HOTREVIEW.ORG - Hunter On-line Theater Review

Producing Classical Drama in the United States

By Arnold Aronson

[Editorial note: The following essay was written in 2005 for a conference in Weimar called “Spieltrieb” (the urge to play), organized on the centennial of Schiller’s death. The conference invited a wide array of distinguished international speakers to consider contemporary problems of producing classical drama. Arnold Aronson’s essay, the only American scholarly contribution, appeared in German translation in the valuable volume of conference proceedings Spieltrieb. Was bringt die Klassik auf die Bühne edited by Felix Ensslin (Theater der Zeit, 2006), but it was never published at the time in English. As the original text recently became available to HotReview, we post it now on the thought that its concerns are still very relevant and should be accessible to readers with no German.]

. . . sweet smiling Memory, goddess of the past . . .

--Schiller, The Robbers 2.1Hamlet, pondering the relationship between the Player and a character being enacted, asks the famous question: “What's Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba?” [II.ii.558] Hamlet’s question is really about the psychology of acting, but it might as well be about the place of so-called classics within contemporary culture. Hamlet never doubts the relevance of the classical text. For Hamlet, that is, for Shakespeare, there was a direct connection from antiquity to the living present. The past was a mirror in which the Elizabethans could see themselves. The same might be said for the Greeks who also re-imagined, re-enacted, and re-presented ancient myths. But, in looking at the place of classical drama in the early 21st century, we might well paraphrase Hamlet’s question. What is Hamlet to us? Or Phèdre. Or Mary Stuart or Faust?

The question becomes more acute if asked in the context of American theatre and society. None of the dramas that are designated as classical partake of American history, literature, mythology or, arguably, sensibility. If I, as an American, ask, “What is Hecuba to me?” the inevitable answer must be, “Nothing.” I would contend that the United States is a country with no history. Unlike the later European revolutions that aimed to remake society through the substitution of one form of government for another, the American revolution—or at least the narrative that was created in its wake—sought a rupture with the past. The post-Renaissance European heritage, and thus the classical foundation of the Renaissance, was rejected. The American mythos suggests a new society invented from the raw materials of the “new world,” untainted by the corruption of old. The history of American culture down to the present can be seen as an ongoing struggle between an embrasure and rejection of European forms. But because those who would reject the past were and are ineluctably tied to it, the American cultural narrative is confused—made up of a pastiche of borrowings from other, usually older, societies. Except for the Native Americans who were eliminated or marginalized, we are a country of immigrants. We have no ancient myths except for those of the homes of our ancestors; we have no connection to the land beyond a few hundred years at best and much less for most people; and we are a country that constantly reinvents itself, thereby creating a sensibility in which history is simply that which is older than we are. The repertoire of American theatres seems to reinforce this lack of connectedness, lack of past, lack of historical sensibility. The origins of the American nation produced no lasting drama.

Let me begin with a few startling statistics. A survey of American institutional theatre over the past 10 years reveals an amazing lack of “classical” theatre except for Shakespeare, the occasional Greek, and the odd Molière here and there. There are approximately 400 “not-for-profit” theatres in the United States—theatres supported in large part by state, corporate and philanthropic funding. These range from very small, community-based operations, to large-scale institutional theatres that comprise the “regional theatre” circuit and exist in most major cities, and it also includes many of the companies that constitute “off Broadway.” (Of these 400, no more than perhaps 30 might be considered significant cultural entities.) These theatres exist in opposition to the commercial theatres—primarily the Broadway theatres of New York City—that produce entertainments with the intent of generating a profit. Most of the serious, literary theatre, certainly most of the classical theatre production in the US, is generated by the not-for-profit theatres. Over the past 10 seasons, among these 400 theatres, there have been 540 productions of Shakespeare, 26 productions of Greek tragedy (but not a single comedy), and a rather surprising 43 productions of a select few Molière plays.* But these are the authors and plays whom any reasonably educated American might have encountered in a university drama class. Almost anyone with any cultural knowledge will have a passing familiarity with these names and a few of the plays. Who does not know Oedipus, or at least his complex, Hamlet and his indecision, or perhaps the hypocrisy of Tartuffe?

But if we move beyond the most classic of the classics, the statistics become sobering. Taking German classics, it becomes apparent that they are virtually unknown in the U.S. Opera aficionados and fans of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony know of Schiller, but most theatre-goers do not. In the past 10 years, these 400 American theatres have presented a total of six productions of Schiller—five of Mary Stuart and one Don Carlos. (American regional theatres tend to copy each other; if one produces Mary Stuart, then others may follow suit.) But surely Goethe, at least Faust, would be popular? A survey of these same theatres reveals one poorly received, postmodern adaptation of Faust at an off-off Broadway theatre. That’s it. There was one production of Kleist’s Penthesilea at a minor theatre and, surprisingly, only one production of Büchner’s Woyzeck, also at a small theatre. Zero productions of Lessing. Quickly looking elsewhere around the European canon we find three Racines (and that includes the avant-garde Wooster Group’s magnificent, but extremely idiosyncratic adaptation of Phèdre), two productions of Corneille (both being Tony Kushner’s adaptation of The Illusion), seven Calderons, and nothing of Lope de Vega. (It is worth noting that there is a small off-off Broadway theatre in New York City—Repertorio Espanol—that produces Spanish classics and new Spanish-language plays for a limited audience.) One might reasonably assume that perhaps it has something to do with language. But looking beyond Shakespeare among the Elizabethan and Jacobean repertoire reveals four productions of Marlowe, one each for Webster and Jonson, nothing for Kyd, Ford or the rest of that miraculous age. (For this survey, I am looking at pre-modern classics. Ibsen, Strindberg, and Chekhov, for instance, receive a significant number of productions by American theatre companies.)

It is tempting to cast aspersions on American culture, education, and theatrical taste—an easy target—but I think something else is at work here.

In the history of Western drama, “classical theatre,” technically speaking, refers specifically to ancient Greek and Roman theatre. But more broadly, in much of Europe and Asia it refers either to the foundational drama of the respective societies (noh in Japan, Sanskrit in India, for example) or the work considered to be the literary pinnacle of the culture (Marlowe, Shakespeare, Jonson in England, Corneille, Racine, and Molière in France, Lope de Vega and Calderon in Spain, and, of course, Goethe and Schiller in Germany). Much of this drama originated at those moments at which the particular societies themselves were emerging from chaos or coalescing into a nation. Classical Greek drama matured just as 5th-century Athens was becoming a world power; the drama of late 16th-century England and mid-17th-century France could occur only as each society emerged from the Middle Ages and into a strong, centralized, and prosperous nation. In other words, the theatre is closely identified with the creation of the state or the establishment of a secure society, often in conjunction with the development of a flourishing merchant or professional class. The theatre requires a critical mass of spectators with the time and money to indulge in theatre; and in order for the theatre to attract them it must not merely entertain (that is the job of fairground and market-square performance) but engage the audience by functioning as a medium for discourse with power and official ideology. In a few cases, the theatre may have challenged the status quo, acting as a mouthpiece for the minority or the opposition to authority—think of Beaumarchais’ Marriage of Figaro or the plays of Chekhov and Gorky. In such instances, the theatre was still crucial to the politico-philosophical discourse, playing an active role in the establishment of a new society. In most cases, however, the theatre functioned as a site for rehearsing contemporary politics and social struggles while reinforcing the status quo and advocating the reigning ideologies. Think of Shakespeare in this context.

One might almost think of this as a version of Jacques Lacan’s parle-etre. Only in this case it is perhaps a theater-etre: our knowledge of ourselves and our understanding of the world flow from the way in which it is presented to us onstage.

The playwrights, and the plays that were created in such circumstances, have thus become cultural monuments—they stand equal to the great political and military figures of a country’s history and therefore function as indicators of the worth of the nation. England is a great country, an Englishman might argue, because it could produce Shakespeare. And because Shakespeare has not merely survived for four centuries, but is read and enacted around the world, he is equal to, if not greater, than all the kings and queens he wrote about and served under. Culture surpasses military or even economic might. The French might make a claim for the equal greatness of Racine or Molière while Germans advocate similarly for Goethe, Schiller, and Lessing. To produce the plays is to reinforce the superiority of the culture that produced it. It is also to place one’s self—that is to say, present-day society—in an historical line reaching back to a golden age and glorious past. At the same time, shifting political realities, the inevitable transformation of culture and aesthetics, and the fundamental human impulse to question the structures of the past lead to an interrogation of these classic works. Thus, when a German theatre company, for instance, produces Mary Stuart or Faust, it is, on the one hand, celebrating history, culture, and language, while simultaneously critiquing the very ideas embodied in these plays and thus any current manifestations of those ideologies. National identity and cultural narratives are foregrounded. There is a sense of participating in an ongoing discourse that contributes not merely to the life of the theatre but to the evolution of a specific national or ethnic culture.

In the U.S., however, most such drama is seen as a deictic reference to some vaguely understood past. But our past includes neither the aristocracies, military heroes, nor mythological gods depicted in the canon of classics. In fact, the manufactured mythology and identity that is foregrounded as “American” tends to function in opposition to such entities. If there is a classical drama in the United States, it is nineteenth-century melodrama. Though strongly influenced by continental models—notably the works of Pixèrécourt, Kotzebue, and in particular, Dion Boucicault—it quickly developed a robust American quality. The emphasis on extroverted emotions, and particularly the focus on simplistic notions of right and wrong that typify melodrama, fed into the evolving American narrative of the early 19th century of a simple, agrarian, innocent people whose purity of heart allowed them to overcome the evils of urban and aristocratic Europe. The melodramatic form, of course, ultimately became the foundation of the quintessential American art forms: movies and, later, television. While classical theatre may contain elements of melodrama (Euripides and Schiller are superb examples), the themes and structures of much classical theatre is usually at odds with melodramatic structures and narratives. The thematic and narrative simplicity of traditional melodrama, and its rootedness in local ambience and time-bound character types, has meant that most such plays have not fared well over time.

While the centrality of melodrama within American theatre history, and the close connection between the thematic structure of melodrama and the emergence of an American narrative, qualify the form as American classicism, producing them today is usually problematic. On those rare occasions when classical melodrama is produced, it is most often done with condescension, irony, insincerity, or camp sensibility; it is considered fun, quaint, and anachronistic and the attitude is often one of bemused indulgence—much as we respond to the theatrical endeavors of children. The reception of melodrama is further complicated by its designation as a popular art form, thus making the cultural elite disdainful of melodrama in whatever guise it takes. (Although postmodernism, with its attempt to elide the distinctions between high and low, has allowed a qualified resurrection of popular forms, it rarely does so without a certain intellectual arrogance.) Thus, for melodrama to assume the mantle of classical drama would suggest that America’s is founded upon the lowest manifestations of culture—crude and simplistic entertainment rather than serious art that investigates the past. But with no serious drama created in the U.S. until after World War I, the impulse, the need, for classical drama was satisfied through borrowing from other—primarily European—cultures. But, borrowed classics have at best an ambiguous relationship with their audience. What may have been mimetic in the original, can only be understood as ritualistic repetition in its borrowed form.

Thus, in the United States, “classical” becomes an empty genre—a reference to a group of plays of a certain age, provenance, and cultural stature. To produce these plays, to act in them, or to view them as a member of an audience is not to partake of a connection to a shared past; rather it bestows upon the participants a certain cultural cachet. It implies an intellectual engagement with history and a connection to world culture; it confers an aura of respectability upon the participants and links them to a rarified fraternity of cultural elites. Furthermore, if the production of classic drama in certain European and Asian cultures is a form of mimesis—a recreation of the past—then in the United States it can be understood only as a form of ritualized repetition, reinforcing the cultural significance of theatre with little, if any, socio-historical impact. The U.S., emerging as it did from British Colonial rule, was most immediately and predominantly influenced by British culture. Throughout the 19th century, and arguably through much of the 20th century, the educated, the elite, and the economically and politically powerful were descended from, or willingly influenced by, British sensibilities. In the language-based arts of literature and theatre, British culture set the standards.

However, significant portions of the Colonial population were drawn from the disenfranchised—those seeking escape from the old order or those forcibly ejected from it. If one adds to this the massive waves of immigration, beginning with the Irish and Germans in the early 19th century, and of course the forced immigration of Africans, the result is a majority of the citizenry with alternate models of culture, or at least an opposition to anything associated with the dominant, primarily British, archetypes of high culture. It is not surprising, then, that the mid-19th century witnessed a radical split between high and low art as well as a rift between imported European models and homegrown American culture. Europe experienced its revolutions of 1848, but the United States also had a second small but significant “revolution” at about the same time. In May 1849, the infamous Astor Place Riot occurred in which some 20,000 demonstrators protested the appearance of English actor William Charles Macready while championing the first great American star, Edwin Forrest. Thirty-one people were killed and hundreds injured. There were many factors contributing to this fatal riot, but fundamentally it was a rebellion against the tyranny of European, primarily English, culture and an attempt to establish an American vernacular, which is to say popular, culture in its place. From this point on, the chasm between high and low art expanded at an increasing rate.

Memory

Theatre is both an act and a re-enactment. It is done in the present moment and in the presence of a live audience, so it is immediate; the connection to it is visceral. But it also re-enacts something of the past. On a literal level, it is a re-enactment of rehearsals which themselves are the embodiments of an author’s text. The text of most classical theatre—and clearly I am talking about a traditional form of theatre—is itself a re-enactment of an historical or mythological moment. It is a form of memory. And like all memories, it can easily be distorted and mis-remembered. Technically speaking, only someone who has experienced something can remember it. But there is a human desire or need to partake of the past and therefore to assume and incorporate memories second-hand. Within our personal lives, there are family stories that are passed on from generation to generation, so that those persons long removed from the actual event “remember” it. There are public events which we “remember” even if we were not there. The same is true for societies and nations. We remember national triumphs or defeats; and, tragically, one community may remember how they were ill treated by their neighbors and carry this memory with them for generations, even for centuries. And just as photographs aid in the transmission of personal and familial memories, so does theatre function in the preservation of national and ethnic memories.

This raises the question, then: if a classical European or Asian play is done in an American theatre, what is being remembered? What is being transmitted? I would suggest that in large part, classical theatre is produced in the U.S. as part of a project to link American theatre—American culture—to the roots of theater and to older traditions, thereby conferring respectability on the enterprise and placing the current American production in a line that can be traced back to Aeschylus. While some immigrant communities may still retain the cultural memories of the places from whence they came, most audiences, confronting classical drama are experiencing a more fundamental but also generic sense of history itself—not the specific historical incident of the play or its meaning for a particular society, but simply the idea of history or, what I might call, “pastness.” This photo from a 1998 production of Mary Stuart at the American Conservatory Theatre in San Francisco shows the characters of Elizabeth I and Robert Dudley.

Figure 1

The costumes by Deborah Dryden are painstakingly researched and lavishly created and the reviews suggest that the critics, and presumably the spectators, were appropriately impressed. But as much as these costumes might represent a particular historical moment, they are, for most spectators, an ambiguous semiotic indicator of the past and, perhaps, of the very notion of theatre itself. Audiences, particularly patrons of cultural institutions, expect that certain forms of theatre, opera, and film will have costumes that look like this; such productions, in fact, are designated by the term “costume drama.” It becomes a tautology: as a classic it must have these kinds of costumes, and because the production has such costumes it must be classic theatre. The costumes in this photo are ultimately a semiotic code representing historical accuracy for an audience largely ignorant of the details of period dress. How many spectators would know, or care, whether the size of the collar, the texture and pattern of the fabric, the details of the jewelry, or the hairstyles are accurate representations of the dress of the 1580s? For the audience of this production, these indicators may have equally referenced Katharine Hepburn in the 1936 film, or Vanessa Redgrave in the 1971 film version of the story, as much as it does any historical figures. Our sense of history has been shaped by Hollywood. Similarly, it references a range of historical epics produced by British television and broadcast in the U.S. as an antidote to the lowbrow fare of most commercial TV. It is not accidental that the umbrella title for the series that showcases classy British television in the U.S. is “Masterpiece Theatre” with its implications of high art and cultural significance. The costumes themselves project an aura of culture at its highest level.

This photo from a 2001 production of the same play, directed by JoAnne Akalaitis at the Court Theatre in Chicago, suggests a more modern approach—a costume, designed by Kaye Voyce, with an appropriate period silhouette and historical touches, yet one that in its self-referentiality and self-consciousness is fundamentally modern.

Figure 2

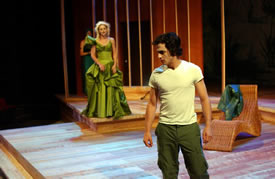

It acknowledges historicity while proclaiming its contemporary pedigree. It says, in essence, “I recognize the precedents of this play—both historical and literary—but I am equally aware of my position within the present day.” And of course there is the postmodern pastiche approach as seen in this 2002 production of Phèdre, again by Akalaitis and Voyce at the Court Theatre.

Figure 3

This production would like to suggest that there is no difference between past and present. The pastiche of contemporary costumes—some prosaic, some more formal with a slight reference to the past—proclaim the play’s modernity and thus relevance. The past is present and the present is past. But this image in particular highlights the problems faced by American productions of so-called classics. We have no historical memory of monarchs; despite the volatile and deadly results of politics, we tend to have a low opinion of our leaders and treat them as the punchline for jokes; the supposedly egalitarian spirit of American democracy eschews class and the trappings that go with it. Thus, the hierarchies and power structures implicit in the play are poorly understood or imperfectly received by audiences. So, Phèdre’s dress, though suggesting a certain elegance, is simultaneously parodic. The costume, hair, and bodily pose semiotically render lust, degradation, madness, and the debasement of nobility, but at the same time it mocks these emotions and social indicators. Hippolytus can, apparently, be understood only as a rebellious teenager in a tee shirt. It is as if we can understand these characters only as current-day party-goers, denizens of the chic clubs or hip neighborhoods to be found in New York, London, or Paris. Interestingly, by placing Hippolytus in this costume the director and designer seem to be referencing one of the classic iconic images of American theatre: Marlon Brando as Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. But if this was, in fact, their intention, to what point? It typifies much misguided American postmodernism in its seemingly random juxtaposition of images whose relevance is minimal at best. It suggests either that all images are equally significant, or else a belief that the tension or energy created by the fusion of iconic images will render something new and noteworthy.

There is another factor that must be taken into account in examining the American approach to classics. The American drama that has become the foundation of our theatre—our classics—is psychologically based: the plays of Clifford Odets, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, William Inge, even Edward Albee, up through Sam Shepard and David Mamet all emanate from a psychological exploration of characters who are, at least on the surface, prosaic individuals. This paradigm, of course, is reinforced through television and film. Thus, approaches to the classics often grasp at a kind of psychological realism, trying to find the psychological and emotional reality of Clytemnestra, Lear, or Mary Stuart—reducing them to characters out of action movies or soap operas. While most of the characters of classical drama have a psychological dimension—that is part of their appeal, after all—there is often a formalism or operatic quality to the plays that mitigates against a realistic approach that can lead to bathos. By dressing characters in pedestrian clothing as in so many postmodern renderings, it has the effect of reducing them from theatrical creations to avatars of ourselves.

The stage itself, however, has abandoned any attempt at pictorial realism. That approach is too closely associated with late 19th-century realism and melodrama and has been subsumed by film which can render reality much more literally. Thus, the stage becomes an emblematic domain at once referencing the past and itself. By acknowledging its existence as a stage it proclaims its theatricality, yet by use of emblematic images it references history as in Ming Cho Lee’s stark setting for Don Carlos at the Shakespeare Theatre of Washington, D.C.

Figure 4

My discussion might seem to suggest that Americans should not do classic theatre. Insofar as it is done as costume drama and psychological investigation, that would, in fact, be my recommendation. Such theatre is the embodiment of what Peter Brook categorized quite accurately as “deadly theatre.” It is nothing but an empty gesture toward the past and toward high culture. Similarly, much postmodern production is equally empty—maintaining the original text but problematizing it through contemporary costume and pastiche scenography. I am not suggesting that classical theatre has nothing to say to us, however, but what it has to say is based on larger thematics and on its connection to theatricality at large. So there is one potentially fruitful approach, one taken most successfully by the Wooster Group in its approaches to American and European classics such as Chekhov’s Three Sisters and Racine’s Phèdre. What the group, under the direction of Elizabeth LeCompte, has done is to re-frame the works. The original frames, of 17th or 19th-century French or Russian theatre, have no meaning in late twentieth or early 21st-century American theatre. To say they have no meaning is really to say that the vocabulary of the older theatres is largely incomprehensible. The plays cannot be read in this now obsolete theatrical language. At best, we understand them semiotically as classical plays. By finding new physical, narrative, and even technical environments in which to explore the original texts, characters, and themes, the underlying impulses and meanings of the playwrights can re-emerge. It is a difficult process and theatres that have attempted to copy the style and approach of the Wooster Group have often wound up with results as deadly as historical costume dramas. But in a country with no history, in a country that now has multiple historical narratives built upon the most diverse population in the history of the world, straightforward renderings of the classic drama of other cultures and societies is going to be problematic at best.

Finally, I must return to Shakespeare. Having just argued that the U.S. cannot do classical theatre, I also cited the statistic of 540 productions of Shakespeare’s plays. I will offer two explanations. One has to do with education. Shakespeare is the one writer of classical drama who is taught with any regularity. Students are exposed to some of his work repeatedly throughout their schooling, his plays are sometimes produced in high schools, and students are often dragged off to see professional productions (of widely varying quality). Thus, Shakespeare is seen not so much as a dust-laden relic of the past as a contemporary, albeit one with difficult language. Then there is the high-low dichotomy. Even in his own time, part of Shakespeare’s success stemmed from his ability to appeal simultaneously to multiple audiences and levels of reception. During the 19th century, this appeal continued with touring productions that played in saloons and mining camps in the West as well as in legitimate theatres. So even today, Shakespeare is sold as both popular entertainment and high art. On some level, many American audiences think of Shakespeare as an American playwright. There are dozens of Shakespeare festivals across the country, most operating as summer tourist theatres. And many produce as much non-Shakespearean drama as Shakespearean—so that Shakespeare has become almost a synonym for summer theatre. The question is, if Goethe were taught in American schools, and if there were dozens of Goethe festivals across the country, would he—or any of the others—become equally Americanized?

--------------------------

* Statistics come from “Theatre Profiles” published by Theatre Communications Group. http://www.tcg.org/frames/member_profiles/fs_thprofiles.htm

Figure 1. Caroline Lagerfelt and Marco Barricelli as Elizabeth and Robert Dudley. Costumes by Deborah Dryden. Photo: Ken Friedman.

Figure 2. Mary Stuart at Court Theatre, Chicago. Costumes by Kaye Voyce. Photo: Michael Brosilow

Figure 3. Phèdre at Court Theatre, Chicago. Jenny Bacon as Phèdre, James Elly as Hippolytus. Costumes by Kaye Voyce. Photo: Michael Brosilow.

Figure 4. Don Carlos at Center Stage, Baltimore. Set by Ming Cho Lee. Photo: Carol Rosegg