Coming of Age: Mamet at Sixty

By Robert Vorlicky

This was a big birthday year for David Mamet.

At sixty, he is as productive as he ever has been. He's writing

essays, giving many interviews, maintaining a blog promoting his

new Broadway play November, speaking about his new book

of cartoons Tested on Orphans, writing commercials for

the Ford Motor Company, writing for the popular TV military series

The Unit, enjoying the critically positive reception

of his new movie Redbelt, which he wrote and directed,

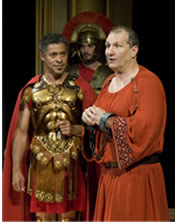

and glowing in the rave reviews of Keep Your Pantheon

(a world premiere now playing at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles

on a double bill with an earlier male-cast play, Duck Variations).

In the press, there's a lot of talk about what Mamet's up to in

2008. He's hot news again, and he appears to be basking in the

attention. He has now moved into a rarified group of "semi-elders"

among American artists, becoming a living cultural torch-bearer.

All in Mamet-land is not rosy celebration,

though. Some think he lost his mind shortly after turning sixty

this past November 30. On March 12, 2008, Mamet published an essay

in The Village Voice entitled "Why I Am No Longer a 'Brain-Dead

Liberal.'" In New York academic circles, actor-training studios

and theater blogs, the essay caused an immediate stir. Nearly

all the participants at the Third International David Mamet Conference

in Brussels, Belgium, which I attended in April 2008, were keenly

familiar with it. Mamet's opinions, it seems, travel very fast.

Toward the opening of the essay, Mamet

prominently mentions his political satire November, the

title of which captures the culmination of the election season

in the United States, in addition to being the month of Mamet's

birth. November is now nearing the end of a critically

mixed run at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on Broadway. The show,

directed by Joe Mantello and starring the comic legend Nathan

Lane, opened on January 17, 2008. A surprise to many--when one

considers its sterling theatrical pedigree in author, director,

and star lead--November closes on July 13, having been

nominated for only one 2008 Tony Award. November is Mamet's

first world premiere on Broadway in his long and distinguished

career. As he remarked to Campbell Robertson in May 2007, "It

just seemed to be a Broadway play."

November has been praised as a

comedy "destined to become a classic" (Christopher Byrne) as well

as belittled and diminished as a "sitcom," an "attenuated sketch"

(Adam Feldman), "a wasted opportunity" (Jennifer Vanasco), and

(along with Caryl Churchill's male-cast Drunk Enough to Say

I Love You?) a "migraine inducing play" (Charles Isherwood

in the New York Times, who also called it the "most irritating

play of the season"). "My play," Mamet writes in his now infamous

essay,

turned out to be about politics, which

is to say, about the polemic between persons of two opposing

views. The argument in my play is between a president who is

self-interested, corrupt, suborned, and realistic, and his leftish,

lesbian, utopian-socialist speechwriter. The play, while being

a laugh a minute, is, when it's at home, a disputation between

reason and faith, or perhaps between the conservative (or tragic)

view and the liberal (or perfectionist) view. . . . I took the

liberal view for many decades, but I believe I have changed

my mind.

While Mamet may have "changed his mind,"

his reasoning in the essay is uneven and reactionary--even for

an often scrupulous debater like Mamet. This is not to say that

the man can't say exactly what's on his mind and own it as his

personal "truth," but his most recent work for the stage does

not wholly reflect his alleged retreat to the ancient binarism

of "reason/faith," "tragedy/perfectionism." Even his pairings

(reason and the tragic versus faith and the perfectionist) are

deceptively rigid and at odds with one another. Mamet's conscious

effort to reason his position in the world--also common in his

other essays and prose works--reminded me, here, of Arthur Miller.

Miller's theorizing about his works never quite matched what his

plays were doing. The theorizing often fell short of the works'

depth and breadth.

But

unlike Miller, who would refer specifically to his plays, Mamet

does not explicitly apply his new political thinking to November.

The essay works as an implied context within which to

think about this play, and also to reconsider his complete canon.

If the reader decides to map Mamet's thinking in March 2008 onto

November, then so be it. The trouble is, such thinking

would align the author's allegiance with his character President

Smith, the corrupt executive running for a second term. Mamet

goes to some length in his essay to demonstrate the similiarities

between a former hero of his, John F. Kennedy, and George W. Bush;

in Mamet's new view, the liberal martyred President and the maligned,

currently seated conservative President mesh as one. This may

indeed be where Mamet's political thinking is now located. He

identifies President Smith as "realistic," a characteristic that

he has long admired.

But

unlike Miller, who would refer specifically to his plays, Mamet

does not explicitly apply his new political thinking to November.

The essay works as an implied context within which to

think about this play, and also to reconsider his complete canon.

If the reader decides to map Mamet's thinking in March 2008 onto

November, then so be it. The trouble is, such thinking

would align the author's allegiance with his character President

Smith, the corrupt executive running for a second term. Mamet

goes to some length in his essay to demonstrate the similiarities

between a former hero of his, John F. Kennedy, and George W. Bush;

in Mamet's new view, the liberal martyred President and the maligned,

currently seated conservative President mesh as one. This may

indeed be where Mamet's political thinking is now located. He

identifies President Smith as "realistic," a characteristic that

he has long admired.

At times, while reading "Why I Am No Longer

a 'Brain-Dead Liberal,'" I wondered if Mamet's pseudo-polemics,

his "eye opening" confession were a bit of a "con" -- a beautifully

crafted piece that challenged the reader to think for herself

or himself. In this way, Mamet challenged us to think about our

relationship to the public realm of politics and its impact on

our private lives. But Mamet was speaking from a different subject

position -- now, as an allegedly converted right-winger, he challenged

his former left-wing brethren to see the error of their ways.

In interviews surrounding his 1976 play

American Buffalo, Mamet spoke ruefully of the "tragic"

demise of the power of the conventional hero, the heterosexual

white male. He saw an evacuation of meaning and value for this

otherwise traditional protagonist. Now, in 2008, he elevated this

figure to the Presidency. Even if Charles Smith's efforts to hold

onto power appear unlikely, there is every reason, the play suggests,

that another, very similar man will fill his shoes. The fraternity

that holds the balance of power appears to remain intact.

If the reader of his essay espouses liberal

politics, Mamet suggests, then she or he needs to confront the

degree to which this position is fraught with contradictions.

At sixty, Mamet finds himself defining liberalism, or the "synthesis

of this worldview," as a politics of "everything is always wrong."

Clarice Bernstein, the liberal lesbian speech-writer in November,

sees the world this way, and her view, the playwright implies,

is exactly why today's liberal is "brain dead." Clarice's sort

of "brain deadness" is what Mamet now claims to have escaped.

However, clever Clarice is really not brain

dead. In fact, her brain is alive and well; it guides her in being

actively successful in getting what she wants. Her world is not

as black and white as Mamet theorizes. Against all odds--that

is, against the playwright's conception of the rigid polarization

he claims to have created in November--she materializes

her "utopic" vision and thereby makes it real. She outsmarts the

man in power and gets power, forcing him to officiate at her legal

wedding to her lesbian partner.

This is what happens in the play, but the

playwright argues otherwise in his Village Voice essay.

The play and the essay are at odds. It's as if the genres of dramatic

writing and the personal essay clash at this moment in Mamet's

hands: the visibility of Clarice in the play versus the presence

(or visibility) of Mamet in the essay (which renders Clarice invisible).

In order to claim the death of liberalism for himself, Mamet--at

least in his essay--erases the success of his liberal character

in November. The play doesn't support the theory of his

fall from liberal political sympathies after forty years.

How did Mamet arrive at his newly revealed

conservative altar? He noted that "a brief review" of his life

revealed that "everything was not always wrong, and neither was

nor is always wrong in the community in which I live, or in my

country. Further, it was not always wrong in previous communities

in which I lived, and among the various and mobile classes of

which I was at various times a part." Mamet acknowledged that

for the past forty years, his work had been both prompted and

informed by a belief that "people are basically good at heart."

As of March 2008, however, he no longer

believed this. He argues in his essay that he does not think that

people are basically good at heart. In fact, he thinks "that people,

in circumstances of stress, can behave like swine, and that this,

indeed, is not only a fit subject, but the only subject of drama."

Turkeys figure prominently in November, written when

Mamet was in his late fifties, yet at sixty he appears preoccupied

by pigs. Albee got into goats in his seventies, so perhaps we

have much to look forward to here.

In November, President Charles

Smith is on the verge of a resounding, humiliating defeat in his

re-election campaign. "Why is everyone turning on me," Smith asks

his personal lawyer and confidant, Archer Brown, to which Brown

responds, "Because you've fucked up everything you've touched."

Confined to the Oval Office, Smith is scheming with Brown about

how to finance his Presidential library. The method they hatch

is to blackmail a lobbyist for the National Association of Turkey

By-Products Manufacturers. How? "Convince a Native American chief

to say that the Pilgrims ate codfish instead of turkey on Thanksgiving--and

called it tuna by accident." Indeed, President Smith is a "swine"

among turkeys, as he flings the "F" word around the stage, offending

nearly every "ethnic, religious, and racial group on the planet."

One-liners proliferate as the play is dominated by Smith's stand-up,

Borcht-Belt comedic turns laced with profanity and slurs.

The twist comes with the arrival of Clarice,

his Jewish lesbian speechwriter, who, plagued with a bad case

of the flu, has just returned with her partner from adopting a

baby in China. As only one critic has noted (Jennifer Vanasco),

Clarice grounds the play--even though, as Michael Feingold notes,

the play is a "cartoon analogue for presidential corruption."

November is no Wag the Dog, as Linda Winer observes,

calling that film the "most prescient piece of politically subversive

comedy to ever make it to the screen." Yet, grounding--that is,

the creation of meaning within its own idiom and on its own terms--even

exists in Mamet's farce, and this is what I think most critics

are missing in November. I also believe it's something

that Mamet himself fails to acknowledge in his own creation. What

does it mean to come out as a newly baptized conservative when

your latest works are empowering a liberal agenda of gay and lesbian

rights? And what does it mean that Mamet placed gays and lesbians

center stage -- and in a much less negative light than in his

pre-conversion days -- at a time when he was also undergoing a

much-publicized return to Judaism, the faith of his childhood?

Clarice's words and actions challenge

the assumed authority in this otherwise male-cast play, a familiar

Mametian world of men among men. The dynamic recalls Mamet's earlier

Speed-the-Plow (1988). But Clarice's challenge is significant

and, to quote Linda Loman, "attention must be paid" to its outcome.

The similarities between Mamet's Jewish lesbian Mom (Clarice)

and Miller's Jewish heterosexual Mom (Linda) are striking.

Moments before the end of Act I (which

occurs in the morning), President Smith and Bernstein have this

exchange, after Smith realizes that his legacy will die the upcoming

Tuesday when he fails to be reelected President of the United

States:

Smith: A harsh world, Bernstein, is it

not…?

Bernstein (waking up): Sir…

Smith: Harsh world. Especially for YOU.

Bernstein: For me?

Smith: As you are a lesbian.

Bernstein: In essence, yes.

Smith: Thus, your day, must abound with constant horrendous

disappointments, insults and betrayals.

Bernstein: I endeavor, Sir, to live my life with self respect.

Smith: That's laudable, Bernstein. It's more than laudable,

it's saintly.

Bernstein: Thank you, sir.

Smith: In spite of your loathsome, and abominable practices.

For, Bernstein, you have been a good friend to me.

Bernstein: Thank you, sir.

Smith: A good friend to a failure. Yes. A man, who looks back.

On his life. What does he see? But missteps, squandered opportunities,

betrayal…loss.

Bernstein: I'm sorry for your troubles, Sir.

This is all that Bernstein gives her employer

throughout the play: she recognizes and acknowledges the truth

of his personal failures. While she is a loyal employee, she neither

hides that she is a lesbian nor writes speeches that betray her

belief in equal rights for all Americans. She simply refuses to

act in a self-betraying manner. Liberal, yes. Effective, yes.

It is not beyond her to "repeat and revise" history, as Suzan-Lori

Parks does, in order to give the President what he needs. Yet

no one suffers from her brainstormings except the President.

Smith: You're what I love about this

country.

Bernstein: I am sir?

Smith: You bet. I know what you would like, is to take over

the government of the United States by force, promoting your

vision of a godless, stateless paradise of homosexuality….is

that correct….?

Bernstein: Essentially.

Clarice still gets what she wants by using

her gift of language--her ability to write moving speeches--as

a bargaining chip. She refuses to write until she gets what she

wants from the President, which is for him to officiate at her

same-sex marriage.

Smith: I like you, Bernstein.

You know why? You're great at what you do. Do I respect you?

Fuck no. Why? Your head is full of trash. But you can sling

the shit. I'll pay you for that. I will pay you for that speech--What

do you want?

Bernstein: I want to marry my partner.

Smith: I can't do that.

Bernstein: Yes, you can.

Smith: It's against the law.

Bernstein: Figure it out.

Smith: Write me my speech.

Bernstein: You figure it out, I'll write your speech. Hands

him a speech.

Smith: ….This is my concession speech. …. I want the

other speech.

Bernstein: I told you my terms.

Smith: I cannot do what you ask. It's illegal.

Bernstein: There is a higher law.

Smith: Oh, bullshit.

Bernstein: There is a higher law.

Smith: What's it called, if you're so smart.

Bernstein: It is the law of love.

Smith: Oh, that's a law? Where is that law written? On your

Chinese amulet? . . .

Bernstein: Mr. President.

Smith: I cannot marry you to a girl. It. Is. Illegal.

Bernstein: Did you ever have a homosexual experience?

Smith: I'm not telling. (pause)

The

latter half of the play is dominated by President Smith's efforts

to coerce Clarice to "craft a speech that will turn around his

sagging poll numbers," or at the very least, initiate the rhetoric

of a plausible legacy. Smith has no support from his party, no

cash, and his poll numbers are in single digits. To this, Bernstein

again appeals to the President "to do something pure. . . . To

marry. Two people who love each other."

The

latter half of the play is dominated by President Smith's efforts

to coerce Clarice to "craft a speech that will turn around his

sagging poll numbers," or at the very least, initiate the rhetoric

of a plausible legacy. Smith has no support from his party, no

cash, and his poll numbers are in single digits. To this, Bernstein

again appeals to the President "to do something pure. . . . To

marry. Two people who love each other."

Smith: It's not legal.

Bernstein: You could make it legal.

Smith: At what cost, Bernstein? Riots? Backlash? We

don't know… . . .

Bernstein: We aren't a "nation divided," Sir. We're

a democracy--we hold different opinions. . . . I'm not at all

sure that we don't love each other. (pause)

Smith: This is a great speech, Bernstein.

In the final act, the morning after the

play opens, Bernstein, dressed in a wedding gown in the Oval Office,

hands over the rest of the speech that Smith will deliver before

a national television audience. The President profusely thanks

her--the speech will be "my legacy," Smith beams. He agrees to

do anything she says and wants, while Brown, the Chief of Staff,

continues to question why Bernstein is in a wedding dress. Bernstein,

however, holds the final word: the speech isn't completed -- and

the President will not see it until after Bernstein and

her lover are married.

Bernstein: We thought, you'd marry us

on TV first, and, then, I'd give you your speech. (pause)

Smith: Don't you trust me, Bernstein?

Bernstein: Sir? I don't trust anyone. But, if I did?

I'd trust you first.

Archer reminds the President that it is

illegal for him to marry a same-sex couple:

Smith: What is legal? Is it

"legal" for the State to deny two perfectly good citizens, the

right to "get married," just because they're both girls?

Archer: ….yes.

Smith: Well, that's a crime…

Archer: Yeah, it's a damn shame.

Smith: It allows, uh, uh, uh, "other" people to get married.

Archer: That it does.

Smith: At one time. It prohibited. . . . . uh, uh, uh people

of other races from marrying ….. it prohibited people of other

races, from marrying people of other races.

Archer: It ain't going to fly . . .

Smith: No, they have rights, just like regular human beings.

In a smart, thoughtful on-line review in

"AfterEllen.com," an off-the-mainstream-radar lesbian blog, critic

Jennifer Vanasco wrote several days after the play's opening that

"the most astonishing thing about David Mamet's new, manic Broadway

play," is its "lesbian hero." As Vanasco rightly concludes:

Bernstein is a lesbian revolutionary

working for a president who is a racist, misogynist, homophobic

extortionist. And yet before the play is over, Clarice will

endanger her life, stick to her ideals, and work hard to convince

the incumbent President that he should officiate at her and

her partner's wedding on national television, thus setting a

precedent for gay and lesbian couples throughout the United

States. . . . It is Clarice who changes his mind. Sort of. Well,

OK, it's not ever clear that she changes his mind, but she at

least writes a speech that he is desperate to give, and in that

speech she talks about how it is exactly this play of difference

upon difference that makes America strong, especially when it

is tempered by the liberal idea that despite these very differences,

we should respect (and maybe even have affection for) each other

anyway.

In the New York production, Clarice, decked

out, awkwardly, in her fluffy wedding dress, hands over her speech

to the president and makes it very clear what she expects him

to do. She has already explained to the press that Smith is going

to marry her at the beginning of the telecast. In the meantime,

the Chief of Staff has convinced Smith that he can marry the women,

but that the TV cameras will be turned off. This counterplot is

foiled, however, as Clarice overhears the plan. The spectator

has every reason to believe that if President Smith goes back

on his promise to Clarice, the lesbian speechwriter, her partner,

and the baby would still find their way to the national screen.

Clarice is not without the balls of Mamet's men. She is a voice

of idealism, but idealism wedded to action, as she cuts and negotiates

deals on her own in order to advance her agenda of equal rights.

She insists that her liberal politics see the light of day. She's

committed to seeing that her ideals are enacted -- that they become

a part of the "real."

Moments before the play ends, the President

seems to waiver as to whether or not he'll marry the lesbian couple.

Clarice hands over the speech and she is accused of having brought

bird flu with her from China, which will infect the U.S. population.

She is intimidated, but is she also selling out? We don't know

for certain, since neither the president nor the spectator knows

exactly what the content is of the text she has given

to him. It may well be bogus. Just as those in the Oval Office

are about to make their way to the TV cameras, a Native American,

Dwight Grackle, barges into the room, demanding the return of

stolen lands. He shoots a poisoned blow-dart at President Smith

as Bernstein "interposes herself between the assassin and the

President." The president is deeply moved as he gazes at the lesbian's

"dead" body: "She took a poison dart for me….She gave up her life

for her country."

But then, like the phoenix, Bernstein rises.

"How has the white woman survived," asks the Native American,

"the poison has never failed." "I think the dart struck my amulet,"

responds the speechwriter. "You risked your life for me, why?"

asks the president.

Bernstein: Sir, you're the President.

The people voted for you.

Smith: They were mistaken.

Bernstein: That's their right.

Smith: Bernstein, you know who I am--I'm just some

guy in a suit.

Bernstein: Sir, with respect? So were all the other guys who

sat here.

Smith: What? George Washington ?

Bernstein: Guy-in-a-suit.

Smith: Abraham Lincoln?

Bernstein: Guy in a suit.

Smith: Bernstein, Lincoln freed the slaves. I can't free the

slaves.

Bernstein: You could marry me and my partner. (pause) It would

be your legacy. . . .

Smith: Bernstein -- wash your face -- you're getting married.

Archer: It'll cost you the election.

Smith: Damn job's a pain in the ass. Too much stress. . .

Bernstein. Come on. I'm giving you away. . . . Jesus

I love this country.

In what many might see as an unexpected

ending to a play by David Mamet, the lesbian couple get their

wish at the end of November--they are to be married by

a sitting President of the United States, a federally sanctioned

acknowledgement of their right to be legally married and recognized

as a family, with their adopted child. This staged utopian vision

of legality has contemporary resonances offstage, most recently

in the California Supreme Court's ruling on May 15, 2008 that

permitted same-sex marriage in the state to begin on June 16.

This fact, however, is glaringly absent in nearly all of the criticism

to date on the play.

Critics were equally blind to, if not dismissive

of, any redeeming gay relationships in Mamet's last play, Romance,

which premiered on March 1, 2005 at the Atlantic Theater Company.

Nearly all saw this slapstick courtroom farce as a schizophrenic

romp of out and closeted gay characters whose behaviors skewered

the U.S. judicial system. As Caryn James wrote, the play "seemed

so out of touch with its moment. . . . it was a sometimes-clever

misfire that strained to be outrageous." Yet, very few critics

noted that Mamet actually presented a romance in the male-cast

Romance. The characterizations were admittedly trite,

but Mamet put front and center his first believable gay male couple,

the Prosecutor and his young lover Bernard. I certainly don't

want to overstate the significance of this relationship, or idealize

or romanticize it. Its value is in the fact that it was there.

When one considers how he has presented

gays and lesbians in past works, Mamet has come a long way. We

might recall: Robert's repressed "ephemeris" (a kind of "don't

ask, don't tell") sexual feelings toward John in A Life in

the Theatre (1977); the sado-masochistic relationship between

Edmond and his dominating cellmate lover in Edmond (1982);

the profound alienation between John and his younger lover, Charles

in The Shawl (1985); and the self-loathing homosexual

Del in The Cryptogram (1994). In Boston Marriage

(1999), Mamet's first female-cast play, which was also his first

effort to narrow and sustain his focus on the dynamics of homosexualities,

he set his historical drama of lesbian desires, secrets, and lies

in the late 19th century. It's as though the distance from the

contemporary period eased him into a world he could only imagine--the

public constraint and the private liberties of the Victorian era

provided him with the dramatic space to be a voyeur into his sexual

and gendered "other." But from another perspective, as Ira Nadel

points out in his recent Mamet biography, "what is the impact

of Hollywood on [Mamet's] dramatic work? Does it explain why genres

begin to dominate his writing, satire for example controlling

Boston Marriage, farce governing Romance?" Interestingly,

the plays Nadel cites are those dominated by lesbian and gay characters--and

their genres are satire and farce.

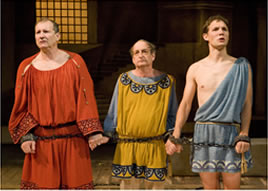

I

see Romance as the first play in Mamet's historically

noteworthy, albeit modest, "gay" comedic trilogy (which also coincides

with the period following his (re)conversion to Judaism)--the

other two plays being November and the one-act Keep

Your Pantheon, or On the Whole I Would Rather Be in Mesopotamia

(which first aired on BBC Radio 4 in May 2007 before its stage

premiere at the Mark Taper). As Sean Mitchell wrote in the Los

Angeles Times, the play's three main characters are out-of-work

actors led by Strabo, a middle-aged "gay wannabe star" whose "jealousy

of another (possibly better) acting troupe drives him to distraction

while desperately scheming to escape a death sentence issued by

the emperor (and drama critic) Julius Caesar." "Making matters

more vexing," writes Los Angeles Times head critic Charles

McNulty recently in his rave review of the play, is Strabo's "hankering

to bed rosy-face Philius," a twenty-something, apprentice actor

and boy-toy, who thinks Strabo is "disgusting but is set on becoming

an actor." As in Romance, homosocial, homoerotic, and

homosexual relationships abound in Pantheon, and the

boundaries of sexual exchange remain fluid throughout its action.

Out of the sixteen characters in Mamet's last three plays--this

"trilogy"--fifteen are men and one is a lesbian (Clarice). What

I am pointing out is that, since 2005, Mamet has returned to writing

male-cast plays--a choice that characterized many of his prized

earlier works--but unlike in those earlier plays, gay and lesbian

characters are now central figures whose sexuality is far less

problematized.

I

see Romance as the first play in Mamet's historically

noteworthy, albeit modest, "gay" comedic trilogy (which also coincides

with the period following his (re)conversion to Judaism)--the

other two plays being November and the one-act Keep

Your Pantheon, or On the Whole I Would Rather Be in Mesopotamia

(which first aired on BBC Radio 4 in May 2007 before its stage

premiere at the Mark Taper). As Sean Mitchell wrote in the Los

Angeles Times, the play's three main characters are out-of-work

actors led by Strabo, a middle-aged "gay wannabe star" whose "jealousy

of another (possibly better) acting troupe drives him to distraction

while desperately scheming to escape a death sentence issued by

the emperor (and drama critic) Julius Caesar." "Making matters

more vexing," writes Los Angeles Times head critic Charles

McNulty recently in his rave review of the play, is Strabo's "hankering

to bed rosy-face Philius," a twenty-something, apprentice actor

and boy-toy, who thinks Strabo is "disgusting but is set on becoming

an actor." As in Romance, homosocial, homoerotic, and

homosexual relationships abound in Pantheon, and the

boundaries of sexual exchange remain fluid throughout its action.

Out of the sixteen characters in Mamet's last three plays--this

"trilogy"--fifteen are men and one is a lesbian (Clarice). What

I am pointing out is that, since 2005, Mamet has returned to writing

male-cast plays--a choice that characterized many of his prized

earlier works--but unlike in those earlier plays, gay and lesbian

characters are now central figures whose sexuality is far less

problematized.

Eight months before November's

world premiere, Mamet was quoted in the New York Times

and the International Herald Tribune as saying that it

was about "three men in a room trying to work things out"--presumably

he was referring to President Smith, Chief of Staff Brown, and

the representative from the turkey industry. Clarice Bernstein,

who is onstage as much as any other character besides the president,

is rendered invisible in Mamet's remarks. She is not to be counted

as a person who shares space in a room where "three men….are working

it out." This, despite the fact that the sound-bites in May 2007

on posters, bus billboards and radio clips announced November

as a play about "civil marriage, gambling casinos, lesbians, American

Indians, presidential libraries, questionable pardons and campaign

contributions." In this context, lesbians and American Indians

were depleted of their subjectivity, meriting mention only in

a cataloguing of "things." Ah, marketing.

Once

November opened on Broadway to mixed reviews, Caryn James

wrote an expose in the New York Times entitled, "In Mamet's

Political World, the One With Ideals is Odd Woman Out" (February

20, 2008). James wrote that Clarice's efforts "to get the president

to perform a wedding ceremony for her and her partner" -- or the

gay marriage plot -- "seems a tired bid for Oleanna topicality."

James is quick to say that the Chief of Staff, whom she considers

the most vital character on stage, and the audience share the

same cynicism -- they encourage the president to double-cross

Bernstein. But here's where I disagree. First, in James's universalizing

of the spectators' perspective(s). Second, in her failure to acknowledge

that Clarice does get what she wants. The fact that a

lesbian, non-crossdressing marriage plot is nearly realized in

the work of a major American playwright on Broadway is a substantial

leap in U.S. theatrical representation. To see it happen in the

play rather than anticipate its occurrence after the curtain will

be a next step in theatrical history.

Once

November opened on Broadway to mixed reviews, Caryn James

wrote an expose in the New York Times entitled, "In Mamet's

Political World, the One With Ideals is Odd Woman Out" (February

20, 2008). James wrote that Clarice's efforts "to get the president

to perform a wedding ceremony for her and her partner" -- or the

gay marriage plot -- "seems a tired bid for Oleanna topicality."

James is quick to say that the Chief of Staff, whom she considers

the most vital character on stage, and the audience share the

same cynicism -- they encourage the president to double-cross

Bernstein. But here's where I disagree. First, in James's universalizing

of the spectators' perspective(s). Second, in her failure to acknowledge

that Clarice does get what she wants. The fact that a

lesbian, non-crossdressing marriage plot is nearly realized in

the work of a major American playwright on Broadway is a substantial

leap in U.S. theatrical representation. To see it happen in the

play rather than anticipate its occurrence after the curtain will

be a next step in theatrical history.

After Mamet's "Why I Am No Longer a 'Brain-Dead'

Liberal" appeared in the Village Voice, the publication

received a great many letters to the editor (in print and on-line),

continuing for several weeks. Here is a sampling:

"Mamet's pseudo-controversial essay

was about as facile as the author's past decade of writing.

. . Mamet's 'privileged class' status has rendered him both

basic and boring."

"The point Mamet needs to deal with is

when he stopped giving a fuck about anyone else outside his

rarified circle. Or, in the vernacular of his characters: Suck

it, Mamet."

"Thanks to Mamet for writing it, to the

Village Voice for having the courage to publish it,

and to Rush Limbaugh for mentioning it on his radio show."

Following the weekly and blog responses

to Mamet's essay, New York Times theater critic Isherwood

weighed in on April 6, 2008, commenting not only on Mamet's "recently

proclaimed political conversion from liberalism" but also on his

"troublesome" play November. Isherwood comments on "the

play's unconvincing conclusion, which finds the president agreeing

to take the noble step of presiding over the marriage of his speechwriter

and her partner, [which] is like putting a Band-Aid on a bullet

wound." He was disturbed that the "real message of the play is

that it's all right to laugh when people shout insults like 'lesbian

swine.'" As with James's article, I'm uncomfortable with Isherwood's

universalizing of spectators' responses and deducing from this

faulty observation what he believes to be the "real message" of

November. From my seat, a lesbian got what she wanted--and

she did so without compromising her principles. And I wonder why

so many critics find it difficult to grant her this success. Mamet

is the one who stated in his essay:

I think that people, in circumstances

of stress, can behave like swine, and that this, indeed, is

not only a fit subject, but the only subject, of drama.

Rather than vicitimizing Clarice in the

world of the play as a "lesbian swine," spectators have the agency

to consider the source of the insult. After all, Clarice does.

Why shouldn't we? The audience is not powerless. It knows whence

its laughter comes, and it comes from many different bodies. Many

of these laughing bodies know who the swine is on stage.

Many are more than capable of identifying

pigs.

Many also know what they hear and see in

November -- and they are capable of calling it for what

it is.

I say, let's face it. The lesbian wins.

Happy (belated) sixtieth birthday, David

Mamet -- who would have thought you would write what precious

few have called admirable, even "heroic" gay and lesbian characters

at this time in your life? You seem to have arrived at an artistically,

politically and personally liberating--albeit complicated--juncture,

as revealed in the live performances of your most recent, humorous

works.

How utterly conservative of you.