Courtside Drama

By Rebecca Fried Weisberg

Three Seconds in the Key

By Deb Margolin

Baruch Performing Arts Center

(closed)

Three Seconds in the Key, a new play by Deb Margolin,

opens a window into the inner life of a housewife dying of Hodgkins

Disease. But the play is no syrupy Terms of Endearment clone.

Rather, in Margolin’s moving one-act, the main character

-– known only as the Mother -– shares her raging emotions

and racing thoughts in an intimate shared hallucination. The play

is a series of vignettes that rise out of the confused caverns

of the Mother’s mind with a paradoxical crispness, like

scenes from a sharply real dream where the oddest things just

happen to occur. At the heart of the play is her imaginary interaction

with a fictional black basketball player from the New York Knicks,

which escalates into a series of verbal tournaments where she

confronts her deepest crises of faith, identity, and strength.

The New Georges theater company recently presented the first

full production of this evolving work -– which began as

a solo piece in Deb Margolin’s well-known downtown idiom.

Its latest incarnation incorporated an unusual setting that vividly

merged the Mother’s real life and fantasy life. The theater

was structured to resemble a small basketball stadium, with arena-style

seating arranged in three-quarter round. The center of the floor

was an orange and blue rubber court, encircled by glossy wood,

with a basketball net mounted on the front of a monitor that later

served as both a scoreboard and a television. In the center was

an orange print couch and coffee table, making up the living room

where most of the drama happened. This design meshed the two worlds

of the play very well: the Mother’s house and the television

world of basketball, with the basketball action increasingly melded

with the Mother’s everyday experiences.

All of the acting was strong, with a powerful and nuanced performance

by Catherine Curtin as the Mother. Evoking hilarity and grief

in equal measure, Curtain led the audience on a sometimes random

and bizarre journey, and she was so captivating that one agreed

to go along for the ride, following wherever the Mother’s

mind went. Alexandra Aron’s directing also clearly shaped

the character development and helped unify a somewhat mismatched

ensemble. Aron skillfully molded the dramatic architecture (as

designer Lauren Halpern did the physical environment), enabling

the sweat of the basketball game to infiltrate the Mother’s

living room without ridiculousness. It was Margolin’s writing,

however, that left the strongest impression.

Three Seconds in the Key begins with a twenty-minute

monologue, in which the Mother pads into the spotlight in bathrobe

and fuzzy slippers and ruminates on her depressing inability to

smoke marijuana, despite its curative effects on the nausea that

comes with her chemotherapy. “I can’t smoke pot,”

she half giggles, half drones in a kind of hammy deadpan -–

making us wonder if her disordered yet acute mental state is supposed

to illustrate the veracity of her statement. Her barbed, darkly

comic monologue is rooted in the absurd and often sad physical

and psychological situations that arise when the body fails. The

comedy is marbled with a startling poetry woven into the very

conversational speech. The Mother describes how in the night shadows

of her balcony, the joint she recently smoked resembled “a

star that had dared to come close to my face; a little minnow

in the darkness.” As her words paint the pictures in her

mind for us, the Mother draws us in, and we begin to feel a certain

communion with her—enhanced by the knowledge (which most

of the audience has gleaned from the program or from reviews)

that the piece is semi-autobiographical, based on the playwright’s

own experiences battling cancer.

The Mother tells of an evening when she formed a striking spiritual

connection with a black Preacher who seemed to speak to her directly

via public access television. Her narrative bursts into theatrical

life as a tall, dark-suited black man (played by Avery Glymph)

appears in the flesh in front of her, back to the audience, not

quite in the spotlight nor quite out of it as he hovers at the

entrance to the stage near the center aisle. Together, they fervently

recite a litany of beliefs about the Lord. “The Lord does

not care for your fancy clothes… your jewels… your

car.” Essentially, he sees right through you, to your very

essence. Although she has no firm religious beliefs, the Mother

is mesmerized by this man: both by the image he creates of God

stripping a person down to his most basic self, and by the Preacher’s

own passion and honesty in revealing his deepest, rawest beliefs

for all the world to see. However, at the very moment of the Mother’s

rapture, the spiritual, almost mystical nature of the experience

is quickly punctured by a too-human absurdity. The Preacher has

been counting his central beliefs on his fingers, raising each

finger one at a time, and the Mother is shaken from her reverie

as she realizes that in his unworldly innocence he will enumerate

a sacred spiritual belief with the ultimate vulgarity: the middle

finger, raised with force. That, says the Mother, is the last

thing she remembers, having then floated off into intoxicated

laughter at the ludicrous contrast between the Preacher’s

beautiful faith and his unknowing “Fuck you” to the

faithful.

The comedy in the play brings laughter that is excruciating:

even while finding humor in the Mother’s escapades (and

admiring her ability to do so), we feel her anguish. Also, as

she tells us, laughing is like bleeding -– "cleansing,

painless, fatal." While this idea may seem perplexing at

first, our language is replete with analogies between laughter

and death: “I died laughing” or “That kills

me.” Like bleeding, laughter destroys our physical control,

seemingly draining our life force. As the words spill out of the

Mother, it is not just the laughter that provides relief; she

exults in words, spilling them liberally, and the hemorrhage of

poetry purges her demons while renewing her strength. This dichotomy

is the play’s fundamental irony: sometimes salvation lies

in isolating and embracing the regenerative qualities of our most

destructive moments. Indeed, the play’s meditation on the

nature and purpose of faith is its focal point, and it is drawn

out more deeply as the Mother develops her relationship with yet

another unnamed character, the Player.

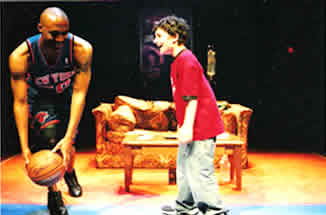

The Player is introduced along with his equally anonymous teammates

immediately after the Mother’s first monologue. In an abrupt

segue, the audience is transported to a live basketball game.

Fluorescent light glares, hip-hop music blares, and five tall,

muscular basketball players come running onto the court, dribbling

and passing the ball while pictures of their faces bob across

two monitors on stage.

At the same time, the Mother’s little boy enters, and mother

and son gaze at an imaginary television, experiencing this basketball

game as the TV audience. The blissfully technical sport provides

a short respite from illness and pain. For a moment, all that

matters are the speedily accumulating points, the sheer athletic

power of the players’ bodies, the emotional but ultimately

unimportant hairsplitting interpretation of the rules. The Mother’s

obsession with her inner life and the words that swirl around

there contrasts starkly with her participation in this display

of mainstream sports culture. Her unlikely affinity for the sport

makes the team chant resonate even more loudly; it comes to serve

as a metaphor for her battle for her life.

I refuse! I refuse to lose! I refuse to fail! I refuse to die!

I refuse to be afraid! I refuse to be taken! I refuse!

Frequently, sports metaphors seem trite: in applying the lessons

of everyday activities like baseball and football to life’s

deeper struggles, they can detract from the weight -– and

the tragedy -– of individual stories of hardship. In this

case, the unusualness and physicality of the situation refreshes

the metaphor and transforms it into a powerful artistic tool.

As the team breaks off the chant and the other athletes recede

into darkness, the Player (played by Samuel R. Gates) walks straight

into the living room, breaking through the imaginary boundaries

between the Mother’s home and the surrounding realms of

fantasy. When the Mother catches sight of the Player, she is arrested,

breathless, and slaps him to prove to herself that he cannot be

real. The sound of skin on skin reverberates, its sharp echo symbolizing

a turning point for the Mother. Suddenly, her mental extravagances

have created a channel for salvation to help her to escape from

the dark chambers of her mind.

The

Mother’s dialogues with the Player are interspersed with

her solo musings and conversations with her son, as well as the

team’s conflicts as they stumble through a losing season.

These dialogues are central and, interestingly, they mirror her

spiritual experience with the Preacher. In their first spoken

exchange, the Player tells her, “I got your call, Mother,”

and we are reminded of the way the Preacher came to her in a moment

of need, alone in a scary, smoked-out stupor. As the Mother said

earlier, God comes to you when you’re alone, and while God

does not have a tangible existence in the play, we have a sense

that He has sent two representatives to help the Mother through

her pain. Also, the way the Player relates to the Mother recalls

how the Preacher urges his followers to strip their souls down

to their most essential being. It is the Player who calls her

“Mother,” and when she objects that she is more than

just a mother, he violently disagrees: “That’s all

you are –- Mother,” in a tone of voice that

brooks no argument. His statement is not meant to be derogatory;

while harsh, it is intended to remind her of her most important

function, and hopefully remind her that it is not just an identity,

but also a calling. Also, in refusing to recognize her by name,

the Player maintains a certain distance, like a surgeon or an

undertaker, as if it were unseemly for him to get involved in

the specifics of her life. She, in return, calls him only “Sir.”

The

Mother’s dialogues with the Player are interspersed with

her solo musings and conversations with her son, as well as the

team’s conflicts as they stumble through a losing season.

These dialogues are central and, interestingly, they mirror her

spiritual experience with the Preacher. In their first spoken

exchange, the Player tells her, “I got your call, Mother,”

and we are reminded of the way the Preacher came to her in a moment

of need, alone in a scary, smoked-out stupor. As the Mother said

earlier, God comes to you when you’re alone, and while God

does not have a tangible existence in the play, we have a sense

that He has sent two representatives to help the Mother through

her pain. Also, the way the Player relates to the Mother recalls

how the Preacher urges his followers to strip their souls down

to their most essential being. It is the Player who calls her

“Mother,” and when she objects that she is more than

just a mother, he violently disagrees: “That’s all

you are –- Mother,” in a tone of voice that

brooks no argument. His statement is not meant to be derogatory;

while harsh, it is intended to remind her of her most important

function, and hopefully remind her that it is not just an identity,

but also a calling. Also, in refusing to recognize her by name,

the Player maintains a certain distance, like a surgeon or an

undertaker, as if it were unseemly for him to get involved in

the specifics of her life. She, in return, calls him only “Sir.”

There is another important, if subtle, link between the Player

and the Preacher. The Player, whose spirituality is evident in

his exchanges with the Mother, will not join in the brief prayer

that his teammates share before their games. On several occasions,

he declines even to stand with them, despite their pleas and occasional

harassment. Yet he humbly gets down on his knees with the Mother

to pray for her. Similarly, the Preacher has foresworn all organized

religious activity. “I do not trust myself to that Church,”

he intones, speaking of the place where some congregants pay attention

to clothes, jewels, and cars. Both men are deeply spiritual, but

they call out to God only when in the presence of those whose

souls call out to them.

That both the Preacher and the Player are tall, lean black men

helps to bring out the similarities in their functions for the

Mother, while creating interesting questions about why African-American

cultural and religious values speak so strongly to her -–

a secular Jewish woman who believes in God, but only because it

“takes too much energy not to.” This cultural contrast

is highlighted by the Mother’s discussions with the Player

on Jewish attitudes and practices, and by his snide questions

and comments about Jewish racism. He takes note of the way certain

Jewish people mumble “schvartze” (pronounced “Sh’vah-tzah”)

under their breath when a black person walks by -– he knows

that the word must be the equivalent of “nigger.”

As the Mother defends her culture -– noting how everything

sounds derogatory in Yiddish –- the Player insists on the

destructiveness of these attitudes. Yet, just as his reduction

of her character to “Mother” was not sexist, these

comments manage to skim the surface of anti-Semitism. In fact,

they effectively underscore how faith, whether religious or secular,

depends upon a basic respect for the self and others. In addition,

as two of society’s most noticeable “others”

-– and as two peoples acutely aware of having been slaves

in former generations – Jews and blacks have a great deal

of common ground that can unify them in spite of cultural differences.

These associations provide texture for the relationship that develops

between the Mother and the Player, and also provide opportunities

for the Player to share some of his own personal history and identity:

his childhood poverty, his intense focus on “learning [his]

game” as he grew up, his children that he never sees.

This fascinating exploration is conducted through the Player’s

efforts to instill the Mother with the will to seize control of

her life in spite of her illness. In offering her a life perspective

so vastly different from her own, he attempts to help her find

a true appreciation of the time that she has already spent on

earth, which will liberate her to make the most of the remaining

days -– however many or few they may be. This is where the

title of the piece comes into play. Three Seconds in the Key

refers to the amount of time that a basketball player is permitted

to stand near the net waiting for a pass. The Mother at one point

asks the Player, “How do you take a shot when you’re

so worried about where you stand?” He answers, “Three

seconds is a long time, Mother, a long time. You know when you’ve

had your three seconds in the key, and you just dance in and out.”

The Player’s frequent hostility seems designed to provoke

the Mother to fight back, and hence rediscover and rebuild her

forgotten strength. In a climactic moment, as he’s pushing

her to rise above her pain and exhaustion, they engage in a battle

of wills underneath the scoreboard. Both fall back on racial and

ethnic bigotry in expressing their anger, but as they volley insults

back and forth, with ten-second countdowns for each on the scoreboard,

the conflict becomes a confrontational debate about the Mother’s

weakness of spirit. “I’m fighting for your life,”

cries the Player, “and you’re barely raising your

arm! Use your body, Mother! Use your arm! Arms up on ‘D,’

Mother!” (“D” stands for “defense.”)

This emotional shock treatment ultimately penetrates the Mother’s

self-destructive defenses, and in the end she achieves a peaceful

resignation that frees her to dance in and out of the key with

each three-second moment that is allotted to her by the divine

Scorekeeper.

A few minor structural problems disrupt

the flow of the play at times. For example, the son's presence

is not completely integrated, and the Mother's other immediate

family members -- a husband and a daughter -- are casually mentioned

but never appear in the play and serve no dramatic purpose. According

to an interview with the playwright, the addition of the son was

one of the last changes to the piece. Further, the intense chemistry

between the Mother and the Player was sabotaged towards the end

when their relationship awkwardly developed romantic and sexual

overtones. In the New Georges's production, melodramatic staging

and performances in the last scene between the Mother and the

Player contributed to this awkwardness, which somewhat undermined

the momentum that had been building. Thankfully, these were trivial

fouls that did not significantly detract from our experience of

the drama. Perhaps they even heightened it by exposing the raw

humanity of the theatrical player who created the whole game and

provided us with three very worthwhile seconds in the key.