HOTREVIEW.ORG - Hunter On-line Theater ReviewDemands for Empathy

By Martin Harries

The Threepenny Opera

By Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill

Brooklyn Academy of Music

(closed)

1.

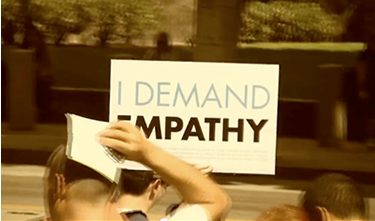

A still:

What first person demands this, and of whom? Is this a symptom of the incoherence those hostile to the occupy movement seek in its manifestations, or is it the core of the call for economic justice? This positive demand for an affective response does not accept the blindness to consequences that describes the signature of the invisible hand. Its dislocation of a struggle over economic injustice to the sphere of affect might also, however, defuse the force of the critique: if you feel my pain, I will go home and occupy the private space where you think I belong. Further, the demand for empathy might undo the material basis of the movement's protests against massive inequality.And yet one might also give the sign credit for a more mischievous canniness, about finance, politics, and empathy alike. Far from the na´ve call for palliative fellow-feeling, for the corporate citizen condescending to stoop to imagine my place as his, her, or its own, the sign's demand may register precisely the impossibility of such recognition: such empathy does not belong to the corporate world. For the mere act of asking for it reveals the inhuman autism of the corporate "person" and mocks the idea that any such empathy might ever take meaningful or material form. The demand for this empathy includes the demand for economic justice that would make empathy meaningful. Until then, there can be no empathy: it doesn't belong in this theater.

2.Brecht famously complained that the established theatrical apparatus of his day could neutralize any content. In notes he wrote in the connection with The Threepenny Opera, he famously complained:

The theater apparatus's priority is a priority of means of production. This apparatus resists all conversion to other purposes, by taking any play which it encounters and immediately changing it so that it no longer represents a foreign body within the apparatus -- except at those points where it neutralizes itself. The necessity to stage the new drama correctly -- which matters more for the theater's sake than for the drama's -- is modified by the fact that the theater can stage anything: it theaters it all down.

Brecht was worried that the opera he, Kurt Weill, Elizabeth Hauptmann, and others had produced might have neutralized itself on the way to its success, might have become something other than the subversive "foreign body" inside the apparatus that they had hoped to lodge there. The play's political purpose had become the purpose of the apparatus, "theatered down" to entertainment. Robert Wilson's encounter with The Threepenny Opera raises similar questions: Will the Wilson machine resist "conversion to other purposes" or will it change in response to the "foreign body" of Threepenny? The spotlights, the elegantly lit cyclorama with the complicated sequences of perfectly calibrated sheets of color, the entr'actes played before the curtain, the almost tortured choreography of angular bodies, the late expressionist glitter and doom making up the actor's faces: could anything give? In short: no. The Wilson apparatus proved invulnerable to any potential subversion that Brecht and Weill's piece might yet hold.

What, then, of the much-repeated notion that Wilson was in some way intended to direct The Threepenny Opera? "My own opinion is that Robert Wilson was destined to confront the superior ensemble work of the Berliner Ensemble and to wrestle with the material of Threepenny Opera," said Joe Melillo, Executive Director of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. This is puffery, of course, but maybe more than puffery, and it points to another question. Maybe a better question. Not: in what way does The Threepenny Opera change the apparatus that is the Wilson stage machine? Rather: in what way might the essence of the work have been lurking there all along?

Wilson has for some time now been searching for his Brecht and Weill: collaborations with Tom Waits and William S. Burroughs, with Lou Reed and Edgar Allan Poe, and other such confabulations, have visited Brooklyn and toured the world, but none has yet caught fire in Wilson's era as Threepenny did in Brecht and Weill's. (It's true that the recent collaboration between Lou Reed and Metallica began with songs Reed wrote for Lulu, a Wilson production based on Wedekind, so maybe Wilson has found his Bobby Darin. Probably not.) He's clearly looking for the edgy-popular, and longing for a commercial hit. Imagine, say, Alice -- the 1992 collaboration between Waits, Wilson, Paul Schmidt, and Lewis Carroll -- running for two years on Broadway and you have something like the shock of the initial success of Threepenny.

All the productions just mentioned might be seen as would-be successors to Threepenny, which invite us to ask what Brecht (or the emulation, or envy, of Brecht) makes newly visible in Wilson. Those whited sepulchers passing for characters, that frigid precision that makes stage pictures as alluring as they are isolating, those stabs at humor that seem like slapstick for an audience that has forgotten how to laugh: the Wilson apparatus has always appeared to resist incursions from a political or social world outside it. The sheer ease with which that apparatus subsumed Threepenny into itself, then, might lead one to think, to paraphrase Brecht, that Wilson wilsons the politics all down: the foreign body of political content becomes part of a formal experiment that neutralizes it.

Such an indictment raises larger questions about what political force can possibly survive the festival circuit and the ever-receding, ever-returning next waves of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. These are beyond the scope of this essay. But let me nibble at the corner of them via a face.

3.

Right now, in late 2011, this face has a particular pop-culture referent. With its exaggerated eyebrows, the goth outlining of the eyes themselves, the deathly whiteness of the skin, it recalls nothing more vividly than the petrified mask of V in V for Vendetta, the comic mask of the revolt against the security state. The revivified Guy Fawkes of graphic novel and film is omnipresent nowadays: in the global reoccupations of public space, his mask -- "the jokey icon of festive citizenship," as Jonathan Jones calls it in The Guardian -- has appeared everywhere in assemblies. This evocation of V recalls especially the climactic scene of the film, where thousands of anonymous Londoners don identical masks in preparation for V's explosive demolition of the Houses of Parliament. Yet the iconological roots of the mask go much deeper, as Jones argues, deep into the carnival culture of Europe. And these roots inform Wilson's pale creatures. Why these white masks now?Consider the women in Wilson's Threepenny. The superbly agile performers of the Berliner Ensemble made Wilson's exaggerated versions of gendered movement all the more startling. The abjection of the women, coerced into absurd postures, emphasized the isolation into petrified gender roles that is one feature of Brecht's text. In the opening scene, Mrs. Peachum (Traute Hoess) was especially constrained, moving as if in some Teutonic rendition of a geisha's movements, with touches of a shorebird's shuffling and pecking. Then her transition into song was striking: singing of the moon over Soho at the end of that scene, Hoess was transformed into someone very different, powerful and enlivened.

"When an actor sings," Brecht wrote in his commentary on Threepenny, "he undergoes a change of function." Here that change included a female performer refusing the femininity Hoess had evoked and exaggerated a moment before. "His aim," Brecht writes further of the actor who sings, "is not so much to bring out the emotional content of his song (has one the right to offer to others a dish that one has already eaten oneself?) but to show gestures that are so to speak the habits and usage of the body." With Hoess and all the show's performers, their change of function during singing brought out habits and usages of a potential body, of a self sometimes quite radically different from the one seen constrained at other times. The songs did contain the charge of "emotional content," as expected in musicals, but this content was also the site of a political charge: masks fell, or different masks became visible.

It is strange that Polly Peachum sings one of the most beloved of Threepenny's songs, "Pirate Jenny"--strange because soon enough we also encounter a character named Jenny, who might just as well sing the song. This repetition, as though there weren't enough names to go around, is part of the point: in singing from the standpoint of the harassed barmaid who knows that a ship with eight sails and fifty cannon is soon to come in and rescue her, Polly sings for Jenny, too. The actress Stefanie Stappenbeck, whose "Pirate Jennie" was one of the highlights of the evening, owned this song, so to speak, by giving it away--by understanding the deep engagements implied by Brecht's understanding of the songs. The political content didn't have to do with the actor, in the theatrical or the political sense, but rather with a potentiality to change one's place, which belongs to everyone and anyone. For all its frozen style and the elaborate control over the choreography of every movement, this production brought home the destabilizing force of this ability to change one's skin. It may be that the Wilson apparatus, with its Grand Guignol parade of pale masks of the neoliberal order, has always contained a ghastly suggestion of something like this power to transform.

The carnival promise--you become the mask you wear--is also always a kind of threat: you may be not Polly, but the pirate incognito.

Furthermore: a lack of certainty about who the other might be always complicates empathy. What connects the occupation under the sign of V and a rarefied production of Brecht is not only a carnivalesque challenge to certainties about self and other, but also the latent threat that comes with that challenge.

-----------------------------

Threepenny Opera photos copyright Stephanie Berger.