Bodies That Matter

By Gitta Honegger

Ulrike Maria Stuart

By Elfriede Jelinek

Thalia Theater

Hamburg, Germany

The Nobel-laureate physicist Max Planck

once remarked that for a new idea to succeed the old generation

of scientists and their students need to die. For the following

generation the new will then be an obvious fact. This somewhat

gloomy prospect seems to apply to theatrical innovations as well.

Directors and designers trained in the former West Germany have

not yet gotten over the influence of Robert Wilson in their pristinely

lit, meticulously contoured, slow-motion Gesamtkunstwerke,

expanding already lengthy classics by hours of mega-minimalist

mise-en-scènes.

By contrast, a younger generation of directors

was influenced by the East Berliner Frank Castorf (born 1951),

the provocative artistic director of the Volksbühne am Rosa Luxemburg

Platz, whose over-the-top stagings of Dostoyevsky, Frank Norris

and Tennessee Williams, among others, defined the post-dialectical

merger of Communist and global Capitalist greed, angst and desire

in the reunited Germany.

Not surprisingly, Wilson's signature slow-motion

aesthetic (which drained his staging of Georg Büchner's Woyzeck

at the Berliner Ensemble of all socio-political pathos) was recently

parodied at the Volksbühne by Christoph Schlingensief, the German

playwright, director and filmmaker. Schlingensief's play Rosebud,

which he wrote and directed in 2001 in the wake of 9/11, was a

savage send-up of terrorist plots by and against fame-starved

journalists, dysfunctional media executives, and their abused

and abusive children in a world that can perceive itself only

in terms of staged performances. Among other outrageous appropriations

from stage and screen, construction workers (a ubiquitous sight

in post-Wall Berlin) in primary-colored hard hats and costumes

criss-crossed the stage sideways, Wilson-style, their glacial

speed also suggesting the tempo of workers protected by government-controlled

wages and benefits. Born in 1960, Schlingensief is arguably the

naughtiest and most cheerfully tasteless among the stars of the

so-called "post-dramatic theater." His in-your-face infantile

theatrics belie the seriousness of his attacks on cultural pretense

and contemporary politics.

One of Elfriede Jelinek's favorite directors,

Schlingensief staged the scandalous 2003 premiere of her play

Bambiland at the Vienna Burgtheater. This characteristically

dense text was Jelinek's response to the war in Iraq, particularly

to Abu Ghraib and its connection to her vision of Austria as an

ongoing pornographic spectacle involving its historical undead.

Schlingensief's staging included his response to the material,

which he broke up with improvised scenes and interviews with different

guests every night, alternating with porn sequences on a giant

screen. Turning the venerable Burgtheater into a gilded porno

house harked back to the spirit of Jelinek's earlier play Burgtheater

(never done at the Burgtheater) in which she exposed Austria's

most revered actress, Paula Wessely, as an ardent supporter of

Hitler. Wessely had starred in the Nazi propaganda film Die

Heimkehr (The Homecoming).

It was Castorf's aggressive 1994 staging

of Jelinek's Raststätte (Rest Area) at the Hamburg

Schauspielhaus that became a defining model for dealing with this

Nobel laureate's resistant texts. That was the first time a director

had used the production circumstance as an open confrontation

with the author, who was introduced as a monstrous sex doll, with

braids, signature hair-roll, and all. Jelinek-wigs began to appear

like fetishes in subsequent productions of her plays. Whenever

directors got lost in Jelinek's syntax -- or her jungle of quotes

appropriated from literature, pulp fiction, the media, advertising

and politics -- they would stage their frustrations in their productions.

The late Einar Schleef (1944-2001) famously appeared in his production

of Sportstück as the author's stand-in, named Elfi-Elektra,

and screamed in desperation: "Frau Jelinek, I don't understand

you."

Interestingly, male star directors produced

the most acclaimed productions of her plays, enacting a strange

sort of mating ritual that might be called a "mind fuck" in the

language of Jelinek's generation. Over a decade ago, Jelinek abandoned

dialogue in favor of what she called Sprachflächen --

language planes -- a term that has become a cliché in academic

criticism of her work. The term, however, accurately describes

the surface the directors furiously confront. Whenever they find

themselves running up against a wall, they smash their way through

it, with Jelinek's permission, with the force of a wrecker's ball

(a term that would suit her delight in the tackiest sort of punning).

In her stage directions for In den Alpen (In the

Alps) she advises prospective directors: "As everyone knows

by now, I couldn't care less about how you're going to do that."

"Feel free to fuck around with me," she encouraged Nicolas Stemann,

who directed three of her plays, including the Hamburg premiere

of her most recent, Ulrike Maria Stuart.

In

a sense, her directors enact upon her text-as-body what she stages

in her writing. Her scenarios are littered with dismembered body

parts that suggest the cannibalism of commercially produced desire.

Austrian natives gnaw on the severed limbs of skiers, mountain

climbers and refugees who perished in the Alps -- a special temptation

for directors with a knack for Grand Guignol. Stemann, in his

2005 Burgtheater production of Jelinek's Babel, inserted

a text by an actual contemporary cannibal, Issei Sagawa, who meticulously

described luring, killing, preparing, ingesting and storing the

body parts of a young German woman he met in Paris in 1981. The

text was read by a beautiful, soft-voiced Asian actress. (Released

from a Japanese mental institution after 15 months, Issei Sagawa

became a cult figure, who now maintains his own Web site and has

been featured in a French gourmet magazine, among other publications.)

In

a sense, her directors enact upon her text-as-body what she stages

in her writing. Her scenarios are littered with dismembered body

parts that suggest the cannibalism of commercially produced desire.

Austrian natives gnaw on the severed limbs of skiers, mountain

climbers and refugees who perished in the Alps -- a special temptation

for directors with a knack for Grand Guignol. Stemann, in his

2005 Burgtheater production of Jelinek's Babel, inserted

a text by an actual contemporary cannibal, Issei Sagawa, who meticulously

described luring, killing, preparing, ingesting and storing the

body parts of a young German woman he met in Paris in 1981. The

text was read by a beautiful, soft-voiced Asian actress. (Released

from a Japanese mental institution after 15 months, Issei Sagawa

became a cult figure, who now maintains his own Web site and has

been featured in a French gourmet magazine, among other publications.)

The German popular press routinely reacts

to Jelinek with personal attacks of astonishing viciousness. As

if to protect her body in her texts from these media assaults,

she recently declared that, starting with Ulrike Maria Stuart,

her work will no longer be made available in print. Instead, she

would only post the texts on her Web site. An early version of

Ulrike Maria Stuart popped up there for a just a few

days several months before the Hamburg premiere.

Perhaps this policy will be temporary.

In any case, it has turned out to be unexpectedly fortunate. One

of Ulrike Meinhof's twin daughters, Bettina Röhl, a journalist,

threatened Jelinek with a lawsuit for distortion of her mother's

relationship with her children and for violation of the family's

right to privacy. The daughter had attended an open rehearsal

of Stemann's Hamburg production and then offered to help with

rewrites and directing. Her offer was declined. Since the play

had not been published, there were no concrete grounds for legal

action. Nevertheless, some changes were made. Jelinek's publisher,

Rowohlt Verlag, sends out the script to theaters with a proviso

that they are prohibited from distributing it outside the production

cast and crew. The implication is that each production must be

considered the current text, and that only the producing theaters

can be held legally responsible for its contents.

According to the German magazine Der

Spiegel, Röhl was satisfied with the changes Stemann made

-- changes, one assumes, to personal references and quotes. I

attended both a public rehearsal and the opening night performance

and thought that, though the lost lines were relatively unimportant,

the production had lost a bit of its aggressive edge.

The unavailability of the printed text

adds an intriguing dimension to the experience of the theatrical

event: remembering details of the performance parallels the remembering

of the historical event through layers of mediatized narratives.

Unlike the actual past, one can return to the theater to watch

another performance. However, due to the uniqueness of each theatrical

evening, it will not be the same. Ultimately, the work remains

as elusive and subject to multiple perceptions as events that

happened in the past. In any case, Jelinek's new strategy gives

directors even more freedom than they had had. From now on they

are the authorized co-producers of the performance text.

Jelinek's exemplary, self-negating move

fulfills the claims of a "post-dramatic theater" that no longer

privileges the text. This move will require critics to radically

rethink their analytical tools and, so far, the German press,

used to directorial excess and authority, has happily ignored

the challenge. They have continued to apply their standard repertoire

of adjectives and witticisms to both her works and her directors'

stock of "post-dramatic" devices.

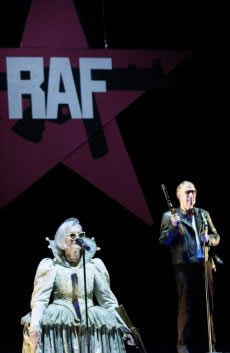

Jelinek's Ulrike Maria Stuart

examines the legacy of West Germany's Left through the dynamics

of women in power. Friedrich Schiller's fictional encounter between

Mary Stuart and Elizabeth I is refracted in the relationship between

Gudrun Ensslin and Ulrike Meinhof, the driving forces of the activist-turned-terrorist

Baader-Meinhof group. With Andreas Baader they were the founding

members of the Revolutionary Army Fraction or RAF. What began

as a protest against their parents' generation's unwillingness

to deal with their Nazi past and a rebellion against the war in

Vietnam and the excesses of capitalism escalated into a series

of deadly terrorist attacks.

The drawn out, controversial trial of key

members of the group in Stuttgart in the late seventies marked

the climax of the most violent phase of West Germany's post-war

history. Ulrike Meinhof hanged herself in her prison cell. A year

later Gudrun Ensslin found the same death in the same cell, while

Andreas Baader and two other members were discovered shot to death

in their cells. (It was never clearly established that their deaths

were suicides.) Earlier, another imprisoned member, Holger Meins,

died from a hunger strike.

As usual, Jelinek is not interested in

dramatizing the stories of individuals. Though Ulrike, Gudrun

and the "Queen" are featured speakers, their language reflects

their construction as composite ready-mades. A dizzying kaleidoscope

of splintered references merges in Jelinek's grammar to suggest

a trail of thought leading from the Elizabethans to German Idealism

to Communism to Nazism to the sixties to global capitalism, outsourcing,

the Middle East, Antigone and contemporary petty-middle-class

consumer culture -- which, it turns out, is at the root of the

group's demise. The quotes include Schiller, Shakespeare, Büchner

and Marx, as well as the writings of Meinhof and other RAF members.

These last become material for a bitterly satiric take on failed

revolutions, the self-delusions of rebels (including perhaps Jelinek's

own), and the commodification of revolution in the post-ideological

age.

The

voices of "Princes in the Tower" representing Meinhof's children

(the primary cause for the "real" daughter's concerns), a "Chorus

of Old Men" and an "Angel from America" trying to hang himself

with his AIDS ribbon (a homage to Tony Kushner) connect different

periods and cultures. Jelinek owns the DVD of Angels in America

and watched it many times with great enthusiasm. It inspired her

to insert several appearances by an "Angel from America" in her

text. His role is the most puzzling. His initial warning that

terrorism invariably leads to a reactionary backlash, his wrathful

and increasingly anxious ruminations over traditions, miscalculations

and self-destructive strategies of the Left suggest an outsider's

perspective. (Jelinek ardently admires Kushner's own struggle

with and for the democratic ideals of the American constitution.)

Given the concrete political and existential struggle Kushner's

Angel represents, Jelinek appears to question both the romanticizing

of past revolutions and the indulgences of so-called "post-dramatic"

performance practices (which have been partly spawned by her texts)

-- although, curiously, there are no allusions to contemporary

terrorism and American politics, as in her previous play Bambiland.

Then again, the Angel occasionally adopts the self-absorbed language

of Andreas Baader. At other times, from his new vantage point

close to the Lord, he seems to have refined his political views

and sharpened his sense of irony regarding God and the world.

Her brand of comedy is based on the disconnection between human

efforts to make sense and categorical denials of that just when

it is about to happen.

The

voices of "Princes in the Tower" representing Meinhof's children

(the primary cause for the "real" daughter's concerns), a "Chorus

of Old Men" and an "Angel from America" trying to hang himself

with his AIDS ribbon (a homage to Tony Kushner) connect different

periods and cultures. Jelinek owns the DVD of Angels in America

and watched it many times with great enthusiasm. It inspired her

to insert several appearances by an "Angel from America" in her

text. His role is the most puzzling. His initial warning that

terrorism invariably leads to a reactionary backlash, his wrathful

and increasingly anxious ruminations over traditions, miscalculations

and self-destructive strategies of the Left suggest an outsider's

perspective. (Jelinek ardently admires Kushner's own struggle

with and for the democratic ideals of the American constitution.)

Given the concrete political and existential struggle Kushner's

Angel represents, Jelinek appears to question both the romanticizing

of past revolutions and the indulgences of so-called "post-dramatic"

performance practices (which have been partly spawned by her texts)

-- although, curiously, there are no allusions to contemporary

terrorism and American politics, as in her previous play Bambiland.

Then again, the Angel occasionally adopts the self-absorbed language

of Andreas Baader. At other times, from his new vantage point

close to the Lord, he seems to have refined his political views

and sharpened his sense of irony regarding God and the world.

Her brand of comedy is based on the disconnection between human

efforts to make sense and categorical denials of that just when

it is about to happen.

Jelinek's response to the Nobel Prize is

a case in point. Her agoraphobia and other acute anxieties made

it impossible for her to attend the award ceremony. Her radical

withdrawal from the public after receiving the Prize is reflected

in Meinhof's increasing isolation from her group. Meinhof had

been a journalist and her political pamphlets, reflective texts

and partly critical notes on the history of the RAF were rejected

by Ensslin and her lover, Andreas Baader, who had also been Meinhof's

lover. The contradiction between the women's radically anti-bourgeois

revolutionary project and their old-fashioned rivalry for a man

recalls the role of Leicester in Schiller's fictional encounter

between Mary Stuart and Elizabeth I.

Nicolas Stemann, a seasoned Jelinek veteran

-- his previous productions of Das Werk (The Plant)

and Babel, both at the Vienna Burgtheater, were highly

acclaimed -- made full use of the author's invitation to "fuck

around with her." As he once stated with a spoiled son's patronizing

self-assurance, staging Jelinek's texts first requires airing

out the old lady's head.

Born in 1968 in the politicized milieu

of Meinhof's generation, Stemann was raised by a radical feminist

mother who made his eleven-year-old sister read radical feminist

literature. His mother's powerful presence might have made him

immune to nostalgia for the revolutionary spirit of the sixties,

but it did not completely wean him from directorial fathers. Many

of his images can be traced to signature devices of some of his

older colleagues -- most prominently Castorf's introduction of

the author herself onstage (reduced by Stemann to the metonymic

wig), Christoph Marthaler's inclusion of a performing pianist,

and Einar Schleef's insertion of himself into the mise-en-scène

(which Castorf and Schlingensief have done too). Though Stemann

categorically denies such appropriations, his choices are consistent

with Jelinek's processing of existing texts. She has repeatedly

declared that anger is the driving force of all her writing, and

Stemann notes that because of his biography he first perceived

her as the enemy -- an aging, if not anachronistic feminist. Once

he decided to stage Ulrike Maria Stuart, his resistance

to the material was his starting position. Thus, the play may

be about the relationship between mother and child, but Röhl was

mistaken in assuming it was about Meinhof and herself; in Stemann's

version, it is more about the director's unresolved issues with

his mother(s).

Stemann cut down the cyber-samizdat version

of the text to approximately a third of its original length, rearranging

it around key phrases woven throughout the text. Spoken by different

figures and repeated in pop songs, these phrases add up to a mnemonic

scaffolding of sorts that supports the visual and verbal overflow.

Some of these key lines are: "Killing solves

many things," "I am chairman of the board of the exploited," "All

you do is stage yourself as victim," or "One more dead is better

than one less." The mantra-like statement, "I don't know what

has to happen in order for something to happen," serves as a kind

of leitmotif. As an ironic echo from recent history, Stemann added

a well known quote from a famous 1997 speech by then German president

Roman Herzog: "A jolt must galvanize Germany." In this so-called

"jolt-speech" (Ruckrede) -- nine years after the fall

of the Berlin Wall, towards the end of Chancellor Kohl's 16-year

conservative regime when the country faced staggering unemployment

-- Herzog exhorted his reunited yet disillusioned fellow-citizens

to stop complaining and meet the challenges of the global market.

Excerpts from the speech are performed by the company with foam

coming out of their mouths: Germany's obsolete Left and new Americanized

Right meet in their disgust over the populace's resigned dependence

on the state.

Meinhof's repeated statement "I've been

dead for thirty years already" -- another directorial addition

-- highlights the pathetic obsolescence of her project. Some of

Jelinek's lines suggesting the younger generation's jealousy of

their parents' concrete enemies are turned into schmaltzy lyrics:

Oh, if only we could have experienced

the repressive ideological machineries; however, that sort of

offensive position was available only to you. We didn't have

that option. Otherwise we too could have chosen to go underground.

Stemann, who is part of that younger generation,

likes to emphasize that he is not interested at all in the Baader-Meinhof

agenda. The irretrievable loss of meaning -- his generation's

defining experience -- makes it impossible to approach the group's

misapplied idealism with any seriousness. Rather, he wanted to

explore aspects of its members' iconic features in the context

of contemporary pop culture.

The

production opens with three men in drag, women's wigs and scripts

in their hands, trying out different line-readings before the

heavy velvet theater curtain: a vaudevillian warm-up routine.

That curtain opens to reveal yet another identical red velvet

curtain, which peels off to reveal a movie screen, which gives

way to a revolving nightclub stage. Curtains behind curtains and

stages within stages highlight the theatricality behind Jelinek's

professed anti-theatrical stance, while circumscribing a space

that's sealed off from the "real world." Jelinek, a TV junkie,

emphasizes that she does not draw from "real life" but rather

from the mediatized reality she is confined to on account of her

phobias. She does not travel except between her two homes, one

in Vienna, inherited from her mother, the other in Munich, shared

with her husband. She rarely goes out. Except for close friends

and collaborators, she does not receive visitors. The performance

space thus aptly evokes her prison-house of language. Within this

setting Stemann dismantles Jelinek's complex montage into a revue

of loosely connected sketches.

The

production opens with three men in drag, women's wigs and scripts

in their hands, trying out different line-readings before the

heavy velvet theater curtain: a vaudevillian warm-up routine.

That curtain opens to reveal yet another identical red velvet

curtain, which peels off to reveal a movie screen, which gives

way to a revolving nightclub stage. Curtains behind curtains and

stages within stages highlight the theatricality behind Jelinek's

professed anti-theatrical stance, while circumscribing a space

that's sealed off from the "real world." Jelinek, a TV junkie,

emphasizes that she does not draw from "real life" but rather

from the mediatized reality she is confined to on account of her

phobias. She does not travel except between her two homes, one

in Vienna, inherited from her mother, the other in Munich, shared

with her husband. She rarely goes out. Except for close friends

and collaborators, she does not receive visitors. The performance

space thus aptly evokes her prison-house of language. Within this

setting Stemann dismantles Jelinek's complex montage into a revue

of loosely connected sketches.

The men's clowning climaxes in a ketchup-bloodied,

syrup-smeared scenario inspired by Paul McCarthy, the Utah-born

video/installation artist and Jelinek's declared favorite. (In

2005 she saw a major retrospective of his work in Munich.) Stripped

naked, their penises covered in pig's masks, the stooges distribute

water balloons and protective plastic sheets among the spectators,

inviting them to aim at signs representing former chancellor Schröder

flanked by well known business and media tycoons. Back onstage,

the actors spray each other with fake blood, chocolate shit and

miracle whip. Sliding, slipping and rolling in the mess, they

finally collapse, singing "Pigs or human"-- allegedly Holger Meins's

last words before dying from his hunger strike. Ensslin's comment

as she steps over the bodies, "I only see dead bodies the moment

I close my eyes," is greeted with laughter by the audience. The

reaction seems to validate Stemann's claim that it is no longer

possible to shock or provoke people. With the revolution fashionably

reduced to the acting out of infantile impulses, audiences happily

participate.

In

this production, Gudrun Ensslin emerges as a media-savvy pop icon

whose petty vanity causes the demise of the group. In contrast,

Meinhof's obsessive reflections lead to her hanging herself. It

was Ensslin's trying on of a sweater in an upscale Hamburg boutique

that got the police on her track. With the director's method of

looping several key phrases and weaving them throughout the performance,

the sweater incident frames her petty (bourgeois) vanity, which

not only defines her flawed revolutionary leadership but also,

by way of Jelinek's multi-referential syntax, deflates all revolutionary

stances -- including that of the author, who has repeatedly flaunted

her obsession with designer clothes in interviews and photo shoots.

In

this production, Gudrun Ensslin emerges as a media-savvy pop icon

whose petty vanity causes the demise of the group. In contrast,

Meinhof's obsessive reflections lead to her hanging herself. It

was Ensslin's trying on of a sweater in an upscale Hamburg boutique

that got the police on her track. With the director's method of

looping several key phrases and weaving them throughout the performance,

the sweater incident frames her petty (bourgeois) vanity, which

not only defines her flawed revolutionary leadership but also,

by way of Jelinek's multi-referential syntax, deflates all revolutionary

stances -- including that of the author, who has repeatedly flaunted

her obsession with designer clothes in interviews and photo shoots.

Ulrike Meinhof first appears onscreen --

larger than life, long dark hair, sunglasses projecting a fashionable,

darkly rebellious mystique purportedly for a film titled The

Downfall Part II (alluding to the Oscar-nominated 2004 film

about Adolf Hitler, starring Bruno Ganz). Parts of Meinhof's and

Ensslin's speeches and writings are performed as pop songs. The

text of Schiller's pivotal scene between Mary and Elizabeth is

projected on a screen and read by one of the stooges, while Meinhof

and Ensslin, dressed in Elizabethan costumes and playing recorders,

perform the soundtrack, as it were, of the confrontation of the

queens.

The Oedipal thrust of Stemann's project

has its coyly outrageous moments. A skit he added, titled "Vagina

Dialogues," features "Elfie" (Jelinek) and "Marlene" (Jelinek's

former protégée and friend, the Austrian writer Marlene Streeruwitz),

their heads sticking out of silky, fur-lined vaginas. Their wistful

chat about the predicament of intelligent women shunned by men

is based on a 1997 joint interview with them, originally published

in the pioneering feminist magazine Emma. The real Streeruwitz,

not as good humored as Jelinek, found her stage appearance as

a giant vagina demeaning and filed a complaint, requesting that

the scene be cut. A judge ruled that as a satire it was protected

by artistic freedom.

As usual, power and desire are closely

connected in Jelinek's scenario. The two young women, Meinhof

and Ensslin, compete as intensely for control over the group as

for Andreas Baader, who appears as a graying angel in a fashionable

black leather jacket and huge white wings, spouting invectives

against the women and ranting about the misapplication of Marxist

principles. The old rebel angel's contemporaries are two old women

with walkers -- ghostly queens, the undead of the past embodying

the younger women's unfulfilled future selves. Played by two distinguished

actresses of Jelinek's generation, Elisabeth Schwarz (Maria) and

Katharina Matz (Elizabeth), they also suggest aspects of the aging

author.

Throughout

the performance, both the script and a disheveled woman's wig

are passed around and tossed about like fetishized body parts.

Finally Stemann himself appears wearing a wig with Jelinek's trademark

pigtails. Seated with his back to the audience in his directorial

work clothes, facing a large portrait of the author as literary

diva, he reads Ulrike's lines in Jelinek's melodious, characteristically

Viennese lilt, albeit deliberately distorted by his Northern German

pronunciation. Jelinek's and Meinhof's voices merge in his performance

-- a dirge-like riff on the acknowledgment of failure and the

desire to sleep towards death.

Throughout

the performance, both the script and a disheveled woman's wig

are passed around and tossed about like fetishized body parts.

Finally Stemann himself appears wearing a wig with Jelinek's trademark

pigtails. Seated with his back to the audience in his directorial

work clothes, facing a large portrait of the author as literary

diva, he reads Ulrike's lines in Jelinek's melodious, characteristically

Viennese lilt, albeit deliberately distorted by his Northern German

pronunciation. Jelinek's and Meinhof's voices merge in his performance

-- a dirge-like riff on the acknowledgment of failure and the

desire to sleep towards death.

We set nothing in motion, I fear. I am

just a shadow, not much light left to tear up the towel and

lean the bed against the wall, but I manage, what else is left

for me to do. I am ending it now, I am preparing it all, just

for me; I have ended, I don't need a trial, and certainly not

by this group, which isn't mine . . .

Sleep well, my dear I tell myself, for

no one else is there to say so, no, not in a long time, no one

says that sort of thing to me, would have been nice, maybe,

but now I have to tell myself: sleep well, yes, sleep, sleep

even in this uncomfortable position, even in this noose, which

I may even tie myself . . . there, I go to sleep now, sleep,

sleep, I am going to sleep, so I won't have to speak anymore.

Simple as that . . . just want to sleep, sleep, sleep in the

air, in the noose, it will be beautiful . . .

What seems at first a touching, meditative

moment that captures the melancholy underlying Jelinek's rage,

is undermined by the tableau of the man in control of the text

embodying the female author, crowned by her sacrificial scalp

as trophy, in a pose of humble worship underneath her iconic photograph.

Underscored by droning techno music, with the ensemble gradually

gathering around the musicians, some actors still naked, their

bodies smeared with ketchup and syrup, others crowned with little

cotton halos, the action suggests a mock ritual led by the director/shaman.

With post-climactic calm, he embodies the author after her (body

of) text has been cut to pieces, reassembled, and taken apart

again, it's pages ultimately crumpled, torn and scattered from

above. His recital of the speech, written by a woman as the voice

of another woman, amounts to an act of cannibalism: the ingestion

and regurgitation of the body of the text.

Fittingly enough, at the opening night

curtain call Jelinek, who didn't attend, was represented by her

wig, impaled on a foot-high pole at the center of the line of

bowing actors -- an ambivalent gesture of homage to, as well as

triumph over, the author, who is reduced to a sophomoric Freudian

joke. At subsequent curtain calls, Stemann held the wig in his

hand, leaving no doubt whose show it was.

Not that Jelinek is an involuntary victim.

Through her self-deprecating stage directions she coyly flashes

her presence to her (mostly male) directors, only to withdraw

again behind impenetrable layers of language. In that sense, Stemann's

use of layers of theatrical curtains is an astute response to

her flirtatious disappearing acts. It's up to her directors to

tease narrative threads with recognizable speakers out of the

dense linguistic fabric.

The unrestricted surrender of her texts

to her trusted directors raises several conflicting issues: is

it an act of great generosity or the surrender of agency? Is the

aging author once again on the vanguard towards a new definition

of performance as text? Does her resolve to post her future writings

exclusively on her Web site challenge the commodification of authors

by their publishers? According to Jelinek, her non-interference

is not entirely a philosophical, political choice, but an existential

necessity. Her life-long fear of crowds (in conjunction with the

neurotic need of approval fostered by her relentlessly demanding

mother) intensified after the Nobel Prize.

The next production of Ulrike Maria

Stuart, staged by Jossi Wieler, another seasoned Jelinek

director, is scheduled to open March 28, 2007, at Munich's renowned

Kammerspiele, and should offer significant points of comparison.

Wieler's penetrating vision of Jelinek's world has been, in the

past, antithetical to Stemann's deconstructions. Internationally

renowned, Wieler is older than Stemann, born 1951 in Switzerland

and educated in Israel. His award-winning production of Jelinek's

Wolken.Heim at the Hamburg Schauspielhaus in 1993, followed

by Er nicht als er (He not as he -- about the

Swiss poet Robert Walser) at the 1998 Salzburg Festival introduced

a radically minimalist approach to these texts. Shaped by different

generational experiences, the two productions of Ulrike Maria

Stuart will no doubt speak to each other across the phantom

walls that divide historical memory.

Epilogue

About one month after attending the opening

of Ulrike Maria Stuart, I revisited Gerhard Richter's

cycle of paintings "October 18, 1977" at the Museum of Modern

Art in New York City. The title refers to the day the bodies of

Ensslin and Baader were found at the Stammheim prison. Richter,

born in 1932, left his native East Germany at age 29, shortly

before the Berlin Wall went up. His reworking of iconic media

images of the group leaders' demise provides interesting points

of comparison with Jelinek's approach.

Based on newspaper photographs, Richter's

paintings are deliberately opaque, individual features and contours

diffused in layers of gray: the profile of the dead Ulrike Meinhof,

her neck marked by the rope of towels with which she hanged herself;

paintings of Ensslin posing for a line-up and finally hanging

in her cell, of Baader's library and record player which he kept

in his cell, of Baader shot dead on the floor, of the infamous

arrest of the almost naked Holger Meins.

While Richter dissolves the realistic details

in grayish pigment, Jelinek wraps them in a patchwork of linguistic

ready-mades. Both interrogate memory, historic narratives and

representation. Both also try to counteract in their works the

commodification of catastrophe turned into art, even as their

own art is being commodified.

It struck me that this gallery would be

the perfect environment for a staged reading of Jelinek's difficult

play in New York City.