures

of Afghanistan, you often see furniture being thrown out of houses

where it's been bombed. And you think, this is somebody's chair

that they've sat on. And there's a sense of things being thrown

out and waiting to be reused. So I said to Nick, "What if the

furniture is always on either side?" (At that time, we thought

the furniture for all three parts would be there, but it turned

out to be not practical. That's fine. In fact, it's much better.)

And then I thought, "It's going to be too distracting if we're

looking at all these bits and anticipating how they might be used."

I said, "What if the furniture is in burkas?" I'd been looking

at camouflage. So I imagined that there would be a stage and that

we would build up the stage a little bit; if we could use something

from underneath, something from on top, something from the sides,

and something from the back, we'd be using every bit of the space.

And I imagined a hard stage, which would be the acting area--and

an evocation of camouflage, sand, and I thought we might make

hessian "burkas," furniture in burkas at the sides, just like

the women are in, waiting.

TS: The Rolls-Royce at

the end of Part 1 was very impressive. With that you see the use

of transformative furniture: the couch from Amit Gupta's Campaign,

set in the Foreign Office, becomes the backseat of the Rolls in

the play that follows, Joy Wilkinson's Now Is the Time

about the exile of Afghanistan's King Amanullah in 1929.

PH: I loved that play

that Joy Wilkinson wrote. And I got completely carried away by

Rolls-Royces. I researched Rolls-Royces, and I also went to the

Foreign Office and had a look around. And I walked into one office,

and I saw this red Chesterfield sofa, and I thought, "That looks

like the back seat of the Rolls-Royce." And that's what gave me

the idea.

TS: The sets had to be

done very quickly. How much time did you have to develop that?

PH: Not a lot. I think

I got the play in the end of January; we started rehearsing in

February. Although Joy had told me she wanted to set it all in

a Rolls-Royce. I'd been looking at Rolls-Royces, and I was thinking

snow drifts; the thing is stuck in a snow drift. Originally I

thought the whole of the front of the Rolls-Royce might be in

a trap, and they'd open the trap and it would be snow. I made

several models of it, and I realized actually we only need a wheel

in the trap, so we cut all the rest--and we need the thing for

the driver. Then I went to the Foreign Office and I saw the sofa,

and I thought if the guy in the Foreign Office in Campaign

has a red leather chair, we could turn that around, and that could

be the driver's seat.

TS: I had never seen a

sandbag bunker before, which is used in the last play, Canopy

of Stars by Simon Stephens.

PH: I have a neighbor

whose wife, my friend Susan Harper, was at art school with me

when we were both 16. She's a decorative artist, and she helped

in the construction of the mural; she drew out the border for

me. Her husband is very good at making miniature things. He comes

from a military family, and he knew about sandbags. So I gave

him little bits of bandage and little bits of modeling clay, and

he made all these little model sandbags for me. I got all the

neighbors involved.

TS: During the blackout

of Canopy of Stars, the poppies disappear for the final

scene.

PH: They are actually

there, but they're not lit. I always thought what was good about

the way Nick constructed the plays was that The Great Game

didn't end on a big note, and it ended with the real tragedy of

Afghanistan: that you have this war, but actually it's a young

man and a young woman and they've got nothing to say to each other.

That's the terrible destruction of war--what happens between two

people. I always thought from the very beginning, if the back

of the Rolls-Royce is a red sofa, the end of the play [cycle]

should be a red sofa. In both the Rolls-Royce play [about the

King's exile in 1929] and the last play, Canopy of Stars

[set in the present], there is the sense of finality, of tragedy,

and people seeking comfort in a sofa. I like that you have this

huge wall falling down, you have all of that, and it's reduced

and reduced and reduced, and then you have the bunker, and then

you have the blackout scene, and then the lights come up and it's

just a sofa. Director Indhu Rubasingham at one point said, "Are

we missing something? Shouldn't we end with a great finale?" And

Nick and I said in unison, "No, it's just got to be one man on

a sofa. That's all." Because that's the awfulness of it.

TS:

Some of the plays were single set, and then you also had to deal

with different settings within a very short play, especially the

four settings in Honey by Ben Ockrent: Islamabad's U.S.

embassy; Defense Minister Massoud's office in Kabul; Massoud's

bedroom in northern Afghanistan; and another room in the house.

TS:

Some of the plays were single set, and then you also had to deal

with different settings within a very short play, especially the

four settings in Honey by Ben Ockrent: Islamabad's U.S.

embassy; Defense Minister Massoud's office in Kabul; Massoud's

bedroom in northern Afghanistan; and another room in the house.

PH: Part of the discussion

was having all those scene changes in a thirty-minute play. However,

the question was how you did it in the end. I had to try and find

elements that would very simply make these different locations--and

funnily enough, Honey did work quite well.

TS: Especially because

of the connecting monologues, with the character narrating downstage.

PH: Actually, I thought

it was really rather a good play.

TS: I did too. And that

play is central for the design afterward of the projection of

the bombing of the Twin Towers and the mural wall falling down.

PH: Of course, I didn't

know that at the time. That's what I thought was so brilliant.

That Nick was able to bring it in exactly there. Originally there

was a thought that if we had the mural, the whitewashing scene

would happen all at the beginning, and the whole of the plays

would be done against white, and I'm really glad that didn't happen

because you need time to absorb what that is.

TS: Yes, it's shocking

when the mural begins to get painted over, and you get the double

shock when you come back for Part 3, and it's all been whitewashed.

PH: So you can build it.

But of course in the beginning, we certainly didn't know that.

TS: I'm in awe that you

did that without knowing what the plays were.

PH: So am I. It's so unlike

the way I work. I have done very big-scale work. On the whole,

I can bring big things together. I suppose the signature of my

work is to do things very simply that appear to be hugely complicated.

TS: What was wonderful

about Canopy of Stars was that it was very simple--the

sandbag bunker, the blackout, a sofa in a house in Manchester--and

yet the places changed dramatically. Is there anything else you'd

like to tell me about?

PH: I hope Nick gets proper

recognition for this thing. Because what he's done is opened up

the debate. The question you have to ask at the end is, "What

the hell are we doing there?" And I suppose every country would

be asking the same thing. Without making a didactic polemic, he's

posed the question by the consequence of what is being shown.

The conclusion anybody must come to is, What's it all about? And

I think back to Ron Hutchinson's Durand's Line [in Part

1, set in Kabul in 1893], when Foreign Secretary Durand says,

"A thing has to be defined … That's what this whole century has

been about." The Amir says [about the British proposal for Afghanistan's

border], "But what if we move the line?" And you suddenly realize

the enormity of this whole thing that's sucked the world in, and

the death and the destruction, and it was all about a line being

drawn.

TS: I loved that play.

I never thought of maps in that way.

PH: You've got to have

maps, Durand says, 'cause you've got to "stick pins in it."

TS: I never thought of

a map as something arbitrary. Of course it is.

PH: And when the Amir

says, Well, give me this, I'll draw England for you. I don't like

where Scotland is, so I'll move it--it's a very moving moment.

And the other thing, I'd say finally, I do think that Nick and

Indhu between them cast it brilliantly. In the end, it's the quality

of that ensemble acting, and they were very well cast. You think,

that small theatre, and all those plays, and those people and

casting of that quality--it's something. So I can only say it

nearly killed me, but I'm glad to have been part of it.

----------------------

Photos courtesy of Pamela Howard and copyright

John Haynes.