Brilliant Gestures

By Caridad Svich

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber

of Fleet Street

By Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler

Eugene O'Neill Theatre

230 W. 49th St.

Box office: (212) 239-6200

The new Broadway production of Stephen

Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler's Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber

of Fleet Street, directed and designed by John Doyle, bristles

with imaginative energy and supple strength. Stripped down to

a ten-member singer-actor-musician ensemble led by Michael Cerveris

and Patti Lupone, the cast makes even a longtime fan of the show

feel she is hearing the score for the first time. Sondheim's score

(with lyrics by Sarah Waters) is indeed the life-blood of this

bitterly macabre and strangely tender 1979 musical. What mainly

engages the eye and ear this time, however, are Doyle's choices,

the intricate, imaginative dance he asks of his audience.

This is a ritualized, madhouse re-telling

of the Sweeney story on a stage flanked by a cross-like formation

of coffins on a wall of used and unused props and relics. Doyle

dresses the musical down to the bone, demanding that the audience

fill in the "scene," as it were, and at the same time look closely

at it. This act of visual doubling--the real stage set against

imagined scenes forged from the re-enacted story--is further complicated

by having actors playing their own instruments. The young, doomed

lovers Johanna (Lauren Molina) and Anthony (Benjamin Magnuson)

play their love duets accompanied by their cellos. Judge Turpin

(Mark Jacoby) shares trumpet phrasing with The Beadle (Alexander

Gemignani) as they scheme. And young, crazed, initially straight-jacketed

Tobias (Manoel Felciano) plays the violin as if the strings were

extensions of his feverish, tormented mind. The multiple tasks

of the actor-singer-musicians invite complex responses from the

audience and the cast. Characters who die in one scene pick up

their instruments in the next, suggesting that the telling of

this story is never-ending, and that the murdered are haunted

by their killers even in "death."

The multi-layeredness awakens the audience

to listen sharply, imagine intently, and witness the acting and

musicianship with a measure of attention that is unusual for standard

Broadway fare. While not robbing the piece of its penny dreadful

origins, and the requisite thrills of a story that depicts revenge

with relentless obsession, Doyle's exacting, highly stylized vision

demands much of the audience. There's no seduction by the beauty

of the score or the romance of the performances. The story of

the murderous barber lives, here, in the audience as much as on

the stage.

That is not to say that there is nothing

without the audience, for the recently released cast recording

of this production affirms the magnetic grace and delicate musicality

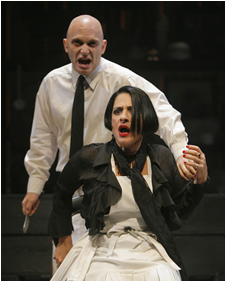

of the ensemble. Cerveris's Sweeney sits in his lower vocal register,

intoning his loss and vengeance as if from a great un-located

depth. Clad in black leather and heavy boots, shadowed in sculptural

light (evocatively designed by Richard G. Jones), he exudes blank-eyed,

chilly menace: a figure lost to himself, forever exacting loss

from everyone around him.  LuPone's

Mrs. Lovett is a jazzy contralto, casually, cold-heartedly scheming

for adventure while egging her alienated but compliant servant-lover

to kill. Decked out in a tight-fitting black mini-skirt and corseted

top, she is a feral mistress cast in the Wedekind mold. Cerveris

and Lupone's deadly dance of Eros and madness, equally brutish

and intimate, continually captivates even when they are not ostensibly

in a "scene." Felciano's Tobias, from whose point of view Doyle

chooses to tell the tale, is a guileless, childish creature with

the voice of an ardent angel and the stare of a wayward son. His

reading of the ballad "Not While I'm Around," sung to Lupone's

unashamed mother/lover embrace, is so full-hearted that it almost

threatens to break the spell of this relentlessly revisionist,

cold-lit Sweeney and thrust it into the brooding, soulful mood

of a later Sondheim piece like Passion.

LuPone's

Mrs. Lovett is a jazzy contralto, casually, cold-heartedly scheming

for adventure while egging her alienated but compliant servant-lover

to kill. Decked out in a tight-fitting black mini-skirt and corseted

top, she is a feral mistress cast in the Wedekind mold. Cerveris

and Lupone's deadly dance of Eros and madness, equally brutish

and intimate, continually captivates even when they are not ostensibly

in a "scene." Felciano's Tobias, from whose point of view Doyle

chooses to tell the tale, is a guileless, childish creature with

the voice of an ardent angel and the stare of a wayward son. His

reading of the ballad "Not While I'm Around," sung to Lupone's

unashamed mother/lover embrace, is so full-hearted that it almost

threatens to break the spell of this relentlessly revisionist,

cold-lit Sweeney and thrust it into the brooding, soulful mood

of a later Sondheim piece like Passion.

The rush of positive, powerful feeling

from Tobias, however, is ultimately in keeping with the go-for-broke

take on the score from the rest of the performers, whether they

are in romantic counterpoint (in Sweeney and the Judge's duet

"Pretty Women"), in rock n'rollish mania (in Sweeney's "Epiphany"),

or in flirtatiously wistful dreaming (in Mrs. Lovett's "By the

Sea"). Indeed, the power of Felciano's fervor in "Not While I'm

Around" is an effective reminder of Sondheim's ability to place

the beating heart of his scores often in secondary, less showy

roles. Very likely, Doyle's decision to conceptualize this Sweeney

from Tobias's point of view was cued from the score itself--as

director-choreographer Matthew Bourne took his carnal, surreal

approach to Swan Lake from the pulse and swoon of Tchaikovsky's

score. Tobias has pledged his loyalty to Mrs. Lovett and vowed

to protect her from all harm (not knowing that she is complicit

in Sweeney's crimes). He surrenders to her in song, and his vow

becomes the axis from which the rest of the show pivots. As Sweeney's

murderer, innocent, troubled Tobias is the one most haunted by

this lurid story, for it is Sweeney's eyes in death that will

forever follow him as he lives on in the asylum that offers no

true mental sanctuary.

The design is Expressionist throughout,

with an especially compelling and macabre use of a child's white

coffin cradled by Sweeney in the second act. Doyle may have been

influenced by Peter Brook's asylum-set in Marat/Sade

but, again, he seems primarily emboldened by the source material

itself. Radically reducing the mise-en-scene and the

orchestrations from the operatic and brazenly flamboyant stagings

of Sweeneys past (including Harold Prince's remarkable

original production), Doyle seeks to relocate the core of this

burning tale of mad passion and rage, and give it classical meaning

and proportion. Starkly presented, with its violence staged through

symbolic gestures enhanced by flashes of red light and buckets

of blood, it references the lurid thrills of Grand Guignol. Yet

in our age of reproduction and replication, when images of violence

and horror (fictive and real) are all too common, the excitement

of this Sweeney Todd is not in the depiction of violence

but in the knowledge that these figures, however startlingly fashioned

by pulp conventions, are part of our moral order. Their gestures,

full and empty at the same time, re-told yet fresh, are inescapably

human. And the more we listen to Sondheim's score, with its passages

of brilliance, vaudevillian flourishes and mournful cadences,

the more its human-ness, its outrage and wonder at what individuals

are capable of, transforms the cheap thrills into a penetrating

examination of the dangerous aspects of the human heart.