On The Cyclist:

An Introduction

By Balwant Bhaneja

For the past four decades, Vijay Tendulkar

has been the most influential dramatist in India. His plays written

in Marathi, the principal language of the state of Maharashtra,

are continually produced all across the country, and have been

translated into other regional languages and English. A lifelong

resident of Mumbai, Tendulkar (b.1928) is also a novelist, literary

essayist, journalist, television and screenplay writer, and social

activist. (1) Nobel Laureate V.S. Naipaul has called him India's

best playwright. (2)

Tendulkar is author of thirty full-length

plays, twenty-three one act plays, several of which have become

classics of modern Indian theatre. (3) Among his well-known plays

are: Shanta! Court chalu ahe (Silence! The Court

is in Session, 1967), Sakharam Binder (Sakharam,

the Bookbinder, 1972), Kamala (1981), and Kanyadaan

(The Gift of a Daughter, 1983). His Ghashiram Kotwal

(Ghashiram the Constable, 1972), a musical combining

Marathi folk performance and contemporary theatrical techniques,

is one of the most performed plays in the world, with over six

thousand showings in India and abroad. New York's Indo-American

Cultural Council dedicated October 2004 as a tribute to Tendulkar's

prodigious literary contributions, presenting in English a wide

range of his plays and films.

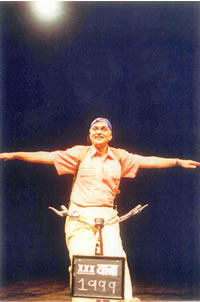

The Cyclist was intended to be

Tendulkar's last play, and perhaps his ultimate comment on himself

and the reality surrounding him. In 1991, Tendulkar, in his early

sixties, had written 28 full-length plays, his work singularly

recognized for its intellectual integrity, innovative form and

content. His plays have generally dealt with themes that unravel

the exploitation of power and latent violence in human relationships,

seeking always a well-deliberated resolution. The desire to write

an allegorical play denoting life's journey must have been a tempting

one. Despite its numerous productions, The Cyclist has

continued to confound its directors and audience. Critics have

not been sure whether the play is a metaphor for contemporary

Indian reality or an allegory about the journey of life.

As an intended last play (4), The Cyclist

is different from Tendulkar's large body of work. It is a skillfully

crafted, uninterrupted piece about the adventure of life told

through a cyclist's journey. As an experimental playwright, Tendulkar's

every play, in its form and structure, is different from the previous

one. This complex theme he takes head on, and tackles with a simple

form and language -- an episodic structure and naturalistic mot

naif dialogue. Life's complexity can perhaps be best understood

when told in simple terms. In this, Tendulkar joins other great

journey writers such as Homer (The Odyssey), Voltaire

(Candide), Ibsen (Peer Gynt), and Beckett (Waiting

for Godot).

The Cyclist is not about one but

three journeys: geographical, an historical journey of the bicycle,

and a psychological exploration. A young man is about to start

a "world trip" on his bicycle. There is no specific

geographical location in which the play is set, but a place from

which he is trying to get away. He dreams of distant lands, oceans

and mountains, wanting to see exotic places, meet interesting

people.

The geographical journey is at the same

time the story of the development of bicycle itself -- the cycle

as a symbol of progress, opening new horizons for the society

despite all the obstacles placed in its way to stop its advancement.

The adventure gets darker and darker as the journey progresses,

the Cyclist facing difficult elements both natural and human.

It unravels man's dehumanization through a series of encounters

which, though often extravagantly comic, tend to become illogical

and bizarre as we move deeper into the play.

In journey narratives, the obstacles encountered

are generally surmounted; in The Cyclist the process

is reversed, the expectation of certainty whimpering into nothingness.

It's only in the later part of the Cyclist's trip that we come

to find out that this is essentially a metaphysical journey --

a journey of the mind. Buried deep in the play is the grand existential

question: "where I came from, where I am going"? -- life's journey

in search of elusive truth.

The play generates a train of events manifested

on stage through a series of slapstick situations. Tendulkar lets

his character Cyclist play straight, whereas those he encounters

on the way come in a group as hoodlums, in pairs as the Lords

of Earth and Sun, or single as Sage, or Actor. These latter are

written in exaggerated manner. Perils of the journey are mixed

with uneasy laughter.

Tendulkar has described his plays as about

the reality surrounding him: "I write to let my concerns vis-a-vis

my reality -- the human conditions as I perceive it." The reality

in The Cyclist, however, with its layered journeys, gets

elevated to a level transcending geographical and cultural boundaries.

For example, all the characters in the play have been consciously

given symbolic names. e.g. X,Y, Z. or such titles as Ma, Pa, Lion,

Ghost, etc. And even the central protagonist the Cyclist is neutrally

called the Main Character.

Tendulkar has said that it is the content

of his work that determines the form. He is precise about directions

for staging the play. The script points to a minimalist setting

-- an exercise bike as the sole prop. The bald patch on the Cyclist's

head, which viewers see in the last scene, is to ensure that the

play is about an adult and is not mistaken for any children's

fantasy. Again, the use of coarse language at the beginning, in

a violent crowd scene, reinforces the playwright's intent about

the adult nature of the play. Most directions are embedded in

the dialogue which in its naturalistic idiom is marked by short

sentences, often half finished.

In The Cyclist, unlike most of

Tendulkar's other plays, there is no strong female character.

Instead, it's a Mermaid (a woman with a fish's torso) who eventually

strips the Cyclist to his flesh and bones, having swallowed his

wet clothes. Mermaid's seduction of the Cyclist is that of Oedipus,

a composite of mother, girlfriend, and an enchantress.

Main Character: Why

are you laughing?

Mermaid: Because your

clothes are in my stomach!

Main Character: Where?

Stom…No, this can't be!

Mermaid: If you got

the clothes, you'll run away from me, somewhere far…thinking

that I swallowed your clothes (in a guilt-ridden voice)

Main Character: (not

believing and with fright) Swallowed them? (a bit pathetically)

Ridiculous…I have to go on my travel…the world journey…by cycle..oh,

such an old dream of mine…

Mermaid: (in a dreamy

voice) I'll guard them for nine months in my womb. Then

I'll give birth to a lovely child. A child in your clothes,

handsome as you. He'll call you Pa…Pa, Papa, and me…Ma, Ma….

Referring to the pointless search for meaning

in his plays, Tendulkar has said, it's a "jungle in which you

can always enter, but has no way out." Unlike his other plays,

which often have a pall of gloom over them, The Cyclist

was written in an upbeat frame of mind. Despite all the travails

and troubles that the journey brings, the Cyclist does not give

up. As he remarks: "A journey is a journey. It has to be completed.

Mine will not be affected by any loss or pain." The Main Character

has the will to overcome obstacles. And even when the Cyclist's

determination dissipates and the situation is hopeless, his cry

for help is rewarded. Pa appears out of nowhere as a shining light

with his clichéd advice to get him out of his pickle. The best

solution Pa can offer in one Zen-like moment of revelation --

(when everything fails) "Do nothing, sometimes that's all you

need to do."

The journey has to be completed even when

we don't know its ultimate destination (except one's mortality).

There are two options. It could be an open-ended journey to a

place different from where one started; or it's a completed journey

that culminates with a return home -- to the place one began.

In Eastern philosophy, the path is more significant than the destination.

Injured and exhausted, stripped of his

clothing, the Cyclist lays naked beside his bicycle in the end.

He curls in a womb-like position and falls asleep. It is not clear

whether he will be up the next day to continue his adventure.

Tendulkar has declined comment on the play

except to say that it speaks for itself. In my correspondence

with him (which spans a decade), he made only one remark comparing

the situation in India in 1999 to the play: "Life here is as in

the Cyclist. It will never change. Each day we ride our old, dilapidated

wheel-less cycle and go places. Breath-taking static activity."

---------------------------

Endnotes

(1) Two important sources on Vijay Tendulkar

are: Shoma Choudhury and Gita Rajan (eds.), Vijay Tendulkar,

New-Delhi: Katha, 2001, and Vijay Tendulkar, Sri Ram Memorial

Lecture -- The Play is the Thing, New-Delhi: Sri Ram Centre

for Performing Arts, 1997.

(2) Khushwant Singh, "Storm in a Chat Show," The Tribune,

March 31, 2001.

(3) For English translations of Vijay Tendulkar's work, see: Vijay

Tendulkar (with an Introduction by Samik Bandyopadhay), Collected

plays in Translation, New-Delhi: Oxford University Press,

2003, and Vijay Tendulkar, Five Plays, Bombay: Oxford

University Press, 1992.

(4) A decade later The Cyclist was followed by another

Tendulkar play, The Masseur, two novels, and his first

play in English, entitiled His Fifth Woman (written for

the Lark Theatre in New York as part of the Tendulkar festival).