Animated

Operas

Animated

Operas

By Martin Puchner

Master Peter's Puppet Show

By Manuel de Falla

The Return of Ulysses

By Claudio Monteverdi

(closed)

In the opera, characters come to life through

the singers' voices. That these singers also have bodies and that

these bodies should be capable of acting is often an afterthought,

except when the singers' bodies become so large that they somehow

get in the way. The world-class soprano Deborah Voigt recently

found this out the hard way when she was dropped from a production

at London's Royal Opera because she was deemed too voluminous

to appear in a cocktail dress on stage. But usually, everyone

pretty much accepts that singers aren't held to the same corporeal

and actorly standards as dramatic actors. When once in a while

a singer breaks this rule and displays acting prowess--for example

Lauren Flanigan--a second problem emerges: the opera is revealed

as a stylized and formulaic art form that doesn't call for, or

permit, naturalist acting. What is a good actor to do during those

long repetitions and developments conceived of by the composer

with no consideration for stage action? Stand still until the

next unit of action is finally reached, or else run all over the

stage desperately miming the emotions that are already expressed

by the music?

Recently, New York theatergoers could witness

two instances of a fascinating solution to these problems: the

staging of opera with puppets in Manuel de Falla's Master

Peter's Puppet Show, presented by the Brooklyn Philharmonic

and the Compania Tridente of Granada at BAM, and in Monteverdi's

The Return of Ulysses, presented by the Theatre Royal

de la Monnaie at Lincoln Center. Both these productions separated

the singers from the actors and replaced the onstage performers

with puppets, allowing the singers to concentrate on voice while

the puppets suggested the more abstract and stylized characters

called for by the musical form. The differences between the productions

were striking, however, and they shed interesting light on opera,

puppet theater, and the art of acting.

De Falla's Master Peter's Puppet Show

was part of a concert dedicated to three twentieth-century Spanish

composers interested in Don Quixote: de Falla, his contemporary

Oscar Esplas, and the younger Roberto Gerhard. De Falla is the

most well known and also the most explicitly theatrical of the

three. His wild juxtaposition of vastly different styles, ranging

from Renaissance songs to 18th-century keyboard masters, is reminiscent

of Stravinsky's historical collages, and in theater circles de

Falla is best known for The Three-Cornered Hat, a ballet

written for Diaghilev and presented with sets and costumes designed

by Picasso in 1919.

Of the pieces performed at BAM, only de

Falla's Master Peter's Puppet Show, written between 1919

and 1922, called for and received a stage representation. It is

based on the episode in Don Quixote in which the protagonist

watches a puppet show and gets so drawn into the action that he

seeks to rescue the damsel in distress, only to destroy poor Master

Peter's puppet theater in the process. De Falla conceived of his

piece as a puppet opera: the puppet show itself, but also Don

Quixote, Master Peter, and a Narrator are represented by puppets.

Thus, it contains a puppet show within a puppet show, with some

puppets representing puppets and others representing humans--a

perfect occasion, one might think, to probe the difference between

the world of effigies and the world of humans that Don Quixote

so destructively ignores.

Taking its cue from Cervantes's Baroque

fascination with overlapping levels of reality and fiction, The

Compania Tridente of Granada revels in devising the multiple layers

of puppet theaters. Life-size figures watch Master Peter's show,

which keeps changing from its initial geometrical set into a variety

of other theaters and styles, like so many Russian dolls hidden

inside one another. There is a certain amount of ingenuity in

these transformations. As one puppet stage disappears, for example,

the puppets remain without a frame until their shadows are projected

onto a screen that appears behind them: the puppet show has momentarily

become a shadow theater. On the whole, however, the constant changes--which

seem to have absorbed most of the company's creative energy--are

distracting and contribute little to the episode. All of the interest

is in the transitions from puppet theater to puppet theater, with

each set of puppets barely knowing what to do once its little

theater stands. The puppets remain largely static or else move

aimlessly about in clumsy ways. It is hard enough to convince

opera singers to make an effort at acting. These puppets are worse.

They are neither comic nor tragic, neither crudely jocular nor

eerily uncanny (as puppets often are). They are simply wooden

and don't know what to do on stage. Indeed, they seem to suffer

from stage fright.

Still more disappointing, the singers,

music, and puppets are entirely disconnected from one another.

The singers are removed from the stage and stand in the orchestra

pit. The large puppets of Don Quixote and the Narrator don't know

how to react to the constant set changes occurring in the puppet

theater (and one can't blame them for this, since the changes

are entirely unmotivated), and the Don Quixote puppet doesn't

know what to do when the Narrator laboriously recounts the story

to be shown on the puppet stage. Even the culminating action,

the final destruction of the theater by the misguided Don Quixote,

consists only of a few awkward stabs at the frame. Narration,

orchestral music, arias, outer puppets, and inner puppets all

appear as fragments of a whole destroyed by some willful, misguided

fellow.

These

same ingredients--shadow theater, life-size puppets guided by

multiple puppeteers, and separate singers--are also part of de

la Monnaie's Return of Ulysses, but to an infinitely

more compelling effect. Over many years of productive collaboration,

director William Kentridge and the South African Handspring Puppet

Company explored the profound potential of puppets. Their grotesque

and harrowing adaptation of Alfred Jarry's Ubu Roi, Ubu

and the Truth Commission, set in South Africa before and

after apartheid, was shown to universal acclaim in New York at

the Biannual Puppet Theater Festival in 1998. For The Return

of Ulysses, the group created much more classical and lyrical

puppets. As in Master Peter's Puppet Show, the main protagonists

are each presented by an almost life-size puppet, a puppeteer,

and a singer. But where de Falla's work had kept these performers

separate, here they are carefully integrated. The production did

not just disassemble characters; it also reassembled them. First,

the singers were up on stage, part of the ensemble, and they even

helped to guide the puppets. In addition, the singers' delicate

modulations, especially those of Kristina Hammarström as Penelope

and of Fuiro Zanasi as Ulysses, were picked up by the subtle puppeteers

and by the orchestra, which was placed in a semi-circle on the

stage. All the instrumentalists, manipulators, and singers thus

shared a single space and their finely attuned interactions realized

a multi-layered whole. In de Falla's piece, the result was accidental

fragmentation.

These

same ingredients--shadow theater, life-size puppets guided by

multiple puppeteers, and separate singers--are also part of de

la Monnaie's Return of Ulysses, but to an infinitely

more compelling effect. Over many years of productive collaboration,

director William Kentridge and the South African Handspring Puppet

Company explored the profound potential of puppets. Their grotesque

and harrowing adaptation of Alfred Jarry's Ubu Roi, Ubu

and the Truth Commission, set in South Africa before and

after apartheid, was shown to universal acclaim in New York at

the Biannual Puppet Theater Festival in 1998. For The Return

of Ulysses, the group created much more classical and lyrical

puppets. As in Master Peter's Puppet Show, the main protagonists

are each presented by an almost life-size puppet, a puppeteer,

and a singer. But where de Falla's work had kept these performers

separate, here they are carefully integrated. The production did

not just disassemble characters; it also reassembled them. First,

the singers were up on stage, part of the ensemble, and they even

helped to guide the puppets. In addition, the singers' delicate

modulations, especially those of Kristina Hammarström as Penelope

and of Fuiro Zanasi as Ulysses, were picked up by the subtle puppeteers

and by the orchestra, which was placed in a semi-circle on the

stage. All the instrumentalists, manipulators, and singers thus

shared a single space and their finely attuned interactions realized

a multi-layered whole. In de Falla's piece, the result was accidental

fragmentation.

Kentridge and Adrian Kohler, principal

puppet maker and designer of Handspring, achieved precisely what

de Falla had intended almost a hundred years earlier: a modern,

animated opera. This historical similarity is worth contemplating.

The last turn-of-the-century witnessed a striking resurgence of

serious puppet and marionette theater, including Jarry's Ubu

Roi. Indeed, many of the most significant playwrights, from

Maeterlinck and Yeats to Lorca--all them more or less de Falla's

contemporaries--wrote well-known plays explicitly for puppets,

even though these plays are now usually performed by human actors.

Moreover, many visionaries of the stage, such as Gordon Craig,

called on actors to imitate the impersonal grace of marionettes.

The discontentment with traditional acting and traditional actors

was caused, among other factors, by the newer media, including

film, photography and radio, as they transformed the theatrical

arts. And herein lies the analogy to our own time. We too live

in an era when new media are transforming older art forms, not

just theater but also those, such as film, that had contributed

to the new puppet theater a hundred years ago. The recent success

of Lord of the Rings, acted alternately by humans and

the creations of animation engineers, is perhaps the most visible

result of this development.

From this perspective, The Return of

Ulysses does more than simply avoid the mistakes from which

the recent production of Master Peter's Puppet Show suffers.

It takes the creation of a puppet opera as an occasion for a breathtaking

experiment in contemporary animation. This is perhaps only to

be expected from Kentridge, who is best known for his charcoal-drawn

animated films. Such films found their way into Return of

Ulysses. At times, the drawings develop their own symbolism.

Ulysses, for example, is represented by a single curved line that

turns into a straight line, Ulysses's bow and arrow, with which

he kills the suitors. At other times, the film animation shows

allegorical figures, for example the owl of Minerva--Ulysses's

guardian god--and also stylized landscapes and cityscapes that

look like Manhattan avenues drawn with a Renaissance fascination

for central perspectives. Repeatedly we see a richly adorned Renaissance

proscenium stage that can turn quickly into the silhouette of

Ulysses's boat in the style of a shadow theater.

One of the most compelling moments occurs

when the film animation creates a bare landscape before which

the puppets can walk and move. What is truly stunning about these

scenes and the company's work with puppets in general is that

the puppets really move and gesticulate like humans. This does

not mean that they seek to fool us into thinking that they are

real, as if hoping for a Don Quixote to mistake them for people.

But it does mean that they have shed all the clumsiness often

associated with more amateurish forms of puppet theater. Once

more, Kentridge succeeds where the Compania Tridente of Granada

had failed, namely in creating a multiplicity of transformations

in which different animated figures and forms interact and counteract

one another.

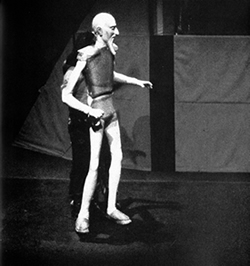

The opera opens with Ulysses sleeping on

a table half covered by a blanket, surrounded by gods. Ulysses

is a puppet---but a puppet that breaths. This is the mysterious

core of all serious puppet theater: the attempt to animate dead

matter. The sleeping Ulysses puppet remains the animating center

for the conceit on which the entire show is based. His return

is simply too good to be true; in fact, it can only be the product

of wishful thinking. All the events depicted in the opera--Ulysses's

return, his recognition by the swineherd, the alteration of his

appearance by Minerva, Penelope's fidelity and the final revenge

on the suitors--are the products of his dreaming as he lies on

some foreign shore, an old man who will never return home. The

dreaming--and breathing--Ulysses is the heart of the action that

takes place around him.

This breathing and dreaming Ulysses thus

animates the production, but is at the same time an animating

principle that is ruthlessly analyzed, tested, taken apart, and

destroyed. For Ulysses is lying on a kind of operating table and

the cruel gods that surround him, played by puppeteers and singers,

actually operate on him for their sport. This production is interested

in animation as a subject of anatomical analysis.

The desire for anatomical knowledge is

picked up in Kentridge's animated films, which frequently depict

anatomical drawings, even close-ups of surgical cuts and operations,

but also drawings of the pulsing heart. They are reminiscent of

the anatomical drawings that had become current in the decades

before Monteverdi's work, for example those of Leonardo da Vinci;

but their rough, charcoal quality also has something of Goya's

dark dismemberments. It is here that the production reveals the

violence that forms the undercurrent of animation. As much as

we want to bring puppets to life, we also want to destroy them,

cutting them up in order to see that the living body is nothing

more than a dead mechanism. Animation is but the counterpart of

destruction. This is, perhaps, why so much puppet theater is infused

with violence, especially in its lowest forms such as Punch and

Judy. Kentridge understands the fundamental relation between animation

and destruction, and his genius lies in the ability to find ever

new forms to illuminate it: live singers and dead puppets forming

single characters; breathing puppets; anatomical animation. All

this is part of the dream-life of puppets and also, perhaps, of

the human puppeteer.

The table on which Ulysses lies is an operating

theater, a theater in which each of his limbs and reactions is

exposed to the onlookers, who are anatomists and audience members

at the same time. The gods' analytical violence is ultimately

our own. We too watch Ulysses, we too are interested in his reaction

and his emotions, and we too are eager to see how fast his heart

beats when he sees the suitors or when Penelope finally recognizes

and acknowledges him. People in the theaters get angry when something

is obscured from their view. Here we are reminded that all theaters,

ultimately, are operating theaters where protagonists are taken

apart for our viewing pleasure. In this case, the anatomy lesson

we get is not so much a moralistic denunciation of voyeurism as

it is one more way of raising the question of life and death.

It is a tribute to how deeply this production understands the

magic and violence of puppet theater that we walk away realizing

that this magic and violence have been part of theater all along.

print version

print version