Artifact

as Survivor

Artifact

as Survivor

By Alexis Greene

I Am My Own Wife

By Doug Wright

Playwrights Horizons

416 W. 42nd St.

Box office: (212) 279-4200

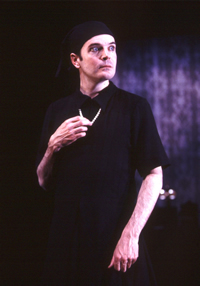

The dark eyes of Jefferson Mays glitter

ferociously as he stands on the main stage at Playwrights’ Horizons.

Costumed in a black peasant dress adorned only with a string of

pearls, he portrays a German transvestite named Charlotte von

Mahlsdorf in Doug Wright’s new play I Am My Own Wife.

Looking at the audience, seeing us see the mesmerizing combination

of graceful actor and piercing expression, Mays challenges us,

if we can, to uncover the secrets of Charlotte’s private world.

This daring, imaginative performance is

the main reason to see Wright’s play, which tries desperately

but unsatisfactorily to reveal a fascinating character to us and

to himself, and to find a metaphor for survival in her unique

story.

Wright, who is probably best known as the

author of Quills, a drama about the Marquis de Sade,

first met Charlotte in 1992, when she was 65 and still living

in Germany, and interviewed her and corresponded with her until

she died in 2002. When Lothar Berfelde was in his early teens,

Wright learned, a cross-dressing aunt helped the boy discover

his true sexual orientation, and Charlotte, a woman with jaw-length

blonde hair and massive hands, emerged. At the age of sixteen,

according to the play, she murdered her abusive Nazi father, who

she believed would have killed her and her mother. Jailed for

the crime, she claims to have escaped when the Russians attacked

Berlin toward the end of World War II and eventually she moved

into a crumbling mansion. There she started collecting Victrolas

and gramophones, late-nineteenth-century clocks and furniture,

which the play suggests she cherished more than human beings.

The Berlin wall went up, and Charlotte

lived in East Berlin in her furniture museum, running a tavern

for gay men and women in the basement and keeping the secret police

at bay, probably by informing on fellow collectors. When will

you marry, her mother asked when Charlotte was around 40. “I am

my own wife,” Charlotte told her.

On stage this story unfolds like a documentary.

It is an amalgam of excerpts from Wright’s taped interviews, recreations

of his own process of self-doubt and partial discovery, and cameos

of people in both Charlotte’s world and his own. Mays acts Charlotte

and at least 40 other characters, almost always wearing the black

dress and pearls but seamlessly changing accents, physical postures

and outlooks. By turns he plays the gentle aunt; an angry jailed

friend who does not know that Charlotte has betrayed him to the

police; an asinine television talk-show host; and most importantly

Doug Wright, anxious, caring interviewer and dramatist. Editor

as much as playwright, Wright constructs a piece that cuts back

and forth between Charlotte and the people she encounters, including

himself, sitting in her museum and recording her words on tape.

The elegant production lends the play the

freedom it needs. Upstage, scenic designer Derek McLane provides

a high wall of shelves stuffed with clocks, tables and vintage

record players, lit by David Lander so that the objects glow with

a sort of burnished shine.

Downstage, the director Moisés Kaufman

puts only an occasional wooden table or cabinet, on which Charlotte

sets a Victrola or, in the production’s artful approach to offering

a tour of her museum, miniature pieces of furniture. Unfortunately

Kaufman paces every sequence similarly, so that the production

feels without rhythmic variation.

But exquisite though the production looks,

and riveting though Mays is, something is lacking in the play.

It is as if Wright became so enveloped by his research that he

lost his way. In an interview with Playwrights artistic director

Tim Sanford, Wright describes how “the more I discovered about

my central character, the more conflicted I became about her very

nature. And it became harder and harder and harder to write.”

Five years after he began to interview Charlotte, he felt blocked

and had not found a dramatic form for his passion.

Ultimately, working with Kaufman and Mays,

Wright evolved the play’s current shape. But sitting in the theatre,

we yearn for more scenes depicting this unique woman, and fewer

showing the writer, no matter how adeptly Mays transforms from

one to the other. While breaking through his own creative wall,

Wright constructs a barrier of interviews and facts between us

and his subject.

Perhaps the barrier is a natural outcome

of the playwright’s frustration. As the character of Wright admits

more than once, he never penetrates to the heart of the intriguing

Charlotte. Never learns what beats beneath the pearls and the

black dress. Nor do we. What was her sexual life? Did she even

have one? According to a 1992 German documentary, she did, but

for some reason Wright excises this vital side of Charlotte’s

personality.

Except for a few moments, largely created

through the gleaming eyes and open face of the extraordinary Mays,

we rarely glimpse this woman’s soul. One glimpse comes when the

teen-age Charlotte, dressing in her aunt’s clothes, first looks

at herself in a mirror, and we see an instant of recognition and

pleasure. Another happens when she describes killing her brutal

father.

But mostly, as Wright voices toward the

play’s end, Charlotte is like a piece of her beloved collection.

“I became this furniture,” she says at one point. In this identification

Wright finds a symbol and an answer to how Charlotte survived

two murderous political regimes. To us she remains a curiosity--fascinating,

but veiled and not quite human.