Bloody London:

A Report from the UK

By Caridad Svich

As the London theatre season makes West

End room for the bright new musical Billy Elliott and

a starry revival of Guys and Dolls with Ewan McGregor

and Jane Krakowski, other spaces in the city are presenting works

filled with menace and blood. At the Royal Court two new plays

are being showcased to fine advantage: David Eldridge's Incomplete

and Random Acts of Kindness and Roland Schimmelpfennig's

The Woman Before in a translation by David Tushingham.

Schimmelpfennig is a major contemporary German dramatist whose

work includes the acclaimed Arabian Night and Push

Up. While his plays are less known here in the U.S., it shouldn't

be long before they find homes at diverse American venues. His

writing--adroitly and cunningly translated by Tushingham--is witty,

stark, and mysterious.

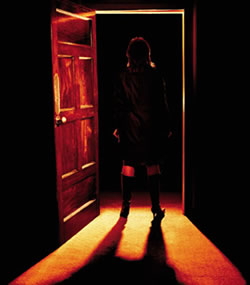

The Woman Before, staged in the

Court's downstairs space by director Richard Wilson, is a story

of love gone wrong. A seemingly happily married man receives a

knock on the door by a former girlfriend he hasn't seen in 24

years. Bewildered by her appearance, the man (played by Nigel

Lindsay) tries to make nice with this demanding and forlorn stranger

from his past (played by Helen Baxendale), but in short scenes

that go back and forth in time during a single evening, it becomes

clear that this stranger cannot be easily dissuaded from her quest

to reclaim lost love. Vengeance of a very Greek kind is on her

mind, and the play begins to spin around the escalating manipulations

of a person triumphantly ruined by her obsessive love.

Schimmelpfennig plays out the alternately

tragic and absurdly comic story, which ends with scenes of bodies

being violated and burned, in shard-like scenes of increasing

intensity. The play is structured around the clock-like machinations

and disparate perspectives of a night of violence. What starts

innocently ends tragically. Yet what distinguishes this modern

Medea-influenced tale is the macabre precision Schimmelpfennig

brings to examining every moment of the fateful night.  His

refusal to settle his characters or his audience in a zone of

comfort is strangely upsetting and fitfully frustrating. Schimmelpfennig's

goal is to unsettle and provoke, and he is abetted by a suitably

restrained, disciplined cast, which also includes Saskia Reeves

as the man's wife, Robert Pattinson as their son and Georgia Taylor

as the son's girlfriend.

His

refusal to settle his characters or his audience in a zone of

comfort is strangely upsetting and fitfully frustrating. Schimmelpfennig's

goal is to unsettle and provoke, and he is abetted by a suitably

restrained, disciplined cast, which also includes Saskia Reeves

as the man's wife, Robert Pattinson as their son and Georgia Taylor

as the son's girlfriend.

For all this, at barely 80 minutes The

Woman Before is a bit slender and lacks the transcendence

of Schimmelpfennig's Arabian Night (produced by ATC/UK

in 2002). It nevertheless confirms his unique theatrical vision.

Violence also figures prominently in productions

playing at the Royal National Theatre and the Almeida. In the

RNT's Lyttelton Theatre can be found Improbable Theatre's inspired

adaptation of the 1973 cult horror film Theatre of Blood.

At the Almeida, director Rufus Norris stages Federico Garcia Lorca's

starkly tragic Blood Wedding in a colloquial and lean

new English translation by Tanya Ronder. Both productions feature

stars--the supremely gifted stage and screen actor Jim Broadbent

as Edward Lionheart in Theatre of Blood (the role originally

played by Vincent Price in the film) and Latino movie idol Gael

Garcia Bernal as Leonardo in Blood Wedding--yet neither

relies solely on them to carry the show.

Improbable Theatre has been making magical

and inventive pieces since 1986. Led by Phelim McDermott, Julian

Crouch and Lee Simpson, it has delighted audiences with 70

Hill Lane, Lifegame, and The Hanging Man, and later

this year it will bring the show Spirit to New York Theatre

Workshop. McDermott and Crouch are also responsible, along with

Cultural Industry, for the gloriously macabre junk opera Shockheaded

Peter. Working with small- and large-scale material, Improbable

has proved over time that its name is extremely apt, a token of

the leaders' insatiable curiosity about the theater. Theatre

of Blood fits the tradition perfectly.

Drafting a full script in advance for the

first time (rather than assembling it after improvisation), McDermott

and Simpson have fashioned a faithful version of the campy film

while also creating something new. Re-setting the story in a dis-used,

derelict theatre (brilliantly designed by Rae Smith), Improbable

opens with the image of Lionheart poised upon a ladder in the

midst of a grand theatrical gesture, surrounded by ghostly figures

from different eras of theatre history. This prelude is broken

by sound and light, suddenly the figures vanish, and all that

is left is the theatre space itself and the entrance of an unassuming

yet pretentious man dandily dressed in 1970s flare trousers, black

turtleneck and sporty tweed jacket. He is, we soon discover, a

theatre critic.

So the naughtily brilliant, rough-around-the-edges

mayhem begins. For those unfamiliar with the film, the story is

blunderingly simple and deliciously obvious: a Shakespearean actor

of dubious talent is not given the Critics Award at end of the

season and kills himself, or so it seems. What transpires instead

is that he takes up with a band of the undead and vows to seek

revenge on every critic who has given him a bad notice. The revenge

takes the form of murders modeled after famous scenes of dismemberment,

gouging and stabbing from Shakespeare's tragedies and histories.

The story follows the murders (each more extreme than the next),

until no critic is left standing and everyone is bathed in blood.

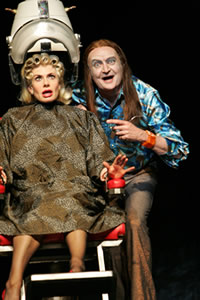

By

casting Broadbent, one of the UK's most beloved comic actors,

McDermott ensures the audience's immediate engagement. Unlike

Vincent Price, who exuded a peculiar, somewhat effete menace,

Broadbent is all size, madness, and heart. What is terrifying

about him, despite the camp, is the melancholy vulnerability that

underlies his uncontrollable, obsessive streak of serial killings.

He is an actor wronged, and a human being destroyed by a desire

for positive acknowledgment from the very critics he purports

to despise. Broadbent embraces the paradox of the role with aplomb

and finesse. His fellow players, which include the esteemed Hayley

Carmichael, Bloolips Queer Theatre co-founder Bette Bourne, classical

actor Sally Dexter and the young Rachel Stirling (who plays the

role originated by her mother Diana Rigg in the film), all deliver

impeccably grand performances as well.

By

casting Broadbent, one of the UK's most beloved comic actors,

McDermott ensures the audience's immediate engagement. Unlike

Vincent Price, who exuded a peculiar, somewhat effete menace,

Broadbent is all size, madness, and heart. What is terrifying

about him, despite the camp, is the melancholy vulnerability that

underlies his uncontrollable, obsessive streak of serial killings.

He is an actor wronged, and a human being destroyed by a desire

for positive acknowledgment from the very critics he purports

to despise. Broadbent embraces the paradox of the role with aplomb

and finesse. His fellow players, which include the esteemed Hayley

Carmichael, Bloolips Queer Theatre co-founder Bette Bourne, classical

actor Sally Dexter and the young Rachel Stirling (who plays the

role originated by her mother Diana Rigg in the film), all deliver

impeccably grand performances as well.

Part of this production's charm has to

do with the puerile adolescent's intoxicating relish at shocking

an audience and indulging in sheer gore. With all of Improbable's

pieces (and this is true of Shockheaded Peter too) the

joy of what it took to make the work in the first place is always

present. You can sense from McDermott's zealous and overextended

approach to the story of Theatre of Blood the strangely

guilty pleasure he must have had watching the cult film when he

was a child. That the piece is at the National (as a co-production

with Improbable) makes it all the more irresistible. After all,

this is where GREAT plays have been staged season after season,

not rude, prankish, super-bloody, B-horror-flick adaptations!

The incongruity of the venue is sublime, especially in light of

the piece's innumerable theatrical references. It's as if Lincoln

Center had produced, with full resources and ingenuity, a production

of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane.

At the Almeida, Rufus Norris has followed

up his Festen (a critical triumph that will likely come

to Broadway this fall) with a death-ballad staging of Garcia Lorca's

Blood Wedding. Reducing the cast to thirteen, Norris

strips the play down to a few elements: a curtain, a wooden chair,

and a harness. The movement is sparse and the pace feverish. His

multi-ethnic cast (from Iceland, Mexico, Ireland, England, Netherlands,

Portugal, the Caribbean and India) spit their lines in bursts:

thoughts half-rendered, spoken aloud. It is always night, and

the color of the sky is vaginal red. Orlando Gough's music draws

from klezmer, Celtic folk songs, samba, and cabaret. There is

no interval and the show clocks in at 90-odd minutes.

Although

Garcia Bernal is the box-office draw, he is not the production's

center. The focus is directorial, Norris's wrestling match with

this extraordinarily difficult, beautiful beast of a play. While

the lightning-speed approach is provocative--and certainly Lorca

invites Death to rule the dramatic world--I felt that Norris could

have trusted the play a bit more, let its tender and joyful side

blossom as much as its fiercely haunted fatalism. Even the wedding

scene is tinged with incessant despair, and the result is a one-sided

reading. In his attempt to wrest the piece from folkloric stereotypes

that often mar productions of Garcia Lorca's work, Norris has

gone too far in viewing the play as Thanatos's triumph over Eros

from the get-go. Nevertheless, the production demonstrates Norris's

ambition and intelligence as a director willing to go for broke

with his vision.

Although

Garcia Bernal is the box-office draw, he is not the production's

center. The focus is directorial, Norris's wrestling match with

this extraordinarily difficult, beautiful beast of a play. While

the lightning-speed approach is provocative--and certainly Lorca

invites Death to rule the dramatic world--I felt that Norris could

have trusted the play a bit more, let its tender and joyful side

blossom as much as its fiercely haunted fatalism. Even the wedding

scene is tinged with incessant despair, and the result is a one-sided

reading. In his attempt to wrest the piece from folkloric stereotypes

that often mar productions of Garcia Lorca's work, Norris has

gone too far in viewing the play as Thanatos's triumph over Eros

from the get-go. Nevertheless, the production demonstrates Norris's

ambition and intelligence as a director willing to go for broke

with his vision.

As for the performers, particular standouts

are Bjorn Haraldsson as the Groom and Rosaleen Linehan as the

Mother. Bernal is hard-working, if lacking a bit in power as the

betraying lover, but it's nice to see a star of his international

status taking a pay cut to work on a classic in a small venue

far from his native city.

Displacement and dissent mark two international

pieces--KUBA and The Story of Ronald, the Clown from

McDonald's--that live between the worlds of theatre and performance

art. The enterprising company Artangel, spearheaded by Michael

Morris, is presenting KUBA by Turkish artist Kutlag Ataman

in an abandoned sorting office just off of Bloomsbury. The area

known as Kuba emerged in Istanbul in the late 1960s as a neighborhood

of safe houses. Today it is comprised of a few hundred dwellings

that are home to non-conformists of various religions and ethnicities.

Accessed by several flights of stairs in the graffitti-marked

sorting office, the entrance to this multiple DVD installation

is a creaky institutional door that opens onto a vast room where

about twenty TV sets (different makes and models -- all old) play

edited testimonials of Kuba residents. Mostly shot in medium and

close-up, these videos tell stories of abuse, defiance and despair.

Violence

weaves the stories together -- the violence of parents on children,

gang members on passersby, brother on brother. While presented

as an art installation, KUBA functions as virtual theater

of testimony due to its complex storytelling and emphasis on the

real. It's a remarkable installation that raises important questions

about the protection of dissidents and the recording and witnessing

of their stories.

Violence

weaves the stories together -- the violence of parents on children,

gang members on passersby, brother on brother. While presented

as an art installation, KUBA functions as virtual theater

of testimony due to its complex storytelling and emphasis on the

real. It's a remarkable installation that raises important questions

about the protection of dissidents and the recording and witnessing

of their stories.

Argentine-born, Madrid-based writer-director

Rodrigo Garcia has similar storytelling matters in mind in The

Story of Ronald, the Clown from McDonald's. Garcia brought

his aptly named La Carniceria Teatro (Slaughter Theatre) to the

Brighton Festival in May for the UK premiere of this imagistic,

highly physical, assaultive meditation on consumer culture and

globalization. Performed by three actors, The Story of Ronald

brings to mind the early work of avant-gardists such as Squat

Theatre and Pina Bausch.

The piece begins with a lanky young man

standing next to a podium displaying a Big Mac, fries and a large

Coke. He tells us (in Spanish -- English subtitles appear in the

background) that his father was quite ill when he was as child.

When he was taken to the hospital to visit him, the reward awaiting

him at the end was a trip to McDonald's. The actor then calmly

strips down to his underwear and is bathed in milk by another

performer. The milk-bathing becomes more and more savage as the

young man flails about like an animal in the sloshing white mess,

barely able to breathe and yet craving more and more milk. As

the evening progresses, other stories are told in similar direct

address by each of the three actors, all broken up by movement

sections where ketchup, whipped cream, baked beans, hamburgers,

slabs of meat and soft drinks are significantly featured as their

partners in dance. Despite these brief descriptions that stress

the punk excess of Garcia's staging, this piece is exhilarating--utterly

captivating in its grossness and challenging physical presence.

Reveling in the body, in the smells of the foods we eat and discard,

in the mixture of nausea and delight with which we experience

our roles as citizens of the Americas indebted to a multi-national

few who try to govern and in fact dictate our taste, The Story

of Ronald is an elegy for a time when the likes of Simon

Cowell and Posh & Becks did not compete for attention in the same

psychic space as Borges, Cervantes and Oscar Wilde.

During my London sojourn, many practitioners

complained to me of the increasingly conservative climate in UK

theatre right now, and of the syndrome of unnecessary, starry

revivals, as ubiquitous across the pond as it is on Broadway.

Nevertheless, the evidence is clear that innovative new work and

writing continue to be valued, if not always enthusiastically

embraced, by British audiences and critics. What The Woman

Before, Theatre of Blood, Blood Wedding, KUBA and The

Story of Ronald have in common, beyond the shared thematic

concern of violence and its effects, is a fundamental belief that

art matters.